Claude Debussy |

Claude Debussy

I’m trying to find new realities… fools call it impressionism. C. Debussy

The French composer C. Debussy is often called the father of the music of the XNUMXth century. He showed that every sound, chord, tonality can be heard in a new way, can live a freer, multicolored life, as if enjoying its very sound, its gradual, mysterious dissolution in silence. Much really makes Debussy related to pictorial impressionism: the self-sufficing brilliance of elusive, fluid-moving moments, love for the landscape, airy trembling of space. It is no coincidence that Debussy is considered the main representative of impressionism in music. However, he is further than the Impressionist artists, he has gone from traditional forms, his music is directed to our century much deeper than the painting of C. Monet, O. Renoir or C. Pissarro.

Debussy believed that music is like nature in its naturalness, endless variability and diversity of forms: “Music is exactly the art that is closest to nature … Only musicians have the advantage of capturing all the poetry of night and day, earth and sky, recreating their atmosphere and rhythmically convey their immense pulsation. Both nature and music are felt by Debussy as a mystery, and above all, the mystery of birth, an unexpected, unique design of a capricious game of chance. Therefore, the composer’s skeptical and ironic attitude towards all kinds of theoretical clichés and labels in relation to artistic creativity, involuntarily schematizing the living reality of art, is understandable.

Debussy began to study music at the age of 9 and already in 1872 he entered the junior department of the Paris Conservatory. Already in the conservatory years, the unconventionality of his thinking manifested itself, which caused clashes with harmony teachers. On the other hand, the novice musician received true satisfaction in the classes of E. Guiraud (composition) and A. Mapmontel (piano).

In 1881, Debussy, as a house pianist, accompanied the Russian philanthropist N. von Meck (a great friend of P. Tchaikovsky) on a trip to Europe, and then, at her invitation, visited Russia twice (1881, 1882). Thus began Debussy’s acquaintance with Russian music, which greatly influenced the formation of his own style. “The Russians will give us new impulses to free ourselves from the absurd constraint. They … opened a window overlooking the expanse of fields. Debussy was captivated by the brilliance of timbres and subtle depiction, the picturesqueness of N. Rimsky-Korsakov’s music, the freshness of A. Borodin’s harmonies. He called M. Mussorgsky his favorite composer: “No one addressed the best that we have, with greater tenderness and greater depth. He is unique and will remain unique thanks to his art without far-fetched techniques, without withering rules. The flexibility of the vocal-speech intonation of the Russian innovator, freedom from pre-established, “administrative”, in Debussy’s words, forms were implemented in their own way by the French composer, became an integral feature of his music. “Go listen to Boris. It has the whole Pelléas,” Debussy once said about the origins of the musical language of his opera.

After graduating from the conservatory in 1884, Debussy participates in competitions for the Grand Prize of Rome, which gives the right to a four-year improvement in Rome, at the Villa Medici. During the years spent in Italy (1885-87), Debussy studied the choral music of the Renaissance (G. Palestrina, O. Lasso), and the distant past (as well as the originality of Russian music) brought a fresh stream, updated his harmonic thinking. The symphonic works sent to Paris for a report (“Zuleima”, “Spring”) did not please the conservative “masters of musical destinies”.

Returning ahead of schedule to Paris, Debussy draws closer to the circle of symbolist poets headed by S. Mallarme. The musicality of symbolist poetry, the search for mysterious connections between the life of the soul and the natural world, their mutual dissolution – all this attracted Debussy very much and largely shaped his aesthetics. It is no coincidence that the most original and perfect of the composer’s early works were romances to the words of P. Verdun, P. Bourget, P. Louis, and also C. Baudelaire. Some of them (“Wonderful Evening”, “Mandolin”) were written during the years of study at the conservatory. Symbolist poetry inspired the first mature orchestral work – the prelude “Afternoon of a Faun” (1894). In this musical illustration of Mallarmé’s eclogue, Debussy’s peculiar, subtly nuanced orchestral style developed.

The impact of symbolism was most fully felt in Debussy’s only opera Pelléas et Mélisande (1892-1902), written to the prose text of M. Maeterlinck’s drama. This is a love story, where, according to the composer, the characters “do not argue, but endure their lives and fates.” Debussy here, as it were, creatively argues with R. Wagner, the author of Tristan and Isolde, he even wanted to write his own Tristan, despite the fact that in his youth he was extremely fond of Wagner’s opera and knew it by heart. Instead of the open passion of Wagnerian music, here is the expression of a refined sound game, full of allusions and symbols. “Music exists for the inexpressible; I would like her to come out of the twilight, as it were, and in moments return to the twilight; so that she always be modest, ”wrote Debussy.

It is impossible to imagine Debussy without piano music. The composer himself was a talented pianist (as well as a conductor); “He almost always played in semitones, without any sharpness, but with such fullness and density of sound as Chopin played,” recalled the French pianist M. Long. It was from Chopin’s airiness, the spatiality of the sound of the piano fabric that Debussy repelled in his coloristic searches. But there was another source. The restraint, evenness of the emotional tone of Debussy’s music unexpectedly brought it closer to the ancient pre-romantic music – especially the French harpsichordists of the Rococo era (F. Couperin, J. F. Rameau). The ancient genres from the “Suite Bergamasco” and the Suite for Piano (Prelude, Minuet, Passpier, Sarabande, Toccata) represent a peculiar, “impressionistic” version of neoclassicism. Debussy does not resort to stylization at all, but creates his own image of early music, rather an impression of it than its “portrait”.

The composer’s favorite genre is a program suite (orchestral and piano), like a series of diverse paintings, where the static landscapes are set off by fast moving, often dance rhythms. Such are the suites for orchestra “Nocturnes” (1899), “The Sea” (1905) and “Images” (1912). For the piano, “Prints”, 2 notebooks of “Images”, “Children’s Corner”, which Debussy dedicated to his daughter, are created. In Prints, the composer for the first time tries to get used to the musical worlds of various cultures and peoples: the sound image of the East (“Pagodas”), Spain (“Evening in Grenada”) and a landscape full of movement, play of light and shadow with French folk song (“Gardens in the rain”).

In two notebooks of preludes (1910, 1913) the whole figurative world of the composer was revealed. The transparent watercolor tones of The Girl with the Flaxen Hair and The Heather are contrasted by the richness of the sound palette in The Terrace Haunted by Moonlight, in the prelude Aromas and Sounds in the Evening Air. The ancient legend comes to life in the epic sound of the Sunken Cathedral (this is where the influence of Mussorgsky and Borodin was especially pronounced!). And in the “Delphian Dancers” the composer finds a unique antique combination of the severity of the temple and the rite with pagan sensuality. In the choice of models for the musical incarnation, Debussy achieves perfect freedom. With the same subtlety, for example, he penetrates the world of Spanish music (The Alhambra Gate, The Interrupted Serenade) and recreates (using the rhythm of the cake walk) the spirit of the American minstrel theater (General Lavin the Eccentric, The Minstrels).

In the preludes, Debussy presents his entire musical world in a concise, concentrated form, generalizes it and says goodbye to it in many respects – with his former system of visual-musical correspondences. And then, in the last 5 years of his life, his music, becoming even more complicated, expands genre horizons, some kind of nervous, capricious irony begins to be felt in it. Increasing interest in stage genres. These are ballets (“Kamma”, “Games”, staged by V. Nijinsky and the troupe of S. Diaghilev in 1912, and a puppet ballet for children “Toy Box”, 1913), music for the mystery of the Italian futurist G. d’Annunzio ” Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian” (1911). The ballerina Ida Rubinshtein, choreographer M. Fokin, artist L. Bakst took part in the production of the mystery. After the creation of Pelléas, Debussy repeatedly tried to start a new opera: he was attracted by the plots of E. Poe (Devil in the Bell Tower, The Fall of the House of Escher), but these plans were not realized. The composer planned to write 6 sonatas for chamber ensembles, but managed to create 3: for cello and piano (1915), for flute, viola and harp (1915) and for violin and piano (1917). Editing the works of F. Chopin prompted Debussy to write Twelve Etudes (1915), dedicated to the memory of the great composer. Debussy created his last works when he was already terminally ill: in 1915 he underwent an operation, after which he lived for just over two years.

In some of Debussy’s compositions, the events of the First World War were reflected: in the “Heroic Lullaby”, in the song “The Nativity of Homeless Children”, in the unfinished “Ode to France”. Only the list of titles indicates that in recent years there has been an increased interest in dramatic themes and images. On the other hand, the composer’s view of the world becomes more ironic. Humor and irony have always set off and, as it were, complemented the softness of Debussy’s nature, her openness to impressions. They manifested themselves not only in music, but also in well-aimed statements about composers, in letters, and in critical articles. For 14 years Debussy was a professional music critic; the result of this work was the book “Mr. Krosh – Antidilettante” (1914).

In the post-war years, Debussy, along with such impudent destroyers of romantic aesthetics as I. Stravinsky, S. Prokofiev, P. Hindemith, was perceived by many as a representative of the impressionist yesterday. But later, and especially in our time, the colossal significance of the French innovator began to become clear, who had a direct influence on Stravinsky, B. Bartok, O. Messiaen, who anticipated the sonor technique and, in general, a new sense of musical space and time – and in this new dimension asserted humanity as the essence of art.

K. Zenkin

Life and creative path

Childhood and years of study. Claude Achille Debussy was born on August 22, 1862 in Saint-Germain, Paris. His parents – petty bourgeois – loved music, but were far from real professional art. Random musical impressions of early childhood contributed little to the artistic development of the future composer. The most striking of these were rare visits to the opera. Only at the age of nine did Debussy begin to learn to play the piano. At the insistence of a pianist close to their family, who recognized Claude’s extraordinary abilities, his parents sent him in 1873 to the Paris Conservatory. In the 70s and 80s of the XNUMXth century, this educational institution was a stronghold of the most conservative and routinist methods of teaching young musicians. After Salvador Daniel, the music commissar of the Paris Commune, who was shot during the days of its defeat, the director of the conservatory was the composer Ambroise Thomas, a man who was very limited in matters of musical education.

Among the teachers of the conservatory there were also outstanding musicians – S. Frank, L. Delibes, E. Giro. To the best of their ability, they supported every new phenomenon in the musical life of Paris, every original performing and composing talent.

The diligent studies of the first years brought Debussy annual solfeggio awards. In the solfeggio and accompaniment classes (practical exercises for the piano in harmony), for the first time, his interest in new harmonic turns, various and complex rhythms manifested itself. The colorful and coloristic possibilities of the harmonic language open up before him.

Debussy’s pianistic talent developed extremely rapidly. Already in his student years, his playing was distinguished by its inner content, emotionality, subtlety of nuance, rare variety and richness of the sound palette. But the originality of his performing style, devoid of fashionable external virtuosity and brilliance, did not find due recognition either among the teachers of the conservatory or among Debussy’s peers. For the first time, his pianistic talent was awarded a prize only in 1877 for the performance of Schumann’s sonata.

The first serious clashes with the existing methods of conservatory teaching occur with Debussy in the harmony class. Independent harmonic thinking of Debussy could not put up with the traditional restrictions that reigned in the course of harmony. Only the composer E. Guiraud, with whom Debussy studied composition, truly imbued with the aspirations of his student and found unanimity with him in artistic and aesthetic views and musical tastes.

Already the first vocal compositions of Debussy, dating back to the late 70s and early 80s (“Wonderful Evening” to the words of Paul Bourget and especially “Mandolin” to the words of Paul Verlaine), revealed the originality of his talent.

Even before graduating from the conservatory, Debussy undertook his first foreign trip to Western Europe at the invitation of the Russian philanthropist N. F. von Meck, who for many years belonged to the number of close friends of P. I. Tchaikovsky. In 1881 Debussy came to Russia as a pianist to take part in von Meck’s home concerts. This first trip to Russia (then he went there two more times – in 1882 and 1913) aroused the composer’s great interest in Russian music, which did not weaken until the end of his life.

Since 1883, Debussy began to participate as a composer in competitions for the Grand Prize of Rome. The following year he was awarded it for the cantata The Prodigal Son. This work, which in many ways still bears the influence of French lyric opera, stands out for the real drama of individual scenes (for example, Leah’s aria). Debussy’s stay in Italy (1885-1887) turned out to be fruitful for him: he got acquainted with the ancient choral Italian music of the XNUMXth century (Palestrina) and at the same time with the work of Wagner (in particular, with the musical drama “Tristan and Isolde”).

At the same time, the period of Debussy’s stay in Italy was marked by a sharp clash with the official artistic circles of France. The reports of the laureates before the academy were presented in the form of works that were considered in Paris by a special jury. Reviews of the composer’s works – the symphonic ode “Zuleima”, the symphonic suite “Spring” and the cantata “The Chosen One” (written already on arrival in Paris) – this time discovered an insurmountable gulf between Debussy’s innovative aspirations and the inertia that reigned in the largest art institution France. The composer was accused of a deliberate desire to “do something strange, incomprehensible, impracticable”, of “an exaggerated sense of musical color”, which makes him forget “the importance of accurate drawing and form”. Debussy was accused of using “closed” human voices and the key of F-sharp major, allegedly inadmissible in a symphonic work. The only fair, perhaps, was the remark about the absence of “flat turns and banality” in his works.

All the compositions sent by Debussy to Paris were still far from the mature style of the composer, but they already showed innovative features, which manifested themselves primarily in the colorful harmonic language and orchestration. Debussy clearly expressed his desire for innovation in a letter to one of his friends in Paris: “I can’t close my music in too correct frames … I want to work to create an original work, and not fall all the time on the same paths …”. Upon his return from Italy to Paris, Debussy finally breaks with the academy.

90s. The first flowering of creativity. The desire to get close to new trends in art, the desire to expand their connections and acquaintances in the art world led Debussy back in the late 80s to the salon of a major French poet of the late 80th century and the ideological leader of the Symbolists – Stefan Mallarmé. On “Tuesdays” Mallarme gathered outstanding writers, poets, artists – representatives of the most diverse trends in modern French art (poets Paul Verlaine, Pierre Louis, Henri de Regnier, artist James Whistler and others). Here Debussy met writers and poets, whose works formed the basis of many of his vocal compositions, created in the 90-50s. Among them stand out: “Mandolin”, “Ariettes”, “Belgian landscapes”, “Watercolors”, “Moonlight” to the words of Paul Verlaine, “Songs of Bilitis” to the words of Pierre Louis, “Five Poems” to the words of the greatest French poet 60— Charles Baudelaire’s XNUMXs (especially “Balcony”, “Evening Harmonies”, “At the Fountain”) and others.

Even a simple list of the titles of these works makes it possible to judge the composer’s predilection for literary texts, which contained mainly landscape motifs or love lyrics. This sphere of poetic musical images becomes a favorite for Debussy throughout his career.

The clear preference given to vocal music in the first period of his work is explained to a large extent by the composer’s passion for Symbolist poetry. In the verses of the symbolist poets, Debussy was attracted by subjects close to him and new artistic techniques – the ability to speak laconicly, the absence of rhetoric and pathos, the abundance of colorful figurative comparisons, a new attitude to rhyme, in which musical combinations of words are caught. Such a side of symbolism as the desire to convey a state of gloomy foreboding, fear of the unknown, never captured Debussy.

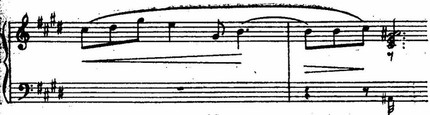

In most of the works of these years, Debussy tries to avoid both symbolist uncertainty and understatement in the expression of his thoughts. The reason for this is loyalty to the democratic traditions of national French music, the whole and healthy artistic nature of the composer (it is no coincidence that he most often refers to Verlaine’s poems, which intricately combine the poetic traditions of the old masters, with their desire for clear thought and simplicity of style, with the refinement inherent in art of contemporary aristocratic salons). In his early vocal compositions, Debussy strives to embody such musical images that retain connection with existing musical genres – song, dance. But this connection often appears, as in Verlaine, in a somewhat exquisitely refined refraction. Such is the romance “Mandolin” to the words of Verlaine. In the melody of the romance, we hear the intonations of French urban songs from the repertoire of the “chansonnier”, which are performed without accentuated accents, as if “singing”. The piano accompaniment conveys a characteristic jerky, plucked-like sound of a mandolin or guitar. The chord combinations of “empty” fifths resemble the sound of the open strings of these instruments:

Already in this work, Debussy uses some of the coloristic techniques typical of his mature style in harmony – “series” of unresolved consonances, an original comparison of major triads and their inversions in distant keys,

The 90s were the first period of Debussy’s creative flourishing in the field of not only vocal, but also piano music (“Suite Bergamas”, “Little Suite” for piano four hands), chamber-instrumental (string quartet) and especially symphonic music (in this time, two of the most significant symphonic works are created – the prelude “Afternoon of a Faun” and “Nocturnes”).

The prelude “Afternoon of a Faun” was written on the basis of a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé in 1892. Mallarme’s work attracted the composer primarily by the bright picturesqueness of a mythological creature dreaming on a hot day about beautiful nymphs.

In the prelude, as in Mallarmé’s poem, there is no developed plot, no dynamic development of the action. At the heart of the composition lies, in essence, one melodic image of “languor”, built on “creeping” chromatic intonations. Debussy uses for his orchestral incarnation almost all the time the same specific instrumental timbre – a flute in a low register:

The entire symphonic development of the prelude comes down to varying the texture of the presentation of the theme and its orchestration. The static development is justified by the nature of the image itself.

The composition of the work is three-part. Only in a small middle part of the prelude, when a new diatonic theme is carried out by the string group of the orchestra, does the general character become more intense, expressive (the dynamics reaches its maximum sonority in the prelude ff, the only time the tutti of the entire orchestra is used). The reprise ends with the gradually disappearing, as it were, dissolving theme of “languor”.

The features of Debussy’s mature style appeared in this work primarily in the orchestration. The extreme differentiation of orchestra groups and parts of individual instruments within groups makes it possible to combine and combine orchestral colors in a variety of ways and allows you to achieve the finest nuances. Many of the achievements of orchestral writing in this work later became typical of most of Debussy’s symphonic works.

Only after the performance of “Faun” in 1894 did Debussy the composer speak in the wider musical circles of Paris. But the isolation and certain limitations of the artistic environment to which Debussy belonged, as well as the original individuality of the style of his compositions, prevented the composer’s music from appearing on the concert stage.

Even such an outstanding symphonic work by Debussy as the Nocturnes cycle, created in 1897-1899, met with a restrained attitude. In “Nocturnes” Debussy’s intensified desire for life-real artistic images was manifested. For the first time in Debussy’s symphonic work, a lively genre painting (the second part of the Nocturnes – “Festivities”) and images of nature rich in colors (the first part – “Clouds”) received a vivid musical embodiment.

During the 90s, Debussy worked on his only completed opera, Pelléas et Mélisande. The composer was looking for a plot close to him for a long time (He started and abandoned work on the opera “Rodrigo and Jimena” based on Corneille’s tragedy “Sid”. The work remained unfinished, since Debussy hated (in his own words) “the imposition of action”, its dynamic development, emphasized affective expression of feelings, boldly outlined literary images of heroes.) and finally settled on the drama of the Belgian symbolist writer Maurice Maeterlinck “Pelléas et Mélisande”. There is very little external action in this work, its place and time hardly change. All the author’s attention is focused on the transfer of the subtlest psychological nuances in the experiences of the characters: Golo, his wife Mélisande, Golo’s brother Pelléas6. The plot of this work attracted Debussy, in his words, by the fact that in it “the characters do not argue, but endure life and fate.” The abundance of subtext, thoughts, as it were, “to oneself” made it possible for the composer to realize his motto: “Music begins where the word is powerless.”

Debussy retained in the opera one of the main features of many of Maeterlinck’s dramas – the fatal doom of the characters before the inevitable fatal denouement, a person’s disbelief in his own happiness. In this work of Maeterlinck, the social and aesthetic views of a significant part of the bourgeois intelligentsia at the turn of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries were vividly embodied. Romain Rolland gave a very accurate historical and social assessment of the drama in his book “Musicians of Our Days”: “The atmosphere in which Maeterlinck’s drama develops is a tired humility that gives the will to live into the power of Rock. Nothing can change the order of events. […] No one is responsible for what he wants, for what he loves. […] They live and die without knowing why. This fatalism, reflecting the fatigue of the spiritual aristocracy of Europe, was miraculously conveyed by Debussy’s music, which added to it its own poetry and sensual charm … “. Debussy, to a certain extent, managed to soften the hopelessly pessimistic tone of the drama with subtle and restrained lyricism, sincerity and truthfulness in the musical embodiment of the real tragedy of love and jealousy.

The stylistic novelty of the opera is largely due to the fact that it was written in prose. The vocal parts of Debussy’s opera contain subtle shades and nuances of colloquial French speech. The melodic development of the opera is a gradual (without jumps at long intervals), but expressive melodious-declamatory line. The abundance of caesuras, exceptionally flexible rhythm and frequent changes in performing intonation allow the composer to accurately and aptly convey the meaning of almost every prose phrase with music. Any significant emotional upsurge in the melodic line is absent even in the dramatic climactic episodes of the opera. At the moment of the highest tension of action, Debussy remains true to his principle – maximum restraint and the complete absence of external manifestations of feelings. Thus, the scene of Pelléas declaring his love to Melisande, contrary to all operatic traditions, is performed without any affectation, as if in a “half-whisper”. The scene of Mélisande’s death is solved in the same way. There are a number of scenes in the opera where Debussy managed to convey with surprisingly subtle means a complex and rich range of various shades of human experiences: the scene with the ring by the fountain in the second act, the scene with Mélisande’s hair in the third, the scene at the fountain in the fourth and the scene of Mélisande’s death in the fifth act.

The opera was staged on April 30, 1902 at the Comic Opera. Despite the magnificent performance, the opera did not have real success with a wide audience. Criticism was generally unfriendly and allowed itself sharp and rude attacks after the first performances. Only a few major musicians have appreciated the merits of this work.

After staging Pelléas, Debussy made several attempts to compose operas different in genre and style from the first. Libretto was written for two operas based on fairy tales based on Edgar Allan Poe – The Death of the House of Escher and The Devil in the Bell Tower – sketches were made, which the composer himself destroyed shortly before his death. Also, Debussy’s intention to create an opera based on the plot of Shakespeare’s tragedy King Lear was not realized. Having abandoned the artistic principles of Pelléas et Mélisande, Debussy was never able to find himself in other operatic genres closer to the traditions of French classical opera and theater dramaturgy.

1900-1918 – the peak of Debussy’s creative flowering. Musical-critical activity. Shortly before the production of Pelléas, a significant event took place in Debussy’s life – from 1901 he became a professional music critic. This new activity for him proceeded intermittently in 1901, 1903 and 1912-1914. The most significant articles and statements of Debussy were collected by him in 1914 in the book “Mr. Krosh is an anti-amateur”. Critical activity contributed to the formation of Debussy’s aesthetic views, his artistic criteria. It allows us to judge the composer’s very progressive views on the tasks of art in the artistic formation of people, on his attitude to classical and modern art. At the same time, it is not without some one-sidedness and inconsistency in the assessment of various phenomena and in aesthetic judgments.

Debussy ardently opposes the prejudice, ignorance and dilettantism that dominate contemporary criticism. But Debussy also objects to an exclusively formal, technical analysis when evaluating a musical work. He defends as the main quality and dignity of criticism – the transmission of “sincere, truthful and heartfelt impressions.” The main task of Debussy’s criticism is the fight against the “academism” of the official institutions of France at that time. He places sharp and caustic, largely fair remarks about the Grand Opera, where “the best wishes are smashed against a strong and indestructible wall of stubborn formalism that does not allow any kind of bright ray to penetrate.”

His aesthetic principles and views are extremely clearly expressed in Debussy’s articles and book. One of the most important is the composer’s objective attitude to the world around him. He sees the source of music in nature: “Music is closest to nature …”. “Only musicians have the privilege of embracing the poetry of night and day, earth and sky – recreating the atmosphere and rhythm of the majestic trembling of nature.” These words undoubtedly reveal a certain one-sidedness of the composer’s aesthetic views on the exclusive role of music among other forms of art.

At the same time, Debussy argued that art should not be confined to a narrow circle of ideas accessible to a limited number of listeners: “The task of the composer is not to entertain a handful of “enlightened” music lovers or specialists.” Surprisingly timely were Debussy’s statements about the degradation of national traditions in French art at the beginning of the XNUMXth century: “One can only regret that French music has followed paths that treacherously led it away from such distinctive qualities of the French character as clarity of expression, precision and composure of form.” At the same time, Debussy was against national limitations in art: “I am well acquainted with the theory of free exchange in art and I know what valuable results it has led to.” His ardent propaganda of Russian musical art in France is the best proof of this theory.

The work of major Russian composers – Borodin, Balakirev, and especially Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov – was deeply studied by Debussy back in the 90s and had a certain influence on some aspects of his style. Debussy was most impressed by the brilliance and colorful picturesqueness of Rimsky-Korsakov’s orchestral writing. “Nothing can convey the charm of the themes and the dazzle of the orchestra,” wrote Debussy about Rimsky-Korsakov’s Antar symphony. In Debussy’s symphonic works, there are orchestration techniques close to Rimsky-Korsakov, in particular, a predilection for “pure” timbres, a special characteristic use of individual instruments, etc.

In Mussorgsky’s songs and the opera Boris Godunov, Debussy appreciated the deep psychological nature of music, its ability to convey all the richness of a person’s spiritual world. “No one has yet turned to the best in us, to more tender and deep feelings,” we find in the composer’s statements. Subsequently, in a number of Debussy’s vocal compositions and in the opera Pelléas et Mélisande, one can feel the influence of Mussorgsky’s extremely expressive and flexible melodic language, which conveys the subtlest shades of living human speech with the help of melodic recitative.

But Debussy perceived only certain aspects of the style and method of the greatest Russian artists. He was alien to the democratic and social accusatory tendencies in Mussorgsky’s work. Debussy was far from the deeply humane and philosophically significant plots of Rimsky-Korsakov’s operas, from the constant and inseparable connection between the work of these composers and folk origins.

Features of internal inconsistency and some one-sidedness in Debussy’s critical activity were manifested in his obvious underestimation of the historical role and artistic significance of the work of such composers as Handel, Gluck, Schubert, Schumann.

In his critical remarks, Debussy sometimes took idealistic positions, arguing that “music is a mysterious mathematics, the elements of which are involved in infinity.”

Speaking in a number of articles in support of the idea of creating a folk theater, Debussy almost simultaneously expresses the paradoxical idea that “high art is the destiny of only the spiritual aristocracy.” This combination of democratic views and well-known aristocracy was very typical of the French artistic intelligentsia at the turn of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries.

The 1900s are the highest stage in the creative activity of the composer. The works created by Debussy during this period speak of new trends in creativity and, first of all, Debussy’s departure from the aesthetics of symbolism. More and more the composer is attracted by genre scenes, musical portraits and pictures of nature. Along with new themes and plots, features of a new style appear in his work. Evidence of this are such piano works as “An Evening in Grenada” (1902), “Gardens in the Rain” (1902), “Island of Joy” (1904). In these compositions, Debussy finds a strong connection with the national origins of music (in “An Evening in Grenada” – with Spanish folklore), preserves the genre basis of music in a kind of refraction of dance. In them, the composer further expands the scope of the timbre-colorful and technical capabilities of the piano. He uses the finest gradations of dynamic hues within a single sound layer or juxtaposes sharp dynamic contrasts. Rhythm in these compositions begins to play an increasingly expressive role in creating an artistic image. Sometimes it becomes flexible, free, almost improvisational. At the same time, in the works of these years, Debussy reveals a new desire for a clear and strict rhythmic organization of the compositional whole by repeatedly repeating one rhythmic “core” throughout the entire work or its large section (prelude in A minor, “Gardens in the Rain”, “Evening in Grenada”, where the rhythm of the habanera is the “core” of the entire composition).

The works of this period are distinguished by a surprisingly full-blooded perception of life, boldly outlined, almost visually perceived, images enclosed in a harmonious form. The “impressionism” of these works is only in the heightened sense of color, in the use of colorful harmonic “glare and spots”, in the subtle play of timbres. But this technique does not violate the integrity of the musical perception of the image. It only gives it more bulge.

Among the symphonic works created by Debussy in the 900s, the “Sea” (1903-1905) and “Images” (1909) stand out, which includes the famous “Iberia”.

The suite “Sea” consists of three parts: “On the sea from dawn to noon”, “The play of the waves” and “The conversation of the wind with the sea”. The images of the sea have always attracted the attention of composers of various trends and national schools. Numerous examples of programmatic symphonic works on “marine” themes by Western European composers can be cited (the overture “Fingal’s Cave” by Mendelssohn, symphonic episodes from “The Flying Dutchman” by Wagner, etc.). But the images of the sea were most vividly and fully realized in Russian music, especially in Rimsky-Korsakov (the symphonic picture Sadko, the opera of the same name, the Scheherazade suite, the intermission to the second act of the opera The Tale of Tsar Saltan),

Unlike Rimsky-Korsakov’s orchestral works, Debussy sets in his work not plot, but only pictorial and coloristic tasks. He seeks to convey by means of music the change of light effects and colors on the sea at different times of the day, the different states of the sea – calm, agitated and stormy. In the composer’s perception of the paintings of the sea, there are absolutely no such motives that could give a twilight mystery to their coloring. Debussy is dominated by bright sunlight, full-blooded colors. The composer boldly uses both dance rhythms and broad epic picturesqueness to convey relief musical images.

In the first part, a picture of the slowly-calm awakening of the sea at dawn, the lazily rolling waves, the glare of the first sunbeams on them unfolds. The orchestral beginning of this movement is especially colorful, where, against the background of the “rustle” of the timpani, the “drip” octaves of two harps and the “frozen” tremolo violins in the high register, short melodic phrases from the oboe appear like the glare of the sun on the waves. The appearance of a dance rhythm does not break the charm of complete peace and dreamy contemplation.

The most dynamic part of the work is the third – “The Conversation of the Wind with the Sea”. From the motionless, frozen picture of a calm sea at the beginning of the part, reminiscent of the first, a picture of a storm unfolds. Debussy uses all musical means for dynamic and intense development – melodic-rhythmic, dynamic and especially orchestral.

At the beginning of the movement, brief motifs are heard that take place in the form of a dialogue between cellos with double basses and two oboes against the background of the muffled sonority of the bass drum, timpani and tom-tom. In addition to the gradual connection of new groups of the orchestra and a uniform increase in sonority, Debussy uses the principle of rhythmic development here: introducing more and more new dance rhythms, he saturates the fabric of the work with a flexible combination of several rhythmic patterns.

The end of the whole composition is perceived not only as a revelry of the sea element, but as an enthusiastic hymn to the sea, the sun.

Much in the figurative structure of the “Sea”, the principles of orchestration, prepared the appearance of the symphonic piece “Iberia” – one of the most significant and original works of Debussy. It strikes with its closest connection with the life of the Spanish people, their song and dance culture. In the 900s, Debussy turned several times to topics related to Spain: “An Evening in Grenada”, the preludes “Gate of the Alhambra” and “The Interrupted Serenade”. But “Iberia” is among the best works of composers who drew from the inexhaustible spring of Spanish folk music (Glinka in “Aragonese Jota” and “Nights in Madrid”, Rimsky-Korsakov in “Spanish Capriccio”, Bizet in “Carmen”, Ravel in ” Bolero” and a trio, not to mention the Spanish composers de Falla and Albeniz).

“Iberia” consists of three parts: “On the streets and roads of Spain”, “Fragrances of the night” and “Morning of the holiday”. The second part reveals Debussy’s favorite pictorial paintings of nature, imbued with a special, spicy aroma of the Spanish night, “written” with the composer’s subtle pictorialism, a quick change of flickering and disappearing images. The first and third parts paint pictures of the people’s life in Spain. Particularly colorful is the third part, which contains a large number of various song and dance Spanish melodies, which create a lively picture of a colorful folk holiday by quickly changing each other. The greatest Spanish composer de Falla said this about Iberia: “The echo of the village in the form of the main motive of the whole work (“Sevillana”) seems to flutter in the clear air or in the trembling light. The intoxicating magic of the Andalusian nights, the liveliness of the festive crowd, which is dancing to the sounds of the chords of the “gang” of guitarists and bandurists … – all this is in a whirlwind in the air, now approaching, then receding, and our constantly waking imagination is blinded by the mighty virtues of intensely expressive music with its rich nuances.”

The last decade in Debussy’s life is distinguished by incessant creative and performing activity until the outbreak of the First World War. Concert trips as a conductor to Austria-Hungary brought the composer fame abroad. He was especially warmly received in Russia in 1913. Concerts in St. Petersburg and Moscow were a great success. Debussy’s personal contact with many Russian musicians further strengthened his attachment to Russian musical culture.

The beginning of the war caused Debussy to rise in patriotic feelings. In printed statements, he emphatically calls himself: “Claude Debussy is a French musician.” A number of works of these years are inspired by the patriotic theme: “Heroic Lullaby”, the song “Christmas of Homeless Children”; in the suite for two pianos “White and Black” Debussy wanted to convey his impressions of the horrors of the imperialist war. Ode to France and the cantata Joan of Arc remained unrealized.

In the work of Debussy in recent years, one can find a variety of genres that he had not encountered before. In chamber vocal music, Debussy finds an affinity for the old French poetry of Francois Villon, Charles of Orleans and others. With these poets, he wants to find a source of renewal of the subject and at the same time pay tribute to the old French art that he has always loved. In the field of chamber instrumental music, Debussy conceives a cycle of six sonatas for various instruments. Unfortunately, he managed to write only three – a sonata for cello and piano (1915), a sonata for flute, harp and viola (1915) and a sonata for violin and piano (1916-1917). In these compositions, Debussy adheres to the principles of suite composition rather than sonata composition, thereby reviving the traditions of French composers of the XNUMXth century. At the same time, these compositions testify to the incessant search for new artistic techniques, colorful color combinations of instruments (in the sonata for flute, harp and viola).

Particularly great are the artistic achievements of Debussy in the last decade of his life in piano work: “Children’s Corner” (1906-1908), “Toy Box” (1910), twenty-four preludes (1910 and 1913), “Six Antique Epigraphs” in four hands ( 1914), twelve studies (1915).

The piano suite “Children’s Corner” is dedicated to Debussy’s daughter. The desire to reveal the world in music through the eyes of a child in his usual images – a strict teacher, a doll, a little shepherd, a toy elephant – makes Debussy widely use both everyday dance and song genres, and genres of professional music in a grotesque, caricatured form – a lullaby in “The Elephant’s Lullaby ”, a shepherd’s tune in “The Little Shepherd”, a cake-walk dance that was fashionable at that time, in the play of the same name. Next to them, a typical study in “Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum” allows Debussy to create the image of a pedant-teacher and a bored student by means of soft caricature.

Debussy’s twelve etudes are connected with his long-term experiments in the field of piano style, the search for new types of piano technique and means of expression. But even in these works, he strives to solve not only purely virtuoso, but also sound problems (the tenth etude is called: “For contrasting sonorities”). Unfortunately, not all of Debussy’s sketches were able to embody the artistic concept. Some of them are dominated by a constructive principle.

Two notebooks of his preludes for piano should be considered a worthy conclusion to the whole creative path of Debussy. Here, as it were, the most characteristic and typical aspects of the artistic worldview, creative method and style of the composer were concentrated. The cycle contains the full range of the figurative and poetic sphere of Debussy’s work.

Until the last days of his life (he died on March 26, 1918 during the bombing of Paris by the Germans), despite a serious illness, Debussy did not stop his creative search. He finds new themes and plots, turning to traditional genres, and refracts them in a peculiar way. All these searches never develop in Debussy into an end in itself – “the new for the sake of the new.” In works and critical statements of recent years about the work of other contemporary composers, he tirelessly opposes the lack of content, intricacies of form, deliberate complexity of the musical language, characteristic of many representatives of the modernist art of Western Europe in the late XNUMXth and early XNUMXth centuries. He rightly remarked: “As a general rule, any intention to complicate form and feeling shows that the author has nothing to say.” “Music becomes difficult every time it’s not there.” The lively and creative mind of the composer tirelessly seeks connections with life through musical genres that are not stifled by dry academicism and decadent sophistication. These aspirations did not receive real continuation from Debussy due to a certain ideological limitation of the bourgeois environment in this crisis era, due to the narrowness of creative interests, characteristic even of such major artists as he himself was.

B. Ionin

- Piano works of Debussy →

- Symphonic works of Debussy →

- French musical impressionism →

Compositions:

operas – Rodrigue and Jimena (1891-92, did not end), Pelléas and Mélisande (lyrical drama after M. Maeterlinck, 1893-1902, staged in 1902, Opera Comic, Paris); ballets – Games (Jeux, lib. V. Nijinsky, 1912, post. 1913, tr Champs Elysees, Paris), Kamma (Khamma, 1912, piano score; orchestrated by Ch. Kouklen, final performance 1924, Paris), Toy Box (La boîte à joujoux, children’s ballet, 1913, arranged for 2 fp., orchestrated by A. Caplet, c. 1923); for soloists, choir and orchestra – Daniel (cantata, 1880-84), Spring (Printemps, 1882), Call (Invocation, 1883; preserved piano and vocal parts), Prodigal Son (L’enfant prodigue, lyrical scene, 1884), Diana in the forest (cantata, based on the heroic comedy by T. de Banville, 1884-1886, not finished), The Chosen One (La damoiselle élue, lyric poem, based on the plot of the poem by the English poet D. G. Rossetti, French translation by G. Sarrazin, 1887-88), Ode to France (Ode à la France, cantata, 1916-17, not finished, after Debussy’s death the sketches were completed and printed by M. F. Gaillard); for orchestra – The Triumph of Bacchus (divertimento, 1882), Intermezzo (1882), Spring (Printemps, symphonic suite at 2 o’clock, 1887; re-orchestrated according to the instructions of Debussy, French composer and conductor A. Busset, 1907), Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun (Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, based on the eclogue of the same name by S. Mallarme, 1892-94), Nocturnes: Clouds, Festivities, Sirens (Nocturnes: Nuages, Fêtes; Sirènes, with women’s choir; 1897-99 ), The Sea (La mer, 3 symphonic sketches, 1903-05), Images: Gigues (orchestration completed by Caplet), Iberia, Spring Dances (Images: Gigues, Ibéria, Rondes de printemps, 1906-12); for instrument and orchestra — Suite for cello (Intermezzo, c. 1880-84), Fantasia for piano (1889-90), Rhapsody for saxophone (1903-05, unfinished, completed by J. J. Roger-Ducas, publ. 1919), Dances (for harp with string orchestra, 1904), First Rhapsody for clarinet (1909-10, originally for clarinet and piano); chamber instrumental ensembles – piano trio (G-dur, 1880), string quartet (g-moll, op. 10, 1893), sonata for flute, viola and harp (1915), sonata for cello and piano (d-moll, 1915), sonata for violin and piano (g-moll, 1916); for piano 2 hands – Gypsy dance (Danse bohémienne, 1880), Two arabesques (1888), Bergamas suite (1890-1905), Dreams (Rêverie), Ballad (Ballade slave), Dance (Styrian tarantella), Romantic waltz, Nocturne, Mazurka (all 6 plays – 1890), Suite (1901), Prints (1903), Island of Joy (L’isle joyeuse, 1904), Masks (Masques, 1904), Images (Images, 1st series, 1905; 2nd series, 1907 ), Children’s Corner (Children’s corner, piano suite, 1906-08), Twenty-Four Preludes (1st notebook, 1910; 2nd notebook, 1910-13), Heroic lullaby (Berceuse héroïque, 1914; orchestral edition, 1914 ), Twelve Studies (1915) and others; for piano 4 hands – Divertimento and Andante cantabile (c. 1880), symphony (h-moll, 1 hour, 1880, found and published in Moscow, 1933), Little Suite (1889), Scottish March on a Folk Theme (Marche écossaise sur un thème populaire, 1891, also transcribed for symphonic orchestra by Debussy), Six Antique Epigraphs (Six épigraphes antiques, 1914), etc.; for 2 pianos 4 hands – Lindaraja (Lindaraja, 1901), On white and black (En blanc et noir, suite of 3 pieces, 1915); for flute – Pan’s flute (Syrinx, 1912); for a cappella choir – Three songs of Charles d’Orleans (1898-1908); for voice and piano – Songs and romances (lyrics by T. de Banville, P. Bourget, A. Musset, M. Bouchor, c. 1876), Three romances (lyrics by L. de Lisle, 1880-84), Five poems by Baudelaire (1887- 89), Forgotten ariettes (Ariettes oubliées, lyrics by P. Verlaine, 1886-88), Two romances (words by Bourget, 1891), Three melodies (words by Verlaine, 1891), Lyric prose (Proses lyriques, lyrics by D. , 1892-93), Songs of Bilitis (Chansons de Bilitis, lyrics by P. Louis, 1897), Three Songs of France (Trois chansons de France, lyrics by C. Orleans and T. Hermite, 1904), Three ballads on the lyrics. F. Villon (1910), Three poems by S. Mallarmé (1913), Christmas of children who no longer have shelter (Noël des enfants qui n’ont plus de maison, lyrics by Debussy, 1915), etc.; music for drama theater performances – King Lear (sketches and sketches, 1897-99), The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian (music for the oratorio-mystery of the same name by G. D’Annunzio, 1911); transcriptions – works by K. V. Gluck, R. Schumann, C. Saint-Saens, R. Wagner, E. Satie, P. I. Tchaikovsky (3 dances from the ballet “Swan Lake”), etc.