Keys in the space of multiplicities

After the Second World War, ethnographers were surprised to find airfields, radio cabins, and even life-size aircraft built by local tribes from bamboo, wood, leaves, vines, and other improvised materials on many islands of the Pacific Ocean.

The solution to such strange structures was soon found. It’s all about the so-called cargo cults. During World War II, the Americans built airfields on the islands to supply the army. Valuable cargo was delivered to the airfields: clothes, canned food, tents and other useful things, some of which were given to local residents in exchange for hospitality, guide services, etc. When the war ended, and the bases were empty, the natives themselves began to build similarities of airfields in the mystical hope that in this way they would again attract cargo (English cargo – cargo).

Of course, with all the similarity to real cars, bamboo planes could not fly, receive radio signals, or deliver cargo.

Just “similar” does not mean “the same”.

Mode and tonality

Similar, but not identical, phenomena are found in music.

For example, the C major called both triad and tonality. As a rule, from the context you can understand what is meant. In addition, the chord in C major and tone in C major are closely related.

There is an example of ingenuity. Key in C major и Ionian mode from to. If you read harmony textbooks, they emphasize that these are different musical systems, one is tonal, the other is modal. But it is not entirely clear what exactly is the difference, except for the name. Indeed, in fact, these are the same 7 notes: do, re, mi, fa, salt, la, si.

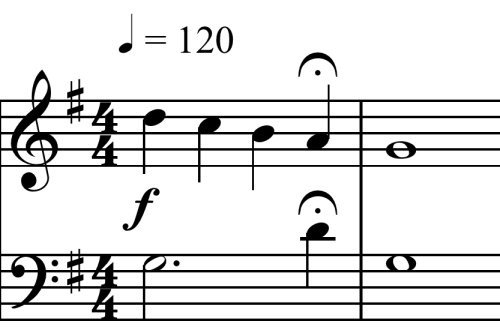

And the scales of these musical systems sound very similar, even if you use Pythagorean notes for the Ionian mode, and natural notes for the major:

Natural C major

Ionian mode from to

In the last article, we analyzed in detail what the old frets are, including the Ionian one. These modes belong to the Pythagorean system, that is, they are built only by multiplying by 2 (octave) and multiplying by 3 (duodecime). In the space of multiplicities (PC), the Ionian mode from to will look like this (Fig. 1).

Now let’s try to figure out what tonality is.

The first and main feature of tonality is, of course, tonic. What is a tonic? It would seem that the answer is obvious: the tonic is the main note, a certain center, a reference point for the entire system.

Let’s look at the first picture. Is it possible to say that in the rectangle of the Ionian fret the note to is the main one? We agree that it is not. We have built this rectangle from to, but we could just as well build it, for example, from F, it would have turned out to be the Lydian mode (Fig. 2).

In other words, the note from which we built the scale has changed, but the entire harmonic structure has remained the same. Moreover, this structure can be built from any sound inside the rectangle (Fig. 3).

How can we get the tonic? How can we centralize a note, make it the main one?

In modal music, “dominance” is usually achieved by temporary constructions. The “main” note sounds more often, the work begins or ends with it, it falls on strong beats.

But there is also a purely harmonic way to “centralize” a note.

If we draw a crosshair (Fig. 4 on the left), then we automatically have a central point.

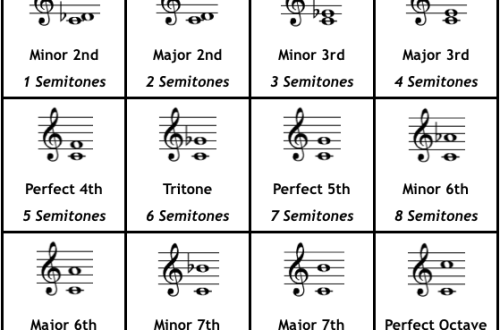

In harmony, the same principle is used, but instead of a crosshair, only a part of it is used – either a corner directed to the right and up, or a corner directed to the left and down (Fig. 4 on the right). Such corners are built in the PC and allow you to harmonically centralize the note. The names of these corners are known not only to musicians – they major и minor (Fig. 5).

By attaching such a corner to any note in the PC, we get a major or minor triad. Both of these constructions “centralize” the note. Moreover, they are mirror images of each other. It is these properties that fixed major and minor in musical practice.

You can notice one unusual feature: the major triad is called by the note, which is located directly in the crosshairs, and the minor by the note located on the left (highlighted in a circle in the diagram in Fig. 5). That is consonance c-is-g, in which the central sound is gIs called C minor by the note in the left beam. In order to mathematically accurately answer the question of why this is so, we would have to resort to rather complicated calculations, in particular, to the calculation of the measure of the consonance of a chord. Instead, let’s try to explain it schematically. In major, on both beams – both fifth and third – we go “up”, in contrast to minor, where movement in both directions is “down”. Thus, the lower sound in a major chord is the central one, and in a minor chord it is the left one. Since the chord is traditionally called by the bass, that is, the lower sound, the minor got its name not by the note in the crosshairs, but by the note in the left beam.

But, we emphasize that something else is important here. Centralization is important, we feel this structure both in major and in minor.

Also note that, unlike the old frets, the tonality uses a tertian (vertical) axis, it is it that allows you to “harmonically” centralize the note.

But no matter how beautiful these chords are, there are only 3 notes in them, and you can’t compose much from 3 notes. What are the considerations for tonality? And again we will consider it from the point of view of harmony, that is, in the PC.

- First, since we managed to centralize the note, we would not want to lose this centralization. This means that it is desirable to build something around this note in a symmetrical way.

- Secondly, we used corners for the chord. This is a fundamentally new structure, which was not in the Pythagorean system. It would be nice to repeat them so that the listener understands that they did not arise by chance, that this is a very important element for us.

From these two considerations, the method of constructing the key follows: we need to repeat the selected corners symmetrically with respect to the “central” note, and it is desirable to do this as close to it as possible (Fig. 6).

This is what the repetition of the corners looks like in the case of a major. The central corner is called tonic, left – subdominant, and the right dominant. The seven notes used in these corners give the scale of the corresponding key. And the structure emphasizes the centralization that we have achieved in the chord. Compare Figure 6 with Figure 1 – here a clear illustration of how tonality differs from mode.

This is what a major scale sounds like, with a TSDT turn at the end.

The minor will be built exactly according to the same principle, only the corner will be with rays not up, but down (Fig. 7).

As you can see, the principle of construction is exactly the same as in the major: three corners (subdominant, tonic and dominant), located symmetrically with respect to the central one.

We can build the same structure not from a note to, but from any other. We get a major or minor key from it.

For example, let’s build a tone you are a minor. We build a minor corner from yours, and then add two corners on the right and left, we get this picture (Fig. 8).

The picture immediately shows which notes form the key, how many signs are in the key at the key, which notes are included in the tonic group, which are in the dominant, which are in the subdominant.

By the way, to the question of key accidentals. In PC, we denoted all notes as sharps, but if desired, of course, they can be written as enharmonic equals with flats. What signs will actually be in the key?

This can be determined quite simply. If a note without a sharp is already included in the key, then you cannot use a sharp – we write down an enharmonic with a flat instead.

It’s easier to understand this with examples. in three corners you are a minor (fig.8) not a note c, no note f are not present, therefore, we can safely place key signs with them. In key in this way we will have notes Are you there и fis, and the tonality will be sharp.

В C minor (Fig. 7) and note g and note d already exists “in its pure form”, therefore, it will not work to use them with sharps either. Conclusion: in this case, we change notes with sharps to notes with flats. Key C minor will be silent.

Types of Major and Minor

Musicians know that in addition to natural there are also special types of major and minor: melodic and harmonic. It is often quite difficult to remember exactly which steps to raise or lower in such keys.

Everything becomes much easier if you understand the structure of these keys, and for this we draw them in a PC (Fig. 9).

To build these types of major and minor, we simply change the left and right corner from major to minor or vice versa. That is, whether the tonality will be major or minor is determined by the central corner, but the extreme ones determine its appearance.

In harmonic major, the left corner (subdominant) changes to minor. In harmonic minor, the right corner (dominant) changes to major.

In melodic keys, both corners – both right and left – change to the opposite of the central one.

Of course, we can build all types of major and minor from any note, their harmonic structure, that is, the way they look in the PC, will not change.

The attentive reader will probably wonder: can we build keys in other ways? What if you change the shape of the corners? Or their symmetry? And should we limit ourselves to “symmetrical” systems?

We will answer these questions in the next article.

Author – Roman Oleinikov

The author expresses his gratitude to the composer Ivan Soshinsky for his help in creating audio materials.