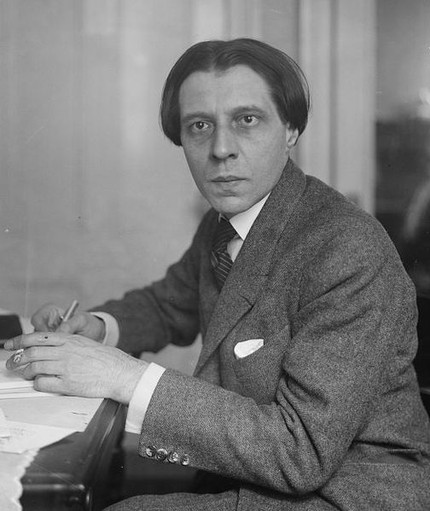

Alfred Cortot |

Alfred Cortot

Alfred Cortot lived a long and unusually fruitful life. He went down in history as one of the titans of world pianism, as the greatest pianist of France in our century. But even if we forget for a moment about the worldwide fame and merits of this piano master, then even then what he did was more than enough to forever inscribe his name in the history of French music.

In essence, Cortot began his career as a pianist surprisingly late – only on the threshold of his 30th birthday. Of course, even before that he devoted a lot of time to the piano. While still a student at the Paris Conservatory – first in the class of Decombe, and after the death of the latter in the class of L. Diemer, he made his debut in 1896, performing Beethoven’s Concerto in G minor. One of the strongest impressions of his youth was for him a meeting – even before entering the conservatory – with Anton Rubinstein. The great Russian artist, after listening to his game, admonished the boy with these words: “Baby, do not forget what I will tell you! Beethoven is not played, but re-composed. These words became the motto of Corto’s life.

- Piano music in the Ozon online store →

And yet, in his student years, Cortot was much more interested in other areas of musical activity. He was fond of Wagner, studied symphonic scores. After graduating from the conservatory in 1896, he successfully declared himself as a pianist in a number of European countries, but soon went to the Wagner city of Bayreuth, where he worked for two years as an accompanist, assistant director, and finally, a conductor under the guidance of the Mohicans of conducting art – X. Richter and F Motlya. Returning then to Paris, Cortot acts as a consistent propagandist of Wagner’s work; under his direction, the premiere of The Death of the Gods (1902) takes place in the capital of France, other operas are being performed. “When Cortot conducts, I have no remarks,” this is how Cosima Wagner herself assessed his understanding of this music. In 1902, the artist founded the Cortot Association of Concerts in the capital, which he led for two seasons, and then became the conductor of the Paris National Society and Popular Concerts in Lille. During the first decade of the XNUMXth century, Cortot presented to the French public a huge number of new works – from The Ring of the Nibelungen to the works of contemporary, including Russian, authors. And later he regularly performed as a conductor with the best orchestras and founded two more groups – the Philharmonic and the Symphony.

Of course, all these years Cortot has not ceased to perform as a pianist. But it is not by chance that we dwelled in such detail on other aspects of his activity. Although it was only after 1908 that piano performance gradually came to the fore in his activities, it was precisely the versatility of the artist that largely determined the distinctive features of his pianistic appearance.

He himself formulated his interpreting credo as follows: “The attitude towards a work can be twofold: either immobility or search. The search for the author’s intention, opposing ossified traditions. The most important thing is to give free rein to the imagination, creating a composition again. This is the interpretation.” And in another case, he expressed the following thought: “The highest destiny of the artist is to revive the human feelings hidden in music.”

Yes, first of all, Cortot was and remained a musician at the piano. Virtuosity never attracted him and was not a strong, conspicuous side of his art. But even such a strict piano connoisseur as G. Schonberg admitted that there was a special demand from this pianist: “Where did he get the time to keep his technique in order? The answer is simple: he didn’t do it at all. Cortot always made mistakes, he had memory lapses. For any other, less significant artist, this would be unforgivable. It didn’t matter to Cortot. This was perceived as shadows are perceived in the paintings of old masters. Because, despite all the mistakes, his magnificent technique was flawless and capable of any “fireworks” if the music required it. The statement of the famous French critic Bernard Gavoti is also noteworthy: “The most beautiful thing about Cortot is that under his fingers the piano ceases to be a piano.”

Indeed, Cortot’s interpretations are dominated by music, dominated by the spirit of the work, the deepest intellect, courageous poetry, the logic of artistic thinking – all that distinguished him from many fellow pianists. And of course, the amazing richness of sound colors, which seemed to surpass the capabilities of an ordinary piano. No wonder Cortot himself coined the term “piano orchestration”, and in his mouth it was by no means just a beautiful phrase. Finally, the amazing freedom of performance, which gave his interpretations and the very process of playing the character of philosophical reflections or excited narrations that inexorably captivated the listeners.

All these qualities made Cortot one of the best interpreters of the romantic music of the last century, primarily Chopin and Schumann, as well as French authors. In general, the artist’s repertoire was very extensive. Along with the works of these composers, he superbly performed sonatas, rhapsodies and transcriptions of Liszt, major works and miniatures by Mendelssohn, Beethoven, and Brahms. Any work acquired from him special, unique features, opened in a new way, sometimes causing controversy among connoisseurs, but invariably delighting the audience.

Cortot, a musician to the marrow of his bones, was not satisfied only with solo repertoire and concerts with an orchestra, he constantly turned to chamber music as well. In 1905, together with Jacques Thibault and Pablo Casals, he founded a trio, whose concerts for several decades – until the death of Thibaut – were holidays for music lovers.

The glory of Alfred Cortot – pianist, conductor, ensemble player – already in the 30s spread around the world; in many countries he was known by records. It was in those days – at the time of his highest heyday – that the artist visited our country. This is how professor K. Adzhemov described the atmosphere of his concerts: “We were looking forward to Cortot’s arrival. In the spring of 1936 he performed in Moscow and Leningrad. I remember his first appearance on the stage of the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory. Having barely taken a place at the instrument, without waiting for silence, the artist immediately “attacked” the theme of Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes. The C-sharp minor chord, with its bright fullness of sound, seemed to cut through the noise of the restless hall. There was an instant silence.

Solemnly, elatedly, oratorically passionately, Cortot recreated romantic images. Over the course of a week, one after another, his performing masterpieces sounded before us: sonatas, ballads, preludes by Chopin, a piano concerto, Schumann’s Kreisleriana, Children’s Scenes, Mendelssohn’s Serious Variations, Weber’s Invitation to Dance, Sonata in B minor and Liszt’s Second Rhapsody… Each piece was imprinted in the mind like a relief image, extremely significant and unusual. The sculptural majesty of sound images was due to the unity of the artist’s powerful imagination and wonderful pianistic skill developed over the years (especially the colorful vibrato of timbres). With the exception of a few academically minded critics, Cortot’s original interpretation won the general admiration of Soviet listeners. B. Yavorsky, K. Igumnov, V. Sofronitsky, G. Neuhaus highly appreciated the art of Korto.

It is also worth quoting here the opinion of K. N. Igumnov, an artist who is in some ways close, but in some ways opposite to the head of French pianists: “He is an artist, equally alien to both spontaneous impulse and outward brilliance. He is somewhat rationalistic, his emotional beginning is subordinate to the mind. His art is exquisite, sometimes difficult. His sound palette is not very extensive, but attractive, he is not drawn to the effects of piano instrumentation, he is interested in cantilena and transparent colors, he does not strive for rich sounds and shows the best side of his talent in the field of lyrics. Its rhythm is very free, its very peculiar rubato sometimes breaks the general line of the form and makes it difficult to perceive the logical connection between individual phrases. Alfred Cortot has found his own language and in this language he retells the familiar works of the great masters of the past. The musical thoughts of the latter in his translation often acquire new interest and significance, but sometimes they turn out to be untranslatable, and then the listener has doubts not about the sincerity of the performer, but about the inner artistic truth of the interpretation. This originality, this inquisitiveness, characteristic of Cortot, awakens the performing idea and does not allow it to settle down on generally recognized traditionalism. However, Cortot cannot be imitated. Accepting it unconditionally, it is easy to fall into inventiveness.

Subsequently, our listeners had the opportunity to get acquainted with the playing of the French pianist from numerous recordings, the value of which does not decrease over the years. For those who listen to them today, it is important to remember the characteristic features of the artist’s art, which are preserved in his recordings. “Anyone who touches his interpretation,” writes one of Cortot’s biographers, “should renounce the deep-rooted delusion that interpretation, supposedly, is the transfer of music while maintaining, above all, fidelity to the musical text, its “letter”. Just as applied to Cortot, such a position is downright dangerous for life – the life of music. If you “control” him with notes in his hands, then the result can only be depressing, since he was not a musical “philologist” at all. Didn’t he sin incessantly and shamelessly in all possible cases – in pace, in dynamics, in torn rubato? Were not his own ideas more important to him than the will of the composer? He himself formulated his position as follows: “Chopin is played not with fingers, but with heart and imagination.” This was his creed as an interpreter in general. The notes interested him not as static codes of laws, but, to the highest degree, as an appeal to the feelings of the performer and listener, an appeal that he had to decipher. Corto was a creator in the broadest sense of the word. Could a pianist of modern formation achieve this? Probably not. But Cortot was not enslaved by today’s desire for technical perfection – he was almost a myth during his lifetime, almost beyond the reach of criticism. They saw in his face not only a pianist, but a personality, and therefore there were factors that turned out to be much higher than the “right” or “false” note: his editorial competence, his unheard-of erudition, his rank as a teacher. All this also created an undeniable authority, which has not disappeared to this day. Cortot could literally afford his mistakes. On this occasion, one can smile ironically, but, despite this, one must listen to his interpretation.”

The glory of Cortot – a pianist, conductor, propagandist – was multiplied by his activities as a teacher and writer. In 1907, he inherited the class of R. Punyo at the Paris Conservatory, and in 1919, together with A. Mange, he founded the Ecole Normale, which soon became famous, where he was director and teacher – he taught summer interpretation courses there. His authority as a teacher was unparalleled, and students literally from all over the world flocked to his class. Among those who studied with Cortot at various times were A. Casella, D. Lipatti, K. Haskil, M. Tagliaferro, S. Francois, V. Perlemuter, K. Engel, E. Heidsieck and dozens of other pianists. Cortot’s books – “French Piano Music” (in three volumes), “Rational Principles of Piano Technique”, “Course of Interpretation”, “Aspects of Chopin”, his editions and methodical works went around the world.

“… He is young and has a completely selfless love for music,” Claude Debussy said about Cortot at the beginning of our century. Corto remained the same young and in love with music throughout his life, and so remained in the memory of everyone who heard him play or communicated with him.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya.