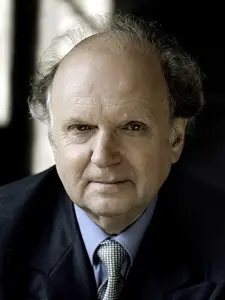

Carlo Maria Giulini |

Carlo Maria Giulini

It was a long and glorious life. Full of triumphs, an expression of gratitude from grateful listeners, but also a continuous study of the scores, the utmost spiritual concentration. Carlo Maria Giulini lived for over ninety years.

The formation of Giulini as a musician, without exaggeration, “embraces” the whole of Italy: the beautiful peninsula, as you know, is long and narrow. He was born in Barletta, a small town in the southern region of Puglia (boot heel) on May 9, 1914. But from an early age, his life was connected with the “extreme” Italian north: at the age of five, the future conductor began to study the violin in Bolzano. Now it is Italy, then it was Austria-Hungary. Then he moved to Rome, where he continued his studies at the Academy of Santa Cecilia, learning to play the viola. At the age of eighteen he became an artist of the Augusteum Orchestra, a magnificent Roman concert hall. As an orchestra member of the Augusteum, he had the opportunity – and happiness – to play with such conductors as Wilhelm Furtwängler, Erich Kleiber, Victor De Sabata, Antonio Guarnieri, Otto Klemperer, Bruno Walter. He even played under the baton of Igor Stravinsky and Richard Strauss. At the same time he studied conducting with Bernardo Molinari. He received his diploma at a difficult time, at the height of the Second World War, in 1941. His debut was delayed: he was able to stand behind the console only three years later, in 1944. He was entrusted with nothing less than the first concert in liberated Rome.

Giulini said: “Lessons in conducting require slowness, caution, loneliness and silence.” Fate fully rewarded him for the seriousness of his attitude to his art, for the lack of vanity. In 1950, Giulini moved to Milan: his entire subsequent life would be connected with the northern capital. A year later, De Sabata invited him to the Italian Radio and Television and to the Milan Conservatory. Thanks to the same De Sabate, the doors of the La Scala theater opened before the young conductor. When a heart crisis overtook De Sabata in September 1953, Giulini succeeded him as music director. He was entrusted with the opening of the season (with Catalani’s opera Valli). Giulini will remain as musical director of the Milanese temple of the opera until 1955.

Giulini is equally famous as an opera and symphony conductor, but his activity in the first capacity covers a relatively short period of time. In 1968 he would leave opera and return to it only occasionally in the recording studio and in Los Angeles in 1982 when he would conduct Verdi’s Falstaff. Although his opera production is small, he remains one of the protagonists of twentieth-century musical interpretation: suffice it to recall De Falla’s A Short Life and The Italian Girl in Algiers. Hearing Giulini, it is clear where the accuracy and transparency of Claudio Abbado’s interpretations come from.

Giulini conducted many of Verdi’s operas, paid great attention to Russian music, and loved eighteenth-century authors. It was he who conducted The Barber of Seville, performed in 1954 on Milan television. Maria Callas obeyed his magic wand (in the famous La Traviata directed by Luchino Visconti). The great director and the great conductor met at the productions of Don Carlos at Covent Ganden and The Marriage of Figaro in Rome. Operas conducted by Giulini include Monteverdi’s Coronation of Poppea, Gluck’s Alcesta, Weber’s The Free Gunner, Cilea’s Adrienne Lecouvreur, Stravinsky’s The Marriage, and Bartók’s Castle of Duke Bluebeard. His interests were incredibly broad, his symphonic repertoire is truly incomprehensible, his creative life is long and eventful.

Giulini conducted at the La Scala until 1997 – thirteen operas, one ballet and fifty concerts. Since 1968, he was attracted mainly by symphonic music. All the orchestras in Europe and America wanted to play with him. His American debut was in 1955 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. From 1976 to 1984, Giulini was the permanent conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. In Europe he was Principal Conductor of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra from 1973 to 1976 and, in addition, he played with all other famous orchestras.

Those who saw Giulini at the control panel say that his gesture was elementary, almost rude. The maestro did not belong to the exhibitionists, who love themselves much more in music than music in themselves. He said: “Music on paper is dead. Our task is nothing more than to try to revive this flawless mathematics of signs. Giulini considered himself a devoted servant of the author of music: “To interpret is an act of deep modesty towards the composer.”

Numerous triumphs never turned his head. In the last years of his career, the Parisian public gave Giulini a standing ovation for a quarter of an hour for Verdi’s Requiem, to which the Maestro remarked only: “I am very glad that I can give a little love through music.”

Carlo Maria Giulini died in Brescia on June 14, 2005. Shortly before his death, Simon Rattle said, “How can I conduct Brahms after Giulini has conducted him”?