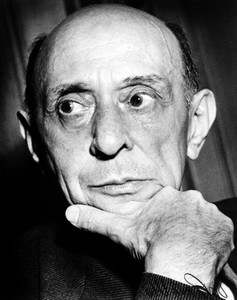

Arnold Schoenberg |

Arnold Schoenberg

All the darkness and guilt of the world the new music took upon itself. All her happiness lies in knowing misfortune; its whole beauty lies in giving up the appearance of beauty. T. Adorno

A. Schoenberg entered the history of music of the XNUMXth century. as the creator of the dodecaphone system of composition. But the significance and scale of the activity of the Austrian master are not limited to this fact. Schoenberg was a multi-talented person. He was a brilliant teacher who brought up a whole galaxy of contemporary musicians, including such well-known masters as A. Webern and A. Berg (together with their teacher, they formed the so-called Novovensk school). He was an interesting painter, a friend of O. Kokoschka; his paintings repeatedly appeared at exhibitions and were printed in reproductions in the Munich magazine “The Blue Rider” next to the works of P. Cezanne, A. Matisse, V. Van Gogh, B. Kandinsky, P. Picasso. Schoenberg was a writer, poet and prose writer, the author of the texts of many of his works. But above all, he was a composer who left a significant legacy, a composer who went through a very difficult, but honest and uncompromising path.

Schoenberg’s work is closely connected with musical expressionism. It is marked by the tension of feelings and the sharpness of the reaction to the world around us, which characterized many contemporary artists who worked in an atmosphere of anxiety, anticipation and accomplishment of terrible social cataclysms (Schoenberg was united with them by a common life fate – wandering, disorder, the prospect of living and dying far from their homeland ). Perhaps the closest analogy to Schoenberg’s personality is the compatriot and contemporary of the composer, the Austrian writer F. Kafka. Just as in Kafka’s novels and short stories, in Schoenberg’s music, a heightened perception of life sometimes condenses to feverish obsessions, sophisticated lyrics border on the grotesque, turning into a mental nightmare in reality.

Creating his difficult and deeply suffered art, Schoenberg was firm in his convictions to the point of fanaticism. All his life he followed the path of greatest resistance, struggling with ridicule, bullying, deaf misunderstanding, enduring insults, bitter need. “In Vienna in 1908 – the city of operettas, classics and pompous romanticism – Schoenberg swam against the current,” wrote G. Eisler. It was not quite the usual conflict between the innovative artist and the philistine environment. It is not enough to say that Schoenberg was an innovator who made it a rule to say in art only what had not been said before him. According to some researchers of his work, the new appeared here in an extremely specific, condensed version, in the form of a kind of essence. An over-concentrated impressionability, which requires an adequate quality from the listener, explains the particular difficulty of Schoenberg’s music for perception: even against the background of his radical contemporaries, Schoenberg is the most “difficult” composer. But this does not negate the value of his art, subjectively honest and serious, rebelling against the vulgar sweetness and lightweight tinsel.

Schoenberg combined the capacity for strong feeling with a ruthlessly disciplined intellect. He owes this combination to a turning point. The milestones of the composer’s life path reflect a consistent aspiration from traditional romantic statements in the spirit of R. Wagner (instrumental compositions “Enlightened Night”, “Pelleas and Mélisande”, cantata “Songs of Gurre”) to a new, strictly verified creative method. However, Schoenberg’s romantic pedigree also affected later, giving an impulse to increased excitement, hypertrophied expressiveness of his works at the turn of 1900-10. Such, for example, is the monodrama Waiting (1909, a monologue of a woman who came to the forest to meet her lover and found him dead).

The post-romantic cult of the mask, refined affectation in the style of “tragic cabaret” can be felt in the melodrama “Moon Pierrot” (1912) for a female voice and instrumental ensemble. In this work, Schoenberg first embodied the principle of the so-called speech singing (Sprechgesang): although the solo part is fixed in the score with notes, its pitch structure is approximate – as in a recitation. Both “Waiting” and “Lunar Pierrot” are written in an atonal manner, corresponding to a new, extraordinary warehouse of images. But the difference between the works is also significant: the orchestra-ensemble with its sparse, but differentially expressive colors from now on attracts the composer more than the full orchestral composition of the late Romantic type.

However, the next and decisive step towards strictly economical writing was the creation of a twelve-tone (dodecaphone) composition system. Schoenberg’s instrumental compositions of the 20s and 40s, such as the Piano Suite, Variations for Orchestra, Concertos, String Quartets, are based on a series of 12 non-repeating sounds, taken in four main versions (a technique dating back to the old polyphonic variation ).

The dodecaphonic method of composition has gained a lot of admirers. Evidence of the resonance of Schoenberg’s invention in the cultural world was T. Mann’s “quoting” of it in the novel “Doctor Faustus”; it also speaks of the danger of “intellectual coldness” that lies in wait for a composer who uses a similar manner of creativity. This method did not become universal and self-sufficient – even for its creator. More precisely, it was such only insofar as it did not interfere with the manifestation of the master’s natural intuition and the accumulated musical and auditory experience, sometimes entailing – contrary to all the “theories of avoidance” – diverse associations with tonal music. The composer’s parting with the tonal tradition was not irrevocable at all: the well-known maxim of the “late” Schoenberg that much more can be said in C major fully confirms this. Immersed in the problems of composing technique, Schoenberg at the same time was far from armchair isolation.

The events of the Second World War – the suffering and death of millions of people, the hatred of peoples for fascism – echoed in it with very significant composer ideas. Thus, “Ode to Napoleon” (1942, on the verse by J. Byron) is an angry pamphlet against tyrannical power, the work is filled with murderous sarcasm. The text of the cantata Survivor from Warsaw (1947), perhaps Schoenberg’s most famous work, reproduces the true story of one of the few people who survived the tragedy of the Warsaw ghetto. The work conveys the horror and despair of the last days of the ghetto prisoners, ending with an old prayer. Both works are brightly publicistic and are perceived as documents of the era. But the journalistic sharpness of the statement did not overshadow the composer’s natural inclination to philosophizing, to the problems of transtemporal sound, which he developed with the help of mythological plots. Interest in the poetics and symbolism of the biblical myth emerged as early as the 30s, in connection with the project of the oratorio “Jacob’s Ladder”.

Then Schoenberg began to work on an even more monumental work, to which he devoted all the last years of his life (however, without completing it). We are talking about the opera “Moses and Aaron”. The mythological basis served for the composer only as a pretext for reflection on topical issues of our time. The main motive of this “drama of ideas” is the individual and the people, the idea and its perception by the masses. The continuous verbal duel of Moses and Aaron depicted in the opera is the eternal conflict between the “thinker” and the “doer”, between the prophet-truth seeker trying to lead his people out of slavery, and the orator-demagogue who, in his attempt to make the idea figuratively visible and accessible essentially betrays it (the collapse of the idea is accompanied by a riot of elemental forces, embodied with amazing brightness by the author in the orgiastic “Dance of the Golden Calf”). The irreconcilability of the heroes’ positions is emphasized musically: the operatic beautiful part of Aaron contrasts with the ascetic and declamatory part of Moses, which is alien to traditional operatic singing. The oratorio is widely represented in the work. The choral episodes of the opera, with their monumental polyphonic graphics, go back to Bach’s Passions. Here, Schoenberg’s deep connection with the tradition of Austro-German music is revealed. This connection, as well as Schoenberg’s inheritance of the spiritual experience of European culture as a whole, emerges more and more clearly over time. Here is the source of an objective assessment of Schoenberg’s work and the hope that the “difficult” art of the composer will find access to the widest possible range of listeners.

T. Left

- List of major works by Schoenberg →