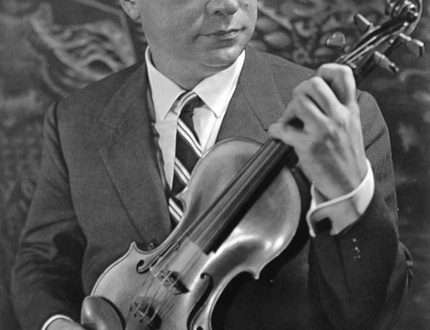

Paul Hindemith |

Paul Hindemith

Our destiny is the music of human creations And listen silently to the music of the worlds. Summon the minds of distant generations For a fraternal spiritual meal. G. Hesse

P. Hindemith is the largest German composer, one of the recognized classics of music of the XNUMXth century. Being a personality of a universal scale (conductor, viola and viola d’amore performer, music theorist, publicist, poet – author of the texts of his own works) – Hindemith was just as universal in his composing activity. There is no such type and genre of music that would not be covered by his work – be it a philosophically significant symphony or an opera for preschoolers, music for experimental electronic instruments or pieces for an old string ensemble. There is no such instrument that would not appear in his works as a soloist and on which he could not play himself (for, according to contemporaries, Hindemith was one of the few composers who could perform almost all the parts in his orchestral scores, hence – firmly assigned to him the role of “all-musician” – All-round-musiker). The composer’s musical language itself, which has absorbed various experimental trends of the XNUMXth century, is also marked by the desire for inclusiveness. and at the same time constantly rushing to the origins – to J. S. Bach, later – to J. Brahms, M. Reger and A. Bruckner. Hindemith’s creative path is the path of the birth of a new classic: from the polemical fuse of youth to an increasingly serious and thoughtful assertion of his artistic credo.

The beginning of Hindemith’s activity coincided with the 20s. – a strip of intensive searches in European art. The expressionist influences of these years (the opera The Killer, the Hope of Women, based on a text by O. Kokoschka) relatively quickly give way to anti-romantic declarations. Grotesque, parody, caustic ridicule of all pathos (the opera News of the Day), an alliance with jazz, the noises and rhythms of the big city (piano suite 1922) – everything was united under the common slogan – “down with romanticism.” The young composer’s program of action is unequivocally reflected in his author’s remarks, like the one that accompanies the finale of the viola Sonata op. 21 #1: “The pace is frantic. The beauty of sound is a secondary matter. However, even then neoclassical orientation dominated in the complex spectrum of stylistic searches. For Hindemith, neoclassicism was not only one of many linguistic mannerisms, but above all a leading creative principle, the search for a “strong and beautiful form” (F. Busoni), the need to develop stable and reliable norms of thinking, dating back to the old masters.

By the second half of the 20s. finally formed the individual style of the composer. The harsh expression of Hindemith’s music gives reason to liken it to “the language of wood engraving.” Introduction to the musical culture of the Baroque, which became the center of Hindemith’s neoclassical passions, was expressed in the widespread use of the polyphonic method. Fugues, passacaglia, the technique of linear polyphony saturate compositions of various genres. Among them are the vocal cycle “The Life of Mary” (on R. Rilke’s station), as well as the opera “Cardillac” (based on the short story by T. A. Hoffmann), where the inherent value of the musical laws of development is perceived as a counterbalance to the Wagnerian “musical drama”. Along with the named works to the best creations of Hindemith of the 20s. (Yes, perhaps, and in general, his best creations) include cycles of chamber instrumental music – sonatas, ensembles, concertos, where the composer’s natural predisposition to think in purely musical concepts found the most fertile ground.

Hindemith’s extraordinarily productive work in instrumental genres is inseparable from his performing image. As a violist and member of the famous L. Amar quartet, the composer gave concerts in various countries (including the USSR in 1927). In those years, he was the organizer of the festivals of new chamber music in Donaueschingen, inspired by the novelties that sounded there and at the same time defining the general atmosphere of the festivals as one of the leaders of the musical avant-garde.

In the 30s. Hindemith’s work gravitates toward greater clarity and stability: the natural reaction of the “sludge” of the experimental currents that were seething until now was experienced by all European music. For Hindemith, the ideas of Gebrauchsmusik, the music of everyday life, played an important role here. Through various forms of amateur music-making, the composer intended to prevent the loss of the mass listener by modern professional creativity. However, a certain seal of self-restraint now characterizes not only his applied and instructive experiments. The ideas of communication and mutual understanding based on music do not leave the German master when creating compositions of the “high style” – just as until the very end he retains faith in the good will of people who love art, that “Evil people have no songs” ( “Bose Menschen haben keine Lleder”).

The search for a scientifically objective basis for musical creativity, the desire to theoretically comprehend and substantiate the eternal laws of music, due to its physical nature, also led to the ideal of a harmonious, classically balanced statement by Hindemith. This is how the “Guide to Composition” (1936-41) was born – the fruit of many years of work by Hindemith, a scientist and teacher.

But, perhaps, the most important reason for the composer’s departure from the self-sufficing stylistic audacity of the early years was new creative super-tasks. Hindemith’s spiritual maturity was stimulated by the very atmosphere of the 30s. – the complex and terrible situation of fascist Germany, which required the artist to mobilize all moral forces. It is no coincidence that the opera The Painter Mathis (1938) appeared at that time, a deep social drama that was perceived by many in direct consonance with what was happening (eloquent associations were evoked, for example, by the scene of the burning of Lutheran books on the market square in Mainz). The theme of the work itself sounded very relevant – the artist and society, developed on the basis of the legendary biography of Mathis Grunewald. It is noteworthy that Hindemith’s opera was banned by the fascist authorities and soon began its life in the form of a symphony of the same name (3 parts of it are called the paintings of the Isenheim Altarpiece, painted by Grunewald: “Concert of Angels”, “The Entombment”, “The Temptations of St. Anthony”) .

The conflict with the fascist dictatorship became the reason for the composer’s long and irretrievable emigration. However, living for many years away from his homeland (mainly in Switzerland and the USA), Hindemith remained true to the original traditions of German music, as well as to his chosen composer’s path. In the post-war years, he continued to give preference to instrumental genres (the Symphonic Metamorphoses of Weber’s Themes, the Pittsburgh and Serena symphonies, new sonatas, ensembles, and concertos were created). Hindemith’s most significant work of recent years is the symphony “Harmony of the World” (1957), which arose on the material of the opera of the same name (which tells about the spiritual quest of the astronomer I. Kepler and his difficult fate). The composition ends with a majestic passacaglia, depicting a round dance of heavenly bodies and symbolizing the harmony of the universe.

Belief in this harmony—despite the chaos of real life—pervaded all of the composer’s later work. The preaching-protective pathos sounds in it more and more insistently. In The Composer’s World (1952), Hindemith declares war on the modern “entertainment industry” and, on the other hand, on the elitist technocracy of the latest avant-garde music, equally hostile, in his opinion, to the true spirit of creativity. Hindemith’s guarding had obvious costs. His musical style is from the 50s. sometimes fraught with academic leveling; not free from didactics and critical attacks of the composer. And yet, it is precisely in this craving for harmony, which is experiencing – moreover, in Hindemith’s own music – a considerable force of resistance, that the main moral and aesthetic “nerve” of the best creations of the German master lies. Here he remained a follower of the great Bach, responding at the same time to all the “sick” questions of life.

T. Left

- Opera works of Hindemith →