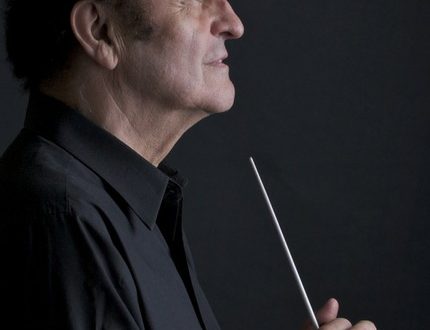

Christoph Eschenbach |

Christopher Eschenbach

Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of the Washington National Symphony Orchestra and the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Christoph Eschenbach is a permanent collaborator with the world’s most renowned orchestras and opera houses. A student of George Sell and Herbert von Karajan, Eschenbach led such ensembles as the Orchester de Paris (2000-2010), the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra (2003-2008), the North German Radio Symphony Orchestra (1994-2004), the Houston Symphony Orchestra (1988) -1999), Tonhalle Orchestra; was artistic director of music festivals in Ravinia and Schleswig-Holstein.

The 2016/17 season is the maestro’s seventh and final season at the NSO and the Kennedy Center. During this time, the orchestra under his leadership made three major tours, which were a huge success: in 2012 – in South and North America; in 2013 – in Europe and Oman; in 2016 – again in Europe. In addition, Christoph Eschenbach and the orchestra regularly perform at Carnegie Hall. This season’s events include the premiere of the U.Marsalis Violin Concerto on the US East Coast, a work commissioned by the NSO, as well as the final concert of the Exploring Mahler program.

Christoph Eschenbach’s current engagements include a new production of B. Britten’s opera The Turn of the Screw at Milan’s La Scala, performances as a guest conductor with the Orchester de Paris, the National Orchestra of Spain, the Seoul and London Philharmonic Orchestras, the Philharmonic Orchestra of Radio Netherlands, the National Orchestra of France, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra of Stockholm.

Kristof Eschenbach has an extensive discography as a pianist and conductor, collaborating with a number of well-known recording companies. Among the recordings with NSO is the album “Remembering John F. Kennedy” by Ondine. On the same label, recordings were made with the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Orchestre de Paris; with the latter an album was also released on Deutsche Grammophon; The conductor has recorded with the London Philharmonic on EMI/LPO Live, with the London Symphony on DG/BM, the Vienna Philharmonic on Decca, the North German Radio Symphony and the Houston Symphony on Koch.

Many of the maestro’s works in the field of sound recording have received a number of prestigious awards, including the Grammy in 2014; nominations “Disc of the Month” according to BBC magazine, “Editor’s Choice” according to Gramophon magazine, as well as an award from the German Association of Music Critics. A disc of compositions by Kaia Saariaho with the Orchestra de Paris and soprano Karita Mattila in 2009 won the award of the professional jury of Europe’s largest music fair MIDEM (Marché International du Disque et de l’Edition Musicale). In addition, Christoph Eschenbach recorded a complete cycle of H. Mahler’s symphonies with the Orchestra de Paris, which are freely available on the musician’s website.

The merits of Christoph Eschenbach are marked by prestigious awards and titles in many countries of the world. Maestro – Chevalier of the Order of the Legion of Honor, Commander of the Order of Arts and Fine Letters of France, the Grand Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit for the Federal Republic of Germany and the National Order of the Federal Republic of Germany; winner of the L. Bernstein Prize awarded by the Pacific Music Festival, whose artistic director K. Eschenbach was in the 90s. In 2015 he was awarded the Ernst von Siemens Prize, which is called the “Nobel Prize” in the field of music.

Maestro devotes a lot of time to teaching; regularly gives master classes at the Manhattan School of Music, the Kronberg Academy and at the Schleswig-Holstein Festival, often collaborates with the youth orchestra of the festival. In rehearsals with the NSO in Washington, Eschenbach allows student fellows to take part in rehearsals on an equal footing with the musicians of the orchestra.

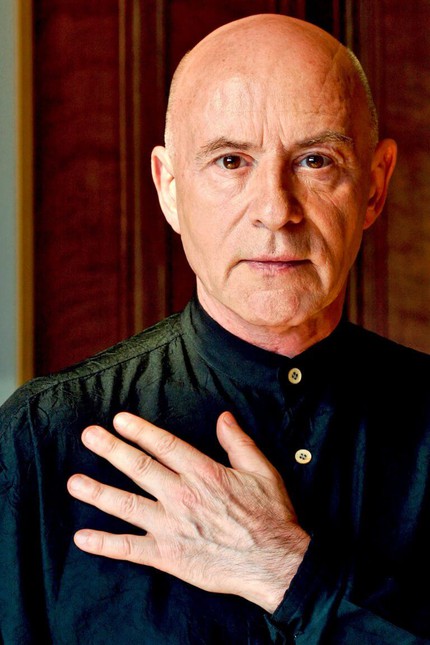

During the first post-war years in West Germany, there was a clear lag in pianistic art. For many reasons (the legacy of the past, the shortcomings of musical education, and just a coincidence), German pianists almost never took high places in international competitions, did not enter the big concert stage. That is why from the moment when it became known about the appearance of a brightly gifted boy, the eyes of music lovers rushed to him with hope. And, as it turned out, not in vain.

Conductor Eugen Jochum discovered him at the age of 10, after the boy had been studying for five years under the guidance of his mother, pianist and singer Vallidor Eschenbach. Jochum referred him to the Hamburg teacher Elise Hansen. Eschenbach’s further ascent was swift, but, fortunately, this did not interfere with his systematic creative growth and did not make him a child prodigy. At the age of 11, he became the first in a competition for young musicians organized by the Stenway company in Hamburg; at the age of 13, he performed above the program at the Munich International Competition and was awarded a special prize; at 19 he received another prize – at the competition for students of music universities in Germany. All this time, Eschenbach continued to study – first in Hamburg, then at the Cologne Higher School of Music with X. Schmidt, then again in Hamburg with E. Hansen, but not privately, but at the Higher School of Music (1959-1964).

The beginning of his professional career brought Eschenbach two high awards that compensated for the patience of his compatriots – the second prize in the Munich International Competition (1962) and the Clara Haskil Prize – the only award for the winner of the competition named after her in Lucerne (1965).

Such was the starting capital of the artist – quite impressive. Listeners paid tribute to his musicality, devotion to art, technical completeness of the game. Eschenbach’s first two discs – Mozart’s compositions and Schubert’s “Trout Quintet” (with the “Kekkert Quartet”) were received favorably by critics. “Those who listen to his performance of Mozart,” we read in the magazine “Music,” inevitably get the impression that a personality appears here, perhaps called from the heights of our time to rediscover the piano works of the great master. We do not yet know where his chosen path will lead him – to Bach, Beethoven or Brahms, to Schumann, Ravel or Bartok. But the fact remains that he demonstrates not only an extraordinary spiritual receptivity (although it is this, perhaps, that will give him later the opportunity to connect polar opposites), but also an ardent spirituality.

The talent of the young pianist quickly matured and was formed extremely early: one can argue, referring to the opinions of authoritative experts, that already a decade and a half ago his appearance was not much different from today. Is that a variety of repertoire. Gradually, all those layers of piano literature about which “Muzika” wrote about are drawn into the orbit of the pianist’s attention. Sonatas by Beethoven, Schubert, Liszt are increasingly heard in his concerts. Recordings of Bartók’s plays, Schumann’s piano works, Schumann’s and Brahms’ quintets, Beethoven’s concertos and sonatas, Haydn’s sonatas, and finally, the complete collection of Mozart’s sonatas on seven records, as well as most of the piano duets of Mozart and Schubert, recorded by him with the pianist, are released one after another. Justus Franz. In concert performances and recordings, the artist constantly proves both his musicality and his growing versatility. Assessing his interpretation of Beethoven’s most difficult Hammerklavier sonata (Op. 106), reviewers especially note the rejection of everything external, of accepted traditions in tempo, ritardando and other techniques, “which are not in the notes and which pianists themselves usually use to ensure their success at the public.” Critic X. Krelman emphasizes, speaking of his interpretation of Mozart, that “Eschenbach plays based on a solid spiritual foundation that he created for himself and which became the basis for serious and responsible work for him.”

Along with the classics, the artist is also attracted by modern music, and contemporary composers are attracted by his talent. Some of them are prominent West German craftsmen G. Bialas and H.-W. Henze, dedicated piano concertos to Eschenbach, the first performer of which he became.

Although the concert activity of Eschenbach, who is strict with himself, is not as intense as that of some of his colleagues, he has already performed in most countries of Europe and America, including the USA. In 1968, the artist participated for the first time in the Prague Spring festival. The Soviet critic V. Timokhin, who listened to him, gives the following characterization of Eschenbach: “He is, of course, a gifted musician, endowed with a rich creative imagination, capable of creating his own musical world and living a tense and intense life in the circle of his images. Nevertheless, it seems to me that Eschenbach is more of a chamber pianist. He leaves the greatest impression in works fanned with lyrical contemplation and poetic beauty. But the pianist’s remarkable ability to create his own musical world makes us, if not in everything, agree with him, then with unflagging interest, follow how he realizes his original ideas, how he forms his concepts. This, in my opinion, is the reason for the great success that Eschenbach enjoys with his listeners.

As we can see, in the above statements almost nothing is said about Eschenbach’s technique, and if they mention individual techniques, it is only in connection with how they contribute to the embodiment of his concepts. This does not mean that technique is the weak side of the artist, but rather should be perceived as the highest praise for his art. However, the art is still far from perfect. The main thing that he still lacks is the scale of concepts, the intensity of experience, so characteristic of the greatest German pianists of the past. And if earlier many predicted Eschenbach as the successor of Backhaus and Kempf, now such forecasts can be heard much less frequently. But remember that both of them also experienced periods of stagnation, were subjected to rather sharp criticism and became real maestro only at a very respectable age.

There was, however, one circumstance that could prevent Eschenbach from rising to a new level in his pianism. This circumstance is a passion for conducting, which he, according to him, dreamed of since childhood. He made his debut as a conductor when he was still studying in Hamburg: he then led a student production of Hindemith’s opera We Build a City. After 10 years, the artist for the first time stood behind the console of a professional orchestra and conducted the performance of Bruckner’s Third Symphony. Since then, the share of conducting performances in his busy schedule has steadily increased and reached about 80 percent by the beginning of the 80s. Now Eschenbach very rarely plays the piano, but he remained known for his interpretations of the music of Mozart and Schubert, as well as duet performances with Zimon Barto.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya., 1990