Analysis of a work based on musical literature

In the last article we talked about how to disassemble plays before bringing them to work in a specialty class. The link to this material is located at the end of this post. Today our focus will also be on the analysis of a piece of music, but we will only be preparing for the lessons of musical literature.

In the last article we talked about how to disassemble plays before bringing them to work in a specialty class. The link to this material is located at the end of this post. Today our focus will also be on the analysis of a piece of music, but we will only be preparing for the lessons of musical literature.

First, let’s highlight some general fundamental points, and then consider the features of analyzing certain types of musical works – for example, opera, symphony, vocal cycle, etc.

So, every time we analyze a piece of music, we must prepare answers to at least the following points:

- the exact full title of the musical work (plus here: is there a program in the form of a title or literary explanation?);

- names of the authors of the music (there may be one composer, or there may be several if the composition is collective);

- names of the authors of the texts (in operas, several people often work on the libretto at once, sometimes the composer himself can be the author of the text);

- in what musical genre is the work written (is it opera or ballet, or symphony, or what?);

- the place of this work in the scale of the composer’s entire work (does the author have other works in the same genre, and how does the work in question relate to these others – maybe it is innovative or is it the pinnacle of creativity?);

- whether this composition is based on any non-musical primary source (for example, it was written based on the plot of a book, poem, painting, or inspired by any historical events, etc.);

- how many parts are in the work and how each part is constructed;

- performing composition (for which instruments or voices it was written – for orchestra, for ensemble, for solo clarinet, for voice and piano, etc.);

- main musical images (or characters, heroes) and their themes (musical, of course).

Now let’s move on to the features that relate to the analysis of musical works of certain types. In order not to spread ourselves too thin, we will focus on two cases – opera and symphony.

Features of opera analysis

Opera is a theatrical work, and therefore it largely obeys the laws of the theatrical stage. An opera almost always has a plot, and at least a minimal amount of dramatic action (sometimes not minimal, but very decent). The opera is staged as a performance in which there are characters; the performance itself is divided into actions, pictures and scenes.

So, here are some things to consider when analyzing an operatic composition:

- the connection between the opera libretto and the literary source (if there is one) – sometimes they differ, and quite strongly, and sometimes the text of the source is included in the opera unchanged in its entirety or in fragments;

- division into actions and pictures (the number of both), the presence of such parts as a prologue or epilogue;

- the structure of each act – traditional operatic forms predominate (arias, duets, choruses, etc.), as numbers following one another, or acts and scenes represent end-to-end scenes, which, in principle, cannot be divided into separate numbers;

- the characters and their singing voices – you just need to know this;

- how the images of the main characters are revealed – where, in what actions and pictures they participate and what they sing, how they are depicted musically;

- the dramatic basis of the opera – where and how the plot begins, what are the stages of development, in what action and how does the denouement occur;

- orchestral numbers of the opera – is there an overture or introduction, as well as intermissions, intermezzos and other orchestral purely instrumental episodes – what role do they play (often these are musical pictures that introduce the action – for example, a musical landscape, a holiday picture, a soldier’s or funeral march and etc.);

- what role does the chorus play in the opera (for example, does it comment on the action or appears only as a means of showing the everyday way of life, or the chorus artists pronounce their important lines that greatly influence the overall outcome of the action, or the chorus constantly praises something, or choral scenes in general in no opera, etc.);

- whether there are dance numbers in the opera – in what actions and what is the reason for the introduction of ballet into the opera;

- Are there leitmotifs in opera – what are they and what do they characterize (some hero, some object, some feeling or state, some natural phenomenon or something else?).

This is not a complete list of what needs to be found out in order for the analysis of a musical work in this case to be complete. Where do you get the answers to all these questions? First of all, in the clavier of the opera, that is, in its musical text. Secondly, you can read a brief summary of the opera libretto, and, thirdly, you can simply learn a lot in books – read textbooks on musical literature!

Features of symphony analysis

In some ways, a symphony is easier to understand than an opera. Here there is much less musical material (the opera lasts 2-3 hours, and the symphony 20-50 minutes), and there are no characters with their numerous leitmotifs, which you still need to try to distinguish from each other. But the analysis of symphonic musical works still has its own characteristics.

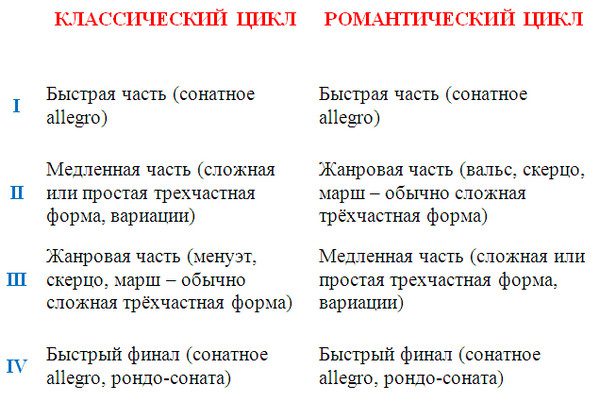

Typically, a symphony consists of four movements. There are two options for the sequence of parts in a symphonic cycle: according to the classical type and according to the romantic type. They differ in the position of the slow part and the so-called genre part (in classical symphonies there is a minuet or scherzo, in romantic symphonies there is a scherzo, sometimes a waltz). Look at the diagram:

Typical musical forms for each of these parts are indicated in brackets on the diagram. Since for a full analysis of a musical work you need to determine its form, read the article “Basic forms of musical works”, the information of which should help you in this matter.

Sometimes the number of parts may be different (for example, 5 parts in Berlioz’s “Fantastastic” Symphony, 3 parts in Scriabin’s “Divine Poem”, 2 parts in Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony, there are also one-movement symphonies – for example, Myaskovsky’s 21st Symphony) . These are, of course, non-standard cycles and the change in the number of parts in them is caused by some features of the composer’s artistic intent (for example, program content).

What is important for analyzing a symphony:

- determine the type of symphonic cycle (classical, romantic, or something unique);

- determine the main tonality of the symphony (for the first movement) and the tonality of each movement separately;

- characterize the figurative and musical content of each of the main themes of the work;

- determine the shape of each part;

- in sonata form, determine the tonality of the main and secondary parts in the exposition and in the reprise, and look for differences in the sound of these parts in the same sections (for example, the main part may change its appearance beyond recognition by the time of the reprise, or may not change at all);

- find and be able to show thematic connections between parts, if any (are there themes that move from one part to another, how do they change?);

- analyze the orchestration (which timbres are the leading ones – strings, woodwinds or brass instruments?);

- determine the role of each part in the development of the entire cycle (which part is the most dramatic, which part is presented as lyrics or reflections, in which parts there is a distraction to other topics, what conclusion is summed up at the end?);

- if the work contains musical quotes, then determine what kind of quotes they are; etc.

Of course, this list can be continued indefinitely. You need to be able to talk about a work with at least the simplest, basic information – it’s better than nothing. And the most important task that you should set for yourself, regardless of whether you are going to do a detailed analysis of a piece of music or not, is direct acquaintance with the music.

In conclusion, as promised, we provide a link to the previous material, where we talked about performance analysis. This article is “Analysis of musical works by specialty”