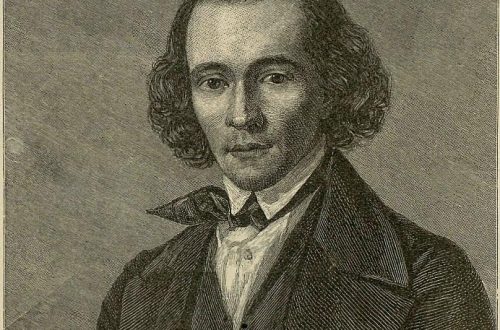

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka |

Michael Glinka

We have a big task ahead of us! Develop your own style and pave a new path for Russian opera music. M. Glinka

Glinka … corresponded to the needs of the time and the fundamental essence of his people to such an extent that the work he started flourished and grew in the shortest possible time and gave such fruits that were unknown in our fatherland during all the centuries of his historical life. V. Stasov

In the person of M. Glinka, Russian musical culture for the first time put forward a composer of world significance. Based on the centuries-old traditions of Russian folk and professional music, the achievements and experience of European art, Glinka completed the process of forming a national school of composers, which won in the XNUMXth century. one of the leading places in European culture, became the first Russian classical composer. In his work, Glinka expressed the progressive ideological aspirations of the time. His works are imbued with the ideas of patriotism, faith in the people. Like A. Pushkin, Glinka sang the beauty of life, the triumph of reason, goodness, justice. He created an art so harmonious and beautiful that one does not get tired of admiring it, discovering more and more perfections in it.

What shaped the personality of the composer? Glinka writes about this in his “Notes” – a wonderful example of memoir literature. He calls Russian songs the main childhood impressions (they were “the first reason that later I began to develop mainly Russian folk music”), as well as the uncle’s serf orchestra, which he “loved most of all.” As a boy, Glinka played flute and violin in it, and as he grew older, he conducted. “The liveliest poetic delight” filled his soul with the ringing of bells and church singing. Young Glinka drew well, passionately dreamed of traveling, was distinguished by his quick mind and rich imagination. Two great historical events were the most important facts of his biography for the future composer: the Patriotic War of 1812 and the Decembrist uprising in 1825. They determined the main idea of uXNUMXbuXNUMXbcreativity (“Let us dedicate our souls to the Fatherland with wonderful impulses”), as well as political convictions. According to a friend of his youth N. Markevich, “Mikhailo Glinka … did not sympathize with any Bourbons.”

A beneficial effect on Glinka was his stay in the St. Petersburg Noble Boarding School (1817-22), famous for its progressively thinking teachers. His tutor at the boarding school was V. Küchelbecker, the future Decembrist. Youth passed in an atmosphere of passionate political and literary disputes with friends, and some of the people close to Glinka after the defeat of the Decembrist uprising were among those exiled to Siberia. No wonder Glinka was interrogated about his connections with the “rebels”.

In the ideological and artistic formation of the future composer, Russian literature played a significant role with its interest in history, creativity, and the life of the people; direct communication with A. Pushkin, V. Zhukovsky, A. Delvig, A. Griboyedov, V. Odoevsky, A. Mitskevich. The musical experience was also varied. Glinka took piano lessons (from J. Field, and then from S. Mayer), learned to sing and play the violin. He often visited theaters, attended musical evenings, played music in 4 hands with the brothers Vielgorsky, A. Varlamov, began to compose romances, instrumental plays. In 1825, one of the masterpieces of Russian vocal lyrics appeared – the romance “Do not tempt” to the verses of E. Baratynsky.

Many bright artistic impulses were given to Glinka by travel: a trip to the Caucasus (1823), a stay in Italy, Austria, Germany (1830-34). A sociable, ardent, enthusiastic young man, who combined kindness and straightforwardness with poetic sensitivity, he easily made friends. In Italy, Glinka became close to V. Bellini, G. Donizetti, met with F. Mendelssohn, and later G. Berlioz, J. Meyerbeer, S. Moniuszko would appear among his friends. Eagerly absorbing various impressions, Glinka studied seriously and inquisitively, having completed his musical education in Berlin with the famous theorist Z. Dehn.

It was here, far from his homeland, that Glinka fully realized his true destiny. “The idea of national music … became clearer and clearer, the intention arose to create a Russian opera.” This plan was realized upon his return to St. Petersburg: in 1836, the opera Ivan Susanin was completed. Its plot, prompted by Zhukovsky, made it possible to embody the idea of a feat in the name of saving the motherland, which was extremely captivating for Glinka. This was new: in all European and Russian music there was no patriotic hero like Susanin, whose image generalizes the best typical features of the national character.

The heroic idea is embodied by Glinka in forms characteristic of national art, based on the richest traditions of Russian songwriting, Russian professional choral art, which organically combined with the laws of European opera music, with the principles of symphonic development.

The premiere of the opera on November 27, 1836 was perceived by leading figures of Russian culture as an event of great significance. “With Glinka’s opera, there is … a new element in Art, and a new period begins in its history – the period of Russian music,” Odoevsky wrote. The opera was highly appreciated by Russians, later foreign writers and critics. Pushkin, who was present at the premiere, wrote a quatrain:

Listening to this news Envy, darkened by malice, Let it gnash, but Glinka Can’t get stuck in the dirt.

Success inspired the composer. Immediately after the premiere of Susanin, work began on the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila (based on the plot of Pushkin’s poem). However, all sorts of circumstances: an unsuccessful marriage that ended in divorce; the highest mercy – service in the Court Choir, which took a lot of energy; the tragic death of Pushkin in a duel, which destroyed the plans for joint work on the work – all this did not favor the creative process. Interfered with household disorder. For some time Glinka lived with the playwright N. Kukolnik in a noisy and cheerful environment of the puppet “brotherhood” – artists, poets, who pretty much distracted from creativity. Despite this, the work progressed, and other works appeared in parallel – romances based on Pushkin’s poems, the vocal cycle “Farewell to Petersburg” (at the Kukolnik station), the first version of “Fantasy Waltz”, music for the Kukolnik’s drama “Prince Kholmsky”.

Glinka’s activities as a singer and vocal teacher date back to the same time. He writes “Etudes for the Voice”, “Exercises to Improve the Voice”, “School of Singing”. Among his students are S. Gulak-Artemovsky, D. Leonova and others.

The premiere of “Ruslan and Lyudmila” on November 27, 1842 brought Glinka a lot of hard feelings. The aristocratic public, led by the imperial family, met the opera with hostility. And among Glinka’s supporters, opinions were sharply divided. The reasons for the complex attitude to the opera lie in the deeply innovative essence of the work, with which the fairy-tale-epic opera theater, previously unknown to Europe, began, where various musical-figurative spheres appeared in a bizarre interweaving – epic, lyrical, oriental, fantastic. Glinka “sang Pushkin’s poem in an epic way” (B. Asafiev), and the unhurried unfolding of events based on the change of colorful pictures was prompted by Pushkin’s words: “Deeds of bygone days, legends of ancient times.” As a development of Pushkin’s most intimate ideas, other features of the opera appeared in the opera. Sunny music, singing the love of life, faith in the triumph of good over evil, echoes the famous “Long live the sun, let the darkness hide!”, And the bright national style of the opera, as it were, grows out of the lines of the prologue; “There is a Russian spirit, there smells of Russia.” Glinka spent the next few years abroad in Paris (1844-45) and in Spain (1845-47), having specially studied Spanish before the trip. In Paris, a concert of Glinka’s works was held with great success, about which he wrote: “… I the first Russian composer, who introduced the Parisian public to his name and his works written in Russia and for Russia“. Spanish impressions inspired Glinka to create two symphonic pieces: “Jota of Aragon” (1845) and “Memories of a Summer Night in Madrid” (1848-51). Simultaneously with them, in 1848, the famous “Kamarinskaya” appeared – a fantasy on the themes of two Russian songs. Russian symphonic music originates from these works, equally “reported to connoisseurs and ordinary public.”

For the last decade of his life, Glinka lived alternately in Russia (Novospasskoye, St. Petersburg, Smolensk) and abroad (Warsaw, Paris, Berlin). The atmosphere of ever thickening muffled hostility had a depressing effect on him. Only a small circle of true and ardent admirers supported him during these years. Among them are A. Dargomyzhsky, whose friendship began during the production of the opera Ivan Susanin; V. Stasov, A. Serov, young M. Balakirev. Glinka’s creative activity is noticeably declining, but the new trends in Russian art associated with the flourishing of the “natural school” did not pass him by and determined the direction of further artistic searches. He begins work on the program symphony “Taras Bulba” and the opera-drama “Two-wife” (according to A. Shakhovsky, unfinished). At the same time, interest arose in the polyphonic art of the Renaissance, the idea of uXNUMXbuXNUMXbthe possibility of connecting the “Western Fugue with terms of our music the bonds of lawful marriage. This again led Glinka in 1856 to Berlin to Z. Den. A new stage in his creative biography began, which was not destined to end … Glinka did not have time to implement much of what was planned. However, his ideas were developed in the work of Russian composers of subsequent generations, who inscribed on their artistic banner the name of the founder of Russian music.

O. Averyanova