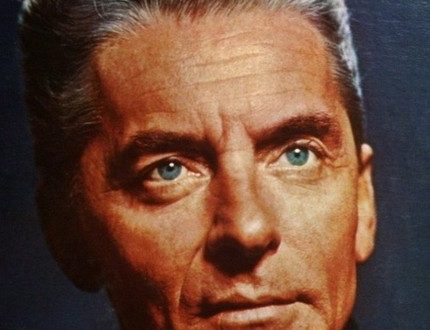

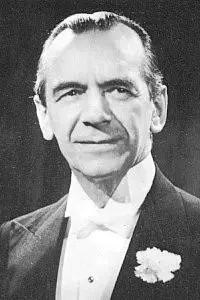

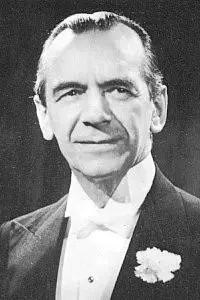

Malcolm Sargent |

Malcolm Sargent

“Small, lean, Sargent, it would seem, does not conduct at all. His movements are stingy. The tips of his long, nervous fingers sometimes express much more with him than a conductor’s baton, he mostly conducts in parallel with both hands, never conducts by heart, but always from the score. How many conductor’s “sins”! And with this seemingly “imperfect” technique, the orchestra always fully understands the slightest intentions of the conductor. The example of Sargent clearly shows what a huge place a clear inner idea of the musical image and the firmness of creative convictions occupy in the conductor’s skill, and what a subordinate, albeit very important place is occupied by the external side of conducting. Such is the portrait of one of the leading English conductors, painted by his Soviet colleague Leo Ginzburg. Soviet listeners could be convinced of the validity of these words during the performances of the artist in our country in 1957 and 1962. The features inherent in his creative appearance are in many respects characteristic of the entire English conducting school, one of the most prominent representatives of which he was for several decades.

Sargent’s conducting career began quite late, although he showed talent and love for music from childhood. After graduating from the Royal College of Music in 1910, Sargent became a church organist. In his spare time, he devoted himself to composition, studied with amateur orchestras and choirs, and studied piano. At that time, he did not seriously think about conducting, but occasionally he had to lead the performance of his own compositions, which were included in London concert programs. The profession of a conductor, according to Sargent’s own admission, “forced him to study Henry Wood.” “I was happy as ever,” adds the artist. Indeed, Sargent found himself. Since the mid-20s, he has regularly performed with orchestras and conducted opera performances, in 1927-1930 he worked with the Russian Ballet of S. Diaghilev, and some time later he was promoted to the ranks of the most prominent English artists. G. Wood wrote then: “From my point of view, this is one of the best modern conductors. I remember, it seems in 1923, he came to me asking for advice – whether to engage in conducting. I heard him conduct his Nocturnes and Scherzos the year before. I had no doubt that he could easily turn into a first-class conductor. And I am pleased to know that I was right in persuading him to leave the piano.

In the post-war years, Sargent became the true successor and successor of Wood’s work as a conductor and educator. Leading the orchestras of the London Philharmonic at the BBC, for many years he led the famous Promenade Concerts, where hundreds of works by composers of all times and peoples were performed under his direction. Following Wood, he introduced the English public to many works by Soviet authors. “As soon as we have a new work by Shostakovich or Khachaturian,” the conductor said, “the orchestra I lead immediately seeks to include it in its program.”

Sargent’s contribution to the popularization of English music is great. No wonder his compatriots called him “the British master of music” and “the ambassador of English art.” All the best that was created by Purcell, Holst, Elgar, Dilius, Vaughan Williams, Walton, Britten, Tippett found a deep interpreter in Sargent. Many of these composers have gained fame outside of England thanks to a remarkable artist who has performed on all continents of the globe.

Sargent’s name gained such wide popularity in England that one of the critics wrote back in 1955: “Even for those who have never been to a concert, Sargent is today a symbol of our music. Sir Malcolm Sargent is not the only conductor in Britain. Many may add that, in their opinion, it is not the best. But few people will undertake to deny that there is no musician in the country who would do more to bring people to music and bring music closer to people. Sargent carried his noble mission as an artist until the end of his life. “As long as I feel enough strength and as long as I am invited to conduct,” he said, “I will work with pleasure. My profession has always brought me satisfaction, brought me to many beautiful countries and gave me lasting and valuable friendship.

L. Grigoriev, J. Platek