Andrey Gavrilov |

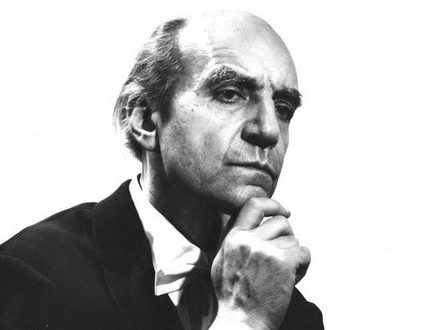

Andrei Gavrilov

Andrei Vladimirovich Gavrilov was born on September 21, 1955 in Moscow. His father was a famous artist; mother – a pianist, who studied at one time with G. G. Neuhaus. “I was taught music from the age of 4,” says Gavrilov. “But in general, as far as I remember, in my childhood it was more interesting for me to mess with pencils and paints. Isn’t it paradoxical: I dreamed of becoming a painter, my brother – a musician. And it turned out just the opposite…”

Since 1960, Gavrilov has been studying at the Central Music School. From now on and for many years, T. E. Kestner (who educated N. Petrov and a number of other famous pianists) becomes his teacher in his specialty. “It was then, at school, that a real love for the piano came to me,” Gavrilov continues to recall. “Tatyana Evgenievna, a musician of rare talent and experience, taught me a strictly verified pedagogical course. In her class, she always paid great attention to the formation of professional and technical skills in future pianists. For me, as for others, it has been of great benefit in the long run. If I didn’t have any serious difficulties with the “technique” later, thanks, first of all, to my school teacher. I remember that Tatyana Evgenievna did a lot to instill in me a love for the music of Bach and other ancient masters; this also did not go unnoticed. And how skillfully and accurately Tatyana Evgenievna compiled the educational and pedagogical repertoire! Each work in the programs selected by her turned out to be the same, almost the only one that was required at this stage for the development of her student … “

Being in the 9th grade of the Central Music School, Gavrilov made his first foreign tour, performing in Yugoslavia at the anniversary celebrations of the Belgrade music school “Stankovic”. In the same year, he was invited to take part in one of the symphony evenings of the Gorky Philharmonic; he played Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto in Gorky and, judging by the surviving testimonies, quite successfully.

Since 1973, Gavrilov has been a student at the Moscow State Conservatory. His new mentor is Professor L.N. Naumov. “Lev Nikolayevich’s teaching style turned out to be in many ways the opposite of what I was used to in Tatyana Evgenievna’s class,” says Gavrilov. “After a strict, classically balanced, at times, perhaps somewhat constrained performing arts. Of course, this greatly fascinated me … ”During this period, the creative image of the young artist is intensively formed. And, as it often happens in his youth, along with undeniable, clearly visible advantages, some debatable moments, disproportions, are also felt in his game – what is commonly called “growth costs”. Sometimes in Gavrilov the performer, a “violence of temperament” is manifested – as he himself later defines this property of his; sometimes, critical remarks are made to him about the exaggerated expression of his music-making, excessively naked emotionality, too exalted stage manners. For all that, however, none of his creative “opponents” denies that he is highly capable of captivate, inflame listening audience – but isn’t this the first and main sign of artistic talent?

In 1974, an 18-year-old youth participated in the Fifth International Tchaikovsky Competition. And he achieves a major, truly outstanding success – the first prize. Of the numerous responses to this event, it is interesting to quote the words of E. V. Malinin. Occupying at that time the post of dean of the piano faculty of the conservatory, Malinin knew Gavrilov perfectly – his pluses and minuses, used and unused creative resources. “I have great sympathy,” he wrote, “I treat this young man, primarily because he is really very talented. Impressive spontaneity, the brightness of his game is supported by first-class technical apparatus. To be precise, there are no technical difficulties for him. He now faces another task – to learn to control himself. If he succeeds in this task (and I hope that in time he will), then his prospects seem extremely bright to me. In terms of the scale of his talent – both musical and pianistic, in terms of some kind of very kind warmth, in terms of his attitude to the instrument (so far mainly to the sound of the piano), he has reason to further stand on a par with our largest performers. Nevertheless, of course, he must understand that the award of the first prize to him is to some extent an advance, a look into the future. (Modern pianists. S. 123.).

Once after the competitive triumph on the big stage, Gavrilov immediately finds himself captured by the intense rhythm of the philharmonic life. This gives a lot to a young performer. Knowledge of the laws of the professional scene, experience of live touring work, firstly. The versatile repertoire, now systematically replenished by him (more on this will be discussed later), secondly. There is, finally, a third: the wide popularity that comes to him both at home and abroad; he successfully performs in many countries, prominent Western European reviewers devote sympathetic responses to his clavirabends in the press

At the same time, the stage not only gives, but also takes away; Gavrilov, like his other colleagues, soon becomes convinced of this truth. “Lately, I’m starting to feel that long tours are exhausting me. It happens that you have to perform up to twenty, or even twenty-five times in a month (not counting records) – this is very difficult. Moreover, I can’t play full-time; every time, as they say, I give all my best without a trace … And then, of course, something similar to emptiness rises. Now I’m trying to limit my tours. True, it’s not easy. For a variety of reasons. In many ways, probably because I, in spite of everything, really love concerts. For me, this is happiness that cannot be compared with anything else … “

Looking back at the creative biography of Gavrilov in recent years, it should be noted that he was truly lucky in one respect. Not with a competitive medal – not talking about it; at competitions of musicians, fate always favors someone, not someone; this is well known and customary. Gavrilov was lucky in another way: fate gave him a meeting with Svyatoslav Teofilovich Richter. And not in the form of one or two random, fleeting dates, as in others. It so happened that Richter noticed the young musician, brought him closer to him, was passionately carried away by Gavrilov’s talent, and took a lively part in it.

Gavrilov himself calls the creative rapprochement with Richter “a stage of great importance” in his life. “I consider Svyatoslav Teofilovich my third Teacher. Although, strictly speaking, he never taught me anything – in the traditional interpretation of this term. Most often it happened that he simply sat down at the piano and began to play: I, perched nearby, looked with all my eyes, listened, pondered, memorized – it is difficult to imagine the best school for a performer. And how much conversations with Richter give me about painting, cinema or music, about people and life … I often get the feeling that near Svyatoslav Teofilovich you find yourself in some kind of mysterious “magnetic field”. Are you charging with creative currents, or something. And when after that you sit down at the instrument, you start playing with a special inspiration.”

In addition to the above, we can recall that during the Olympics-80, Muscovites and guests of the capital had a chance to witness a very unusual event in the practice of musical performance. In the picturesque museum-estate “Arkhangelskoye”, not far from Moscow, Richter and Gavrilov gave a cycle of four concerts, at which 16 Handel’s harpsichord suites (arranged for piano) were performed. When Richter sat down at the piano, Gavrilov turned the notes to him: it was the turn of the young artist to play – the illustrious master “assisted” him. To the question – how did the idea of the cycle come about? Richter replied: “I did not play Handel and therefore decided that it would be interesting to learn it. And Andrew is also helpful. So we performed all the suites ” (Zemel I. An example of genuine mentoring // Sov. music. 1981. No 1. P. 82.). The performances of the pianists had not only a great public resonance, which is easily explained in this case; accompanied them with outstanding success. “… Gavrilov,” the music press noted, “played so worthily and convincingly that he did not give the slightest reason to doubt the legitimacy of both the very idea of uXNUMXbuXNUMXbthe cycle, and the viability of the new commonwealth” (Ibid.).

If you look at other programs of Gavrilov, then today you can see different authors in them. He often turns to musical antiquity, the love for which was instilled in him by T. E. Kestner. Thus, Gavrilov’s themed evenings dedicated to Bach’s clavier concertos did not go unnoticed (the pianist was accompanied by a chamber ensemble conducted by Yuri Nikolaevsky). He willingly plays Mozart (Sonata in A major), Beethoven (Sonata in C-sharp minor, “Moonlight”). The artist’s romantic repertoire looks impressive: Schumann (Carnival, Butterflies, Carnival of Vienna), Chopin (24 studies), Liszt (Campanella) and much more. I must say that in this area, perhaps, it is easiest for him to reveal himself, to assert his artistic “I”: the magnificent, brightly colorful virtuosity of the romantic warehouse has always been close to him as a performer. Gavrilov also had many achievements in Russian, Soviet and Western European music of the XNUMXth century. We can name in this connection his interpretations of Balakirev’s Islamey, Variations in F major and Tchaikovsky’s Concerto in B flat minor, Scriabin’s Eighth Sonata, Rachmaninoff’s Third Concerto, Delusion, pieces from the Romeo and Juliet cycle and Prokofiev’s Eighth Sonata, Concerto for the left hand and “Night Gaspard” by Ravel, four pieces by Berg for clarinet and piano (together with clarinetist A. Kamyshev), vocal works by Britten (with singer A. Ablaberdiyeva). Gavrilov says that he made it a rule to replenish his repertoire every year with four new programs – solo, symphonic, chamber-instrumental.

If he does not deviate from this principle, in time his creative asset will turn out to be a really huge number of the most diverse works.

* * *

In the mid-eighties, Gavrilov performed mainly abroad for quite a long time. Then he reappears on the concert stages of Moscow, Leningrad and other cities of the country. Music lovers get the opportunity to meet him and appreciate what is called a “fresh look” – after the interval – his playing. The pianist’s performances attract the attention of critics and are subjected to more or less detailed analysis in the press. The review that appeared during this period on the pages of the magazine Musical Life is indicative – it followed Gavrilov’s clavirabend, where works by Schumann, Schubert and some other composers were performed. “Contrasts of one concerto” – this is how its author titled the review. It is easy to feel in it that reaction to Gavrilov’s playing, that attitude towards him and his art, which is generally typical today for professionals and the competent part of the audience. The reviewer generally positively evaluates the performance of the pianist. However, he states, “the impression of the clavirabend remained ambiguous.” For, “along with real musical revelations that take us into the holy of holies of music, there were moments here that were largely” external “, which lacked artistic depth.” On the one hand, the review points out, “the ability to think holistically,” on the other hand, the insufficient elaboration of the material, as a result of which, “far from all the subtleties … were felt and“ listened to ”as the music requires … some important details slipped away, remained unnoticed” (Kolesnikov N. Contrasts of one concert // Musical life. 1987. No 19. P. 8.).

The same heterogeneous and contradictory sensations arose from Gavrilov’s interpretation of Tchaikovsky’s famous B flat minor concerto (second half of the XNUMXs). Much here undoubtedly succeeded the pianist. The pomposity of the performing manner, the magnificent sound “Empire”, the convexly outlined “close-ups” – all this made a bright, winning impression. (And what were the dizzying octave effects in the first and third parts of the concert worth, which plunged the most impressionable part of the audience into rapture!) At the same time, Gavrilov’s playing, frankly speaking, lacked undisguised virtuoso bravado, and “self-show”, and noticeable sins in part taste and measure.

I remember the concert of Gavrilov, which took place in the Great Hall of the Conservatory in 1968 (Chopin, Rachmaninov, Bach, Scarlatti). I recall, further, the pianist’s joint performance with the London Orchestra conducted by V. Ashkenazy (1989, Rachmaninov’s Second Concerto). And again everything is the same. Moments of deeply expressive music-making are interspersed with frank eccentricity, tunes, harsh and noisy bravado. The main thing is the artistic thought that does not keep up with the rapidly running fingers …

… Gavrilov the concert performer has many ardent admirers. They are easy to understand. Who will argue, the musicality here is really rare: excellent intuition; the ability to lively, youthfully passionately and directly respond to the beautiful in music, unspent during the time of intensive concert performance. And, of course, captivating artistry. Gavrilov, as the public sees him, is absolutely confident in himself – this is a big plus. He has an open, sociable stage character, an “open” talent is another plus. Finally, it is also important that he is internally relaxed on stage, holding himself freely and unconstrainedly (at times, perhaps even too freely and unconstrainedly …). To be loved by the listeners – the mass audience – this is more than enough.

At the same time, I would like to hope that the artist’s talent will sparkle with new facets over time. That a great inner depth, seriousness, psychological weight of interpretations will come to him. That technicalism will become more elegant and refined, professional culture will become more noticeable, stage manners will be nobler and stricter. And that, while remaining himself, Gavrilov, as an artist, will not remain unchanged – tomorrow he will be in something different than today.

For this is the property of every great, truly significant talent – to move away from its “today”, from what has already been found, achieved, tested – to move towards the unknown and undiscovered …

G. Tsypin, 1990