Mikhail Izrailevich Vaiman |

Mikhail Vaiman

To the essays on Oistrakh and Kogan, the most prominent representatives of the Soviet violin school, we add an essay on Mikhail Vayman. In the performance work of Vaiman, another very important line of Soviet performance was revealed, which has a fundamental ideological and aesthetic significance.

Vayman is a graduate of the Leningrad school of violinists, which produced such major performers as Boris Gutnikov, Mark Komissarov, Dina Shneiderman, the Bulgarian Emil Kamillarov, and others. According to his creative goals, Vayman is the most interesting figure for a researcher. This is a violinist walking in the art of high ethical ideals. He inquisitively seeks to penetrate into the deep meaning of the music he performs, and mainly in order to find an uplifting note in it. In Wyman, the thinker in the field of music unites with the “artist of the heart”; his art is emotional, lyrical, it is imbued with the lyrics of a clever, sophisticated philosophy of a humanistic-ethical order. It is no coincidence that the evolution of Wymann as a performer went from Bach to Frank and Beethoven, and Beethoven of the last period. This is his conscious credo, worked out and gained by suffering as a result of long reflections on the goals and objectives of art. He argues that art requires a “pure heart” and that purity of thoughts is an indispensable condition for a truly inspired performing art. Mundane natures, – says Wyman, when talking with him about music, – are able to create only mundane images. The artist’s personality leaves an indelible mark on everything he does.

However, “purity”, “elevation” can be different. They can mean, for example, an over-life aestheticized category. For Wyman, these concepts are entirely connected with the noble idea of goodness and truth, with humanity, without which art is dead. Wyman considers art from a moral standpoint and sees this as the main duty of the artist. Least of all, Wyman is fascinated by “violinism”, not warmed by the heart and soul.

In his aspirations, Vayman is in many respects close to Oistrakh of recent years, and of foreign violinists – to Menuhin. He deeply believes in the educational power of art and is intransigent towards works that carry cold reflection, skepticism, irony, decay, emptiness. He is even more alien to rationalism, constructivist abstractions. For him, art is a way of philosophical knowledge of reality through the disclosure of the psychology of a contemporary. Cognitiveness, careful comprehension of the artistic phenomenon underlie his creative method.

Wyman’s creative orientation leads to the fact that, having an excellent command of large concert forms, he is more and more inclined towards intimacy, which is for him a means to highlight the subtlest nuances of feeling, the slightest shades of emotions. Hence the desire for a declamatory manner of playing, a kind of “speech” intonation through detailed stroke techniques.

To what style category can Wyman be classified? Who is he, “classic”, according to his interpretation of Bach and Beethoven, or “romantic”? Of course, a romantic in terms of an extremely romantic perception of music and attitude towards it. Romantic are his searches for a lofty ideal, his chivalrous service to music.

Mikhail Vayman was born on December 3, 1926 in the Ukrainian city of Novy Bug. When he was seven years old, the family moved to Odessa, where the future violinist spent his childhood. His father belonged to the number of versatile professional musicians, of whom there were many at that time in the provinces; he conducted, played the violin, gave violin lessons, and taught theoretical subjects at the Odessa Music School. The mother did not have a musical education, but, closely connected with the musical environment through her husband, she passionately desired that her son also become a musician.

The first contacts of young Mikhail with music took place in the New Bug, where his father led the orchestra of wind instruments in the city’s House of Culture. The boy invariably accompanied his father, became addicted to playing the trumpet and participated in several concerts. But the mother protested, believing that it was harmful for a child to play a wind instrument. Moving to Odessa put an end to this hobby.

When Misha was 8 years old, he was brought to P. Stolyarsky; the acquaintance ended with the enrollment of Wyman in the music school of a wonderful children’s teacher. Vaiman’s school was taught mainly by Stolyarsky’s assistant L. Lembergsky, but under the supervision of the professor himself, who regularly checked how the talented pupil was developing. This continued until 1941.

On July 22, 1941, Vayman’s father was drafted into the army, and in 1942 he died at the front. The mother was left alone with her 15-year-old son. They received the news of their father’s death when they were already far from Odessa – in Tashkent.

A conservatory evacuated from Leningrad settled in Tashkent, and Vayman was enrolled in a ten-year school under it, in the class of Professor Y. Eidlin. Enrolling immediately in the 8th grade, in 1944 Wyman graduated from high school and immediately passed the exam for the conservatory. At the conservatory, he also studied with Eidlin, a deep, talented, unusually serious teacher. His merit is the formation in Wyman of the qualities of an artist-thinker.

Even during the period of school studies, they started talking about Wyman as a promising violinist who has all the data to develop into a major concert soloist. In 1943, he was sent to a review of talented students of music schools in Moscow. It was a remarkable undertaking carried out at the height of the war.

In 1944 the Leningrad Conservatory returned to its native city. For Wyman, the Leningrad period of life began. He becomes a witness to the rapid revival of the age-old culture of the city, its traditions, eagerly absorbs everything that this culture carries in itself – its special severity, full of inner beauty, sublime academicism, a penchant for harmony and completeness of forms, high intelligence. These qualities clearly make themselves felt in his performance.

A notable milestone in the life of Wyman is 1945. A young student of the Leningrad Conservatory is sent to Moscow to the first post-war All-Union competition of performing musicians and wins a diploma with honors there. In the same year, his first performance took place in the Great Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonic with an orchestra. He performed Steinberg’s Concerto. After the end of the concert, Yury Yuriev, People’s Artist of the USSR, came to the dressing room. “Young man. he said, touched. – today is your debut – remember it until the end of your days, because this is the title page of your artistic life. “I remember,” Wyman says. — I still remember these words as parting words of the great actor, who always sacrificially served art. How wonderful it would be if we all carried at least a particle of his burning in our hearts!”

At the qualifying test for the International J. Kubelik Competition in Prague, held in Moscow, an enthusiastic audience did not let Vayman off the stage for a long time. It was a real success. However, at the competition, Wyman played less successfully and did not win the place that he could count on after the Moscow performance. An incomparably better result – the second prize – was achieved by Weimann in Leipzig, where he was sent in 1950 to the J.-S. Bach. The jury praised his interpretation of Bach’s works as outstanding in thoughtfulness and style.

Wyman carefully keeps the gold medal received at the Belgian Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels in 1951. It was his last and brightest competitive performance. The world music press spoke about him and Kogan, who received the first prize. Again, as in 1937, the victory of our violinists was assessed as the victory of the entire Soviet violin school.

After the competition, Wyman’s life becomes normal for a concert artist. Many times he travels around Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic (he was in the German Democratic Republic 19 times!); concerts in Finland. Norway, Denmark, Austria, Belgium, Israel, Japan, England. Everywhere a huge success, a well-deserved admiration for his clever and noble art. Soon Wyman will be recognized in the United States, with which a contract has already been signed for his tour.

In 1966, the outstanding Soviet artist was awarded the title of Honored Artist of the RSFSR.

Wherever Wyman performs, his game is evaluated with extraordinary warmth. She touches hearts, delights with her expressive qualities, although his technical mastery is invariably indicated in the reviews. “Mikhail Vayman’s playing from the first measure of the Bach Concerto to the last stroke of the bow in Tchaikovsky’s bravura work was elastic, resilient, and brilliant, thanks to which he is in the forefront of world-famous violinists. Something very noble was felt in the refined culture of his performance. The Soviet violinist is not only a brilliant virtuoso, but also a very intelligent, sensitive musician…”

“Obviously, the most significant thing in Wyman’s game is warmth, beauty, love. One movement of the bow expresses many shades of feelings,” the newspaper “Kansan Uutiset” (Finland) noted.

In Berlin, in 1961, Wymann performed concertos by Bach, Beethoven and Tchaikovsky with Kurt Sanderling at the conductor’s stand. “This concert, which has become a truly real event, confirmed that the friendship of the venerable conductor Kurt Sanderling with the 33-year-old Soviet artist is based on deeply human and artistic principles.”

In the homeland of Sibelius in April 1965, Vayman performed a concerto by the great Finnish composer and delighted even phlegmatic Finns with his playing. “Mikhail Vayman showed himself to be a master in his performance of the Sibelius Concerto. He began as if from afar, thoughtfully, carefully following the transitions. The lyrics of the adagio sounded noble under his bow. In the finale, within the framework of a moderate pace, he played with difficulties “fon aben” (haughtily.— L.R.), as Sibelius characterized his opinion on how this part should be performed. For the last pages, Wyman had the spiritual and technical resources of a great virtuoso. He threw them into the fire, leaving, however, a certain marginal (marginal notes, in this case, what remains in reserve) as a reserve. He never crosses the last line. He is a virtuoso to the last stroke,” wrote Eric Tavastschera in the newspaper Helsingen Sanomat on April 2, 1965.

And other reviews of Finnish critics are similar: “One of the first virtuosos of his time”, “Great Master”, “Purity and impeccability of technique”, “Originality and maturity of interpretation” – these are the assessments of the performance of Sibelius and Tchaikovsky concertos, with which Vayman and the Leningradskaya Orchestra philharmonics under the direction of A. Jansons toured Finland in 1965.

Wyman is a musician-thinker. For many years he has been occupied with the problem of modern interpretation of Bach’s works. A few years ago, with the same persistence, he switched to solving the problem of Beethoven’s legacy.

With difficulty, he departed from the romanticized manner of performing Bach’s compositions. Returning to the originals of the sonatas, he searched for the primary meaning in them, clearing them of the patina of age-old traditions that had left a trace of their understanding of this music. And Bach’s music under the bow of Weimann spoke in a new way. It spoke, because unnecessary leagues were discarded, and the declamatory specificity of Bach’s style turned out to be revealed. “Melodic recitation” – this is how Wyman performed Bach’s sonatas and partitas. Developing various techniques of recitative-declamatory technique, he dramatized the sound of these works.

The more creative thought Wyman was occupied with the problem of ethos in music, the more resolutely he felt in himself the need to come to the music of Beethoven. Work began on a violin concerto and a cycle of sonatas. In both genres, Wyman primarily sought to reveal the ethical principle. He was interested not so much in heroism and drama as in the majestically lofty aspirations of Beethoven’s spirit. “In our age of skepticism and cynicism, irony and sarcasm, from which humanity has long been tired,” says Wyman, “a musician must call with his art to something else — to faith in the height of human thoughts, in the possibility of goodness, in recognition of the need for ethical duty, and on all this is the most perfect answer is in the music of Beethoven, and the last period of creativity.

In the cycle of sonatas, he went from the last, the Tenth, and as if “spread” its atmosphere to all sonatas. The same is true in the concerto, where the second theme of the first part and the second part became the center, elevated and purified, presented as a kind of ideal spiritual category.

In the profound philosophical and ethical solution of the cycle of Beethoven’s sonatas, a truly innovative solution, Wyman was greatly assisted by his collaboration with the remarkable pianist Maria Karandasheva. In the sonatas, two outstanding like-minded artists met for joint action, and Karandasheva’s will, strictness and severity, merging with the amazing spirituality of Wyman’s performance, gave excellent results. For three evenings on October 23, 28 and November 3, 1965, in the Glinka Hall in Leningrad, this “story about a Man” unfolded before the audience.

The second and no less important sphere of Waiman’s interests is modernity, and primarily Soviet. Even in his youth, he devoted a lot of energy to the performance of new works by Soviet composers. With the Concert of M. Steinberg in 1945, his artistic path began. This was followed by the Lobkowski Concerto, which was performed in 1946; in the first half of the 50s, Vaiman edited and performed the Concerto by the Georgian composer A. Machavariani; in the second half of the 30s – B. Kluzner’s Concert. He was the first performer of the Shostakovich Concerto among Soviet violinists after Oistrakh. Vaiman had the honor to perform this Concerto at the evening dedicated to the composer’s 50th birthday in 1956 in Moscow.

Vaiman treats the works of Soviet composers with exceptional attention and care. In recent years, just as in Moscow to Oistrakh and Kogan, so in Leningrad, almost all composers who create music for the violin turn to Vaiman. At the decade of Leningrad art in Moscow in December 1965, Vaiman brilliantly played the Concerto by B. Arapov, at the “Leningrad Spring” in April 1966 – the Concerto by V. Salmanov. Now he is working on concerts by V. Basner and B. Tishchenko.

Wyman is an interesting and very creative teacher. He is an art teacher. This usually means neglecting the technical side of training. In this case, such one-sidedness is excluded. From his teacher Eidlin, he inherited an analytical attitude towards technology. He has well-thought-out, systematic views on each element of violin craftsmanship, surprisingly accurately recognizes the causes of a student’s difficulties and knows how to eliminate shortcomings. But all this is subject to the artistic method. He makes students “be poets”, leads them from handicraft to the highest spheres of art. Each of his students, even those with average abilities, acquires the qualities of an artist.

“Violinists from many countries studied and study with him: Sipika Leino and Kiiri from Finland, Paole Heikelman from Denmark, Teiko Maehashi and Matsuko Ushioda from Japan (the latter won the title of laureate of the Brussels Competition in 1963 and the Moscow Tchaikovsky Competition in 1966 d.), Stoyan Kalchev from Bulgaria, Henrika Cszionek from Poland, Vyacheslav Kuusik from Czechoslovakia, Laszlo Kote and Androsh from Hungary. The Soviet students of Wyman are the diploma winner of the All-Russian Competition Lev Oskotsky, the winner of the Paganini Competition in Italy (1965) Philip Hirshhorn, the winner of the International Tchaikovsky Competition in 1966 Zinovy Vinnikov.

Weimann’s great and fruitful pedagogical activity cannot be viewed outside of his studies in Weimar. For many years, in the former residence of Liszt, international music seminars have been held there every July. The government of the GDR invites the largest musicians-teachers from different countries to them. Violinists, cellists, pianists and musicians of other specialties come here. For seven consecutive years, Vayman, the only violinist in the USSR, has been invited to lead the violin class.

Classes are held in the form of open lessons, in the presence of an audience of 70-80 people. In addition to teaching, Wymann gives concerts every year in Weimar with a varied program. They are, as it were, an artistic illustration for the seminar. In the summer of 1964, Wyman performed three sonatas for solo violin by Bach here, revealing his understanding of the music of this composer on them; in 1965 he played the Beethoven Concertos.

For outstanding performing and teaching activities in 1965, Wyman was awarded the title of honorary senator of the F. Liszt Higher Musical Academy. Vayman is the fourth musician to receive this title: the first was Franz Liszt, and immediately before Vayman, Zoltan Kodály.

Wyman’s creative biography is by no means finished. His demands on himself, the tasks that he sets for himself, serve as a guarantee that he will justify the high rank given to him in Weimar.

L. Raaben, 1967

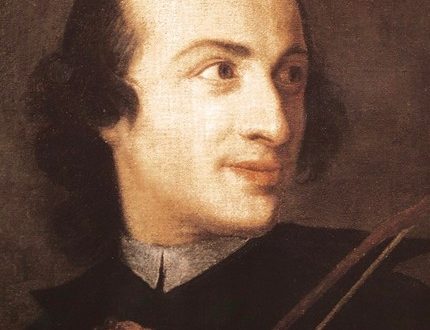

In the photo: conductor – E. Mravinsky, soloist – M. Vayman, 1967