Nicolai Gedda |

Nicolai gedda

Nikolai Gedda was born in Stockholm on July 11, 1925. His teacher was the Russian organist and choirmaster Mikhail Ustinov, in whose family the boy lived. Ustinov also became the first teacher of the future singer. Nicholas spent his childhood in Leipzig. Here, at the age of five, he began to learn to play the piano, as well as to sing in the choir of the Russian church. They were led by Ustinov. “At this time,” the artist later recalled, “I learned two very important things for myself: firstly, that I passionately love music, and secondly, that I have absolute pitch.

… I have been asked countless times where I got such a voice. To this I can only answer one thing: I received it from God. I could have inherited the traits of an artist from my maternal grandfather. I myself have always considered my singing voice as something to be controlled. Therefore, I have always tried to take care of my voice, develop it, live in such a way as not to damage my gift.

In 1934, together with his adoptive parents, Nikolai returned to Sweden. Graduated from the gymnasium and began working days.

“…One summer I worked for Sarah Leander’s first husband, Nils Leander. He had a publishing house on the Regeringsgatan, they published a large reference book about filmmakers, not only about directors and actors, but also about cashiers in cinemas, mechanics and controllers. My job was to pack this work in a postal package and send it out all over the country by cash on delivery.

In the summer of 1943, my father found work in the forest: he chopped wood for a peasant near the town of Mersht. I went with him and helped. It was a stunningly beautiful summer, we got up at five in the morning, at the most pleasant time – there was still no heat and no mosquitoes either. We worked until three and went to rest. We lived in a peasant’s house.

In the summer of 1944 and 1945, I worked at the Nurdiska Company, in the department that prepared donation parcels for shipment to Germany – this was an organized aid, headed by Count Folke Bernadotte. The Nurdiska Company had special premises for this on Smålandsgatan – packages were packed there, and I wrote notices …

… A real interest in music was awakened by the radio, when during the war years I lay for hours and listened – first to Gigli, and then to Jussi Björling, the German Richard Tauber and the Dane Helge Rosvenge. I remember my admiration for the tenor Helge Roswenge – he had a brilliant career in Germany during the war. But Gigli evoked the most stormy feelings in me, especially attracted by his repertoire – arias from Italian and French operas. I spent many evenings at the radio, listening and listening endlessly.

After serving in the army, Nikolai entered the Stockholm Bank as an employee, where he worked for several years. But he continued to dream of a career as a singer.

“Good friends of my parents advised me to take lessons from the Latvian teacher Maria Vintere, before coming to Sweden she sang at the Riga Opera. Her husband was a conductor in the same theater, with whom I later began to study music theory. Maria Wintere gave lessons in the rented assembly hall of the school in the evenings, during the day she had to earn a living by ordinary work. I studied with her for a year, but she did not know how to develop the most necessary thing for me – the technique of singing. Apparently, I have not made any progress with her.

I talked to some clients at the bank office about music when I helped them unlock safes. Most of all we talked with Bertil Strange – he was a horn player in the Court Chapel. When I told him about the troubles with learning to sing, he named Martin Eman: “I think he will suit you.”

… When I sang all my numbers, involuntary admiration spilled out of him, he said that he had never heard anyone sing these things so beautifully – of course, except for Gigli and Björling. I was happy and decided to work with him. I told him that I work in a bank, that the money I earn goes to support my family. “Let’s not make a problem out of paying for lessons,” Eman said. The first time he offered to study with me for free.

In the autumn of 1949 I started studying with Martin Eman. A few months later, he gave me a trial audition for the Christina Nilsson Scholarship, at that time it was 3000 crowns. Martin Eman sat on the jury with the then chief conductor of the opera, Joel Berglund, and court singer Marianne Merner. Subsequently, Eman said that Marianne Merner was delighted, which could not be said about Berglund. But I received a bonus, and one, and now I could pay Eman for lessons.

While I was handing over the checks, Eman called one of the directors of the Scandinavian Bank, whom he knew personally. He asked me to take on a part-time job to give me the opportunity to really, seriously continue singing. I was transferred to the main office on Gustav Adolf Square. Martin Eman also organized a new audition for me at the Academy of Music. Now they accepted me as a volunteer, which meant that, on the one hand, I had to take exams, and on the other hand, I was exempted from compulsory attendance, since I had to spend half a day at the bank.

I continued to study with Eman, and every day of that time, from 1949 to 1951, was filled with work. These years were the most wonderful in my life, then so much suddenly opened up for me …

… What Martin Eman taught me first of all was how to “prepare” the voice. This is done not only due to the fact that you darken towards the “o” and also use the change in the width of the opening of the throat and the help of the support. The singer usually breathes like all people, not only through the throat, but also deeper, with the lungs. Achieving proper breathing technique is like filling a decanter with water, you have to start from the bottom. They fill the lungs deeply – so that it is enough for a long phrase. Then it is necessary to solve the problem of how to use the air carefully so as not to be left without it until the end of the phrase. All this Eman could teach me perfectly, because he himself was a tenor and knew these problems thoroughly.

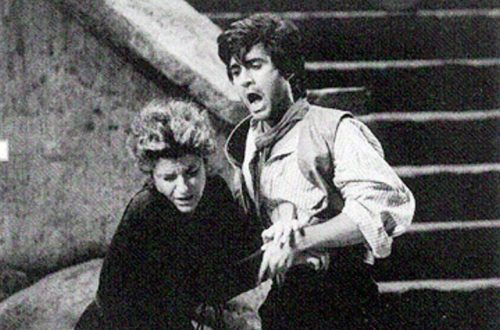

April 8, 1952 was the debut of Hedda. The next day, many Swedish newspapers started talking about the newcomer’s great success.

Just at that time, the English record company EMAI was looking for a singer for the role of the Pretender in Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov, which was to be performed in Russian. The well-known sound engineer Walter Legge came to Stockholm to search for a vocalist. The management of the opera house invited Legge to organize an audition for the most gifted young singers. V.V. tells about Gedda’s speech. Timokhin:

“The singer performed for Legge the “Aria with a Flower” from “Carmen”, flashing a magnificent B-flat. After that, Legge asked the young man to sing the same phrase according to the author’s text – diminuendo and pianissimo. The artist fulfilled this wish without any effort. That same evening, Gedda sang, now for Dobrovijn, again the “aria with a flower” and two arias by Ottavio. Legge, his wife Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and Dobrovein were unanimous in their opinion – they had an outstanding singer in front of them. Immediately a contract was signed with him to perform the part of the Pretender. However, this was not the end of the matter. Legge knew that Herbert Karajan, who staged Mozart’s Don Giovanni at La Scala, had great difficulty in choosing a performer for the role of Ottavio, and sent a short telegram directly from Stockholm to the conductor and director of the theater Antonio Ghiringelli: “I found the ideal Ottavio “. Ghiringelli immediately called Gedda to an audition at La Scala. Giringelli later said that in a quarter of a century of his tenure as a director, he had never met a foreign singer who would have such a perfect command of the Italian language. Gedda was immediately invited to the role of Ottavio. His performance was a great success, and the composer Carl Orff, whose Triumphs trilogy was just being prepared for staging at La Scala, immediately offered the young artist the part of the Bridegroom in the final part of the trilogy, Aphrodite’s Triumph. So, just a year after the first performance on stage, Nikolai Gedda gained a reputation as a singer with a European name.

In 1954, Gedda sang in three major European music centers at once: in Paris, London and Vienna. This is followed by a concert tour of the cities of Germany, a performance at a music festival in the French city of Aix-en-Provence.

In the mid-fifties, Gedda already has international fame. In November 1957, he made his first appearance in Gounod’s Faust at the New York Metropolitan Opera House. Further here he sang annually for more than twenty seasons.

Shortly after his debut at the Metropolitan, Nikolai Gedda met the Russian singer and vocal teacher Polina Novikova, who lived in New York. Gedda greatly appreciated her lessons: “I believe that there is always a danger of small mistakes that can become fatal and gradually lead the singer down the wrong path. The singer cannot, like an instrumentalist, hear himself, and therefore constant monitoring is necessary. Just lucky that I met a teacher for whom the art of singing has become a science. At one time, Novikova was very famous in Italy. Her teacher was Mattia Battistini himself. She had a good school and the famous bass-baritone George London.

Many bright episodes of the artistic biography of Nikolai Gedda are associated with the Metropolitan Theater. In October 1959, his performance in Massenet’s Manon drew rave reviews from the press. Critics did not fail to note the elegance of phrasing, the amazing grace and nobility of the singer’s performing manner.

Among the roles sung by Gedda on the New York stage, Hoffmann (“The Tales of Hoffmann” by Offenbach), Duke (“Rigoletto”), Elvino (“Sleepwalker”), Edgar (“Lucia di Lammermoor”) stand out. Regarding the performance of the role of Ottavio, one of the reviewers wrote: “As a Mozartian tenor, Hedda has few rivals on the modern opera stage: perfect freedom of performance and refined taste, a huge artistic culture and a remarkable gift of a virtuoso singer allow him to achieve amazing heights in Mozart’s music.”

In 1973, Gedda sang in Russian the part of Herman in The Queen of Spades. The unanimous delight of the American listeners was also caused by another “Russian” work of the singer – the part of Lensky.

“Lensky is my favorite part,” says Gedda. “There is so much love and poetry in it, and at the same time so much true drama.” In one of the comments on the performance of the singer, we read: “Speaking in Eugene Onegin, Gedda finds herself in an emotional element so close to herself that the lyricism and poetic enthusiasm inherent in the image of Lensky receive an especially touching and deeply exciting embodiment from the artist. It seems that the very soul of the young poet sings, and the bright impulse, his dreams, thoughts about parting with life, the artist conveys with captivating sincerity, simplicity and sincerity.

In March 1980, Gedda visited our country for the first time. He performed on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater of the USSR precisely in the role of Lensky and with great success. Since that time, the singer often visited our country.

Art critic Svetlana Savenko writes:

“Without exaggeration, the Swedish tenor can be called a universal musician: a variety of styles and genres are available to him – from Renaissance music to Orff and Russian folk songs, a variety of national manners. He is equally convincing in Rigoletto and Boris Godunov, in Bach’s mass and in Grieg’s romances. Perhaps this reflects the flexibility of a creative nature, characteristic of an artist who grew up on foreign soil and was forced to consciously adapt to the surrounding cultural environment. But after all, flexibility also needs to be preserved and cultivated: by the time Gedda matured, he could well have forgotten the Russian language, the language of his childhood and youth, but this did not happen. The party of Lensky in Moscow and Leningrad sounded in his interpretation extremely meaningful and phonetically impeccable.

The performing style of Nikolai Gedda happily combines the features of several, at least three, national schools. It is based on the principles of Italian bel canto, the mastery of which is necessary for any singer who wants to devote himself to operatic classics. Hedda’s singing is distinguished by the wide breathing of a melodic phrase typical of bel canto, combined with the perfect evenness of sound production: each new syllable smoothly replaces the previous one, without violating a single vocal position, no matter how emotional the singing may be. Hence the timbre unity of Hedda’s voice range, the absence of “seams” between the registers, which is sometimes found even among great singers. His tenor is equally beautiful in every register.”