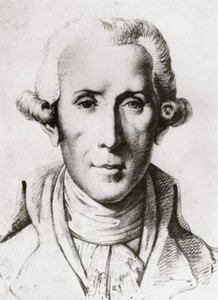

Ivan Evstafievich Khandoshkin |

Ivan Khandoshkin

Russia of the XNUMXth century was a country of contrasts. Asian luxury coexisted with poverty, education – with extreme ignorance, the refined humanism of the first Russian enlighteners – with savagery and serfdom. At the same time, an original Russian culture developed rapidly. At the beginning of the century, Peter I was still cutting the beards of the boyars, overcoming their fierce resistance; in the middle of the century, the Russian nobility spoke elegant French, operas and ballets were staged at the court; the court orchestra, composed of renowned musicians, was considered one of the best in Europe. Famous composers and performers came to Russia, attracted here by generous gifts. And in less than a century, ancient Russia stepped out of the darkness of feudalism to the heights of European education. The layer of this culture was still very thin, but it already covered all areas of social, political, literary and musical life.

The last third of the XNUMXth century is characterized by the appearance of outstanding domestic scientists, writers, composers, and performers. Among them are Lomonosov, Derzhavin, the famous collector of folk songs N. A. Lvov, composers Fomin and Bortnyansky. In this brilliant galaxy, a prominent place belongs to the violinist Ivan Evstafievich Khandoshkin.

In Russia, for the most part, they treated their talents with disdain and distrust. And no matter how famous and loved Khandoshkin was during his lifetime, none of his contemporaries became his biographer. The memory of him almost faded shortly after his death. The first who began to collect information about this extraordinary violin singer was the tireless Russian researcher V. F. Odoevsky. And from his searches, only scattered sheets remained, yet they turned out to be invaluable material for subsequent biographers. Odoevsky still found the contemporaries of the great violinist alive, in particular his wife Elizaveta. Knowing his conscientiousness as a scientist, the materials he collected can be trusted unconditionally.

Patiently, bit by bit, the Soviet researchers G. Fesechko, I. Yampolsky, and B. Volman restored Khandoshkin’s biography. There was a lot of obscure and confused information about the violinist. The exact dates of life and death were not known; it was believed that Khandoshkin came from serfs; according to some sources, he studied with Tartini, according to others, he never left Russia and was never a student of Tartini, etc. And even now, far from everything has been clarified.

With great difficulty, G. Fesechko managed to establish the dates of life and death of Khandoshkin from the church books of burial records of the Volkov cemetery in St. Petersburg. It was believed that Khandoshkin was born in 1765. Fesechko discovered the following entry: “1804, on March 19, the court retired Mumshenok (i.e. Mundshenk. – L.R.) Ivan Evstafiev Khandoshkin died 57 years old from paralysis.” The record testifies that Khandoshkin was born not in 1765, but in 1747 and was buried at the Volkovo cemetery.

From Odoevsky’s notes, we learn that Khandoshkin’s father was a tailor, and besides, a timpani player in the orchestra of Peter III. A number of printed works report that Evstafiy Khandoshkin was Potemkin’s serf, but there is no documentary evidence to confirm this.

It is reliably known that Khandoshkin’s violin teacher was the court musician, the excellent violinist Tito Porto. Most likely Porto was his first and last teacher; the version about a trip to Italy to Tartini is extremely doubtful. Subsequently, Khandoshkin competed with European celebrities who came to St. Petersburg – with Lolly, Schzipem, Sirman-Lombardini, F. Tietz, Viotti, and others. Could it be that when Sirman-Lombardini met with Khandoshkin, it was not noted anywhere that they were Tartini’s fellow students? Undoubtedly, such a talented student, who, moreover, came from such an exotic country in the eyes of Italians as Russia, would not go unnoticed by Tartini. Traces of Tartini’s influences in his compositions do not say anything, since the sonatas of this composer were widely known in Russia.

In his public position, Khandoshkin achieved a lot for his time. In 1762, that is, at the age of 15, he was admitted to the court orchestra, where he worked until 1785, reaching the positions of the first chamber musician and bandmaster. In 1765, he was listed as a teacher in the educational classes of the Academy of Arts. In the classrooms, opened in 1764, along with painting, students were taught subjects from all areas of the arts. They also learned to play musical instruments. Since classes were opened in 1764, Khandoshkin can be considered the Academy’s first violin teacher. A young teacher (he was 17 at the time) had 12 students, but who exactly is unknown.

In 1779, the clever businessman and former breeder Karl Knipper received permission to open the so-called “Free Theater” in St. Petersburg and for this purpose recruit 50 pupils – actors, singers, musicians – from the Moscow Orphanage. According to the contract, they had to work for 3 years without a salary, and over the next three years they were to receive 300-400 rubles a year, but “on their own allowance.” A survey conducted after 3 years revealed a terrible picture of the living conditions of young actors. As a result, a board of trustees was established over the theater, which terminated the contract with Knipper. The talented Russian actor I. Dmitrevsky became the head of the theater. He directed 7 months – from January to July 1783 – after which the theater became state-owned. Leaving the post of director, Dmitrevsky wrote to the board of trustees: “… in the reasoning of the pupils entrusted to me, let me say without praise that I made every effort about their education and moral behavior, in which I refer to them themselves. Their teachers were Mr. Khandoshkin, Rosetti, Manstein, Serkov, Anjolinni, and myself. I leave it to the highly respected Council and the public to judge whose children are more enlightened: whether it is with me at seven months or with my predecessor in three years. It is significant that the name of Khandoshkin is ahead of the rest, and this can hardly be considered accidental.

There is another page of Khandoshkin’s biography that has come down to us – his appointment to the Yekaterinoslav Academy, organized in 1785 by Prince Potemkin. In a letter to Catherine II, he asked: “As at Yekaterinoslav University, where not only sciences, but also arts are taught, there should be a Conservatory for music, then I accept the courage to most humbly ask for the dismissal of the court musician Khandoshkin there with an award for his long-term pension service and with the awarding of the rank of mouthpiece of the courtier. Potemkin’s request was granted and Khandoshkin was sent to the Yekaterinoslav Academy of Music.

On the way to Yekaterinoslav, he lived for some time in Moscow, as evidenced by the announcement in Moskovskie Vedomosti about the publication of two Polish works by Khandoshkin, “living in the 12th part of the first quarter at No. Nekrasov.

According to Fesechko, Khandoshkin left Moscow around March 1787 and organized in Kremenchug something like a conservatory, where there was a male choir of 46 singers and an orchestra of 27 people.

As for the music academy, organized at the Yekaterinoslav University, Sarti was eventually approved instead of Khandoshkin as its director.

The financial situation of the employees of the Academy of Music was extremely difficult, for years they were not paid salaries, and after the death of Potemkin in 1791, appropriations ceased altogether, the academy was closed. But even earlier, Khandoshkin left for St. Petersburg, where he arrived in 1789. Until the end of his life, he no longer left the Russian capital.

The life of an outstanding violinist passed in difficult conditions, despite the recognition of his talent and high positions. In the 10th century, foreigners were patronized, and domestic musicians were treated with disdain. In the imperial theaters, foreigners were entitled to a pension after 20 years of service, Russian actors and musicians – after 1803; foreigners received fabulous salaries (for example, Pierre Rode, who arrived in St. Petersburg in 5000, was invited to serve at the imperial court with a salary of 450 silver rubles a year). The earnings of Russians who held the same positions ranged from 600 to 4000 rubles a year in banknotes. A contemporary and rival of Khandoshkin, the Italian violinist Lolly, received 1100 rubles a year, while Khandoshkin received XNUMX. And this was the highest salary that a Russian musician was entitled to. Russian musicians were usually not allowed into the “first” court orchestra, but were allowed to play in the second – “ballroom”, serving palace amusements. Khandoshkin worked for many years as an accompanist and conductor of the second orchestra.

Need, material difficulties accompanied the violinist throughout his life. In the archives of the directorate of the imperial theaters, his petitions for the issuance of “wood” money, that is, meager amounts for the purchase of fuel, the payment of which was delayed for years, have been preserved.

V. F. Odoevsky describes a scene that eloquently testifies to the living conditions of the violinist: “Khandoshkin came to the crowded market … ragged, and sold a violin for 70 rubles. The merchant told him that he would not give him a loan because he did not know who he was. Khandoshkin named himself. The merchant said to him: “Play, I’ll give you the violin for free.” Shuvalov was in the crowd of people; having heard Khandoshkin, he invited him to his place, but when Khandoshkin noticed that he was being taken to Shuvalov’s house, he said: “I know you, you are Shuvalov, I will not go to you.” And he agreed after much persuasion.

In the 80s, Khandoshkin often gave concerts; he was the first Russian violinist to give open public concerts. On March 10, 1780, his concert was announced in St. Petersburg Vedomosti: “On Thursday, the 12th of this month, a musical concert will be given at the local German theater, in which Mr. Khandoshkin will play a solo on a detuned violinist.”

Khandoshkin’s performing talent was enormous and versatile; he played superbly not only on the violin, but also on the guitar and balalaika, conducted for many years and should be mentioned among the first Russian professional conductors. According to contemporaries, he had a huge tone, unusually expressive and warm, as well as a phenomenal technique. He was a performer of a large concert plan – he performed in theater halls, educational institutions, squares.

His emotionality and sincerity amazed and captured the audience, especially when performing Russian songs: “Listening to Khandoshkin’s Adagio, no one could resist tears, and with indescribably bold jumps and passages, which he performed on his violin with true Russian prowess, the listeners’ feet and the listeners themselves began to bounce.

Khandoshkin impressed with the art of improvisation. Odoevsky’s notes indicate that at one of the evenings at S. S. Yakovlev’s, he improvised 16 variations with the most difficult violin tuning: salt, si, re, salt.

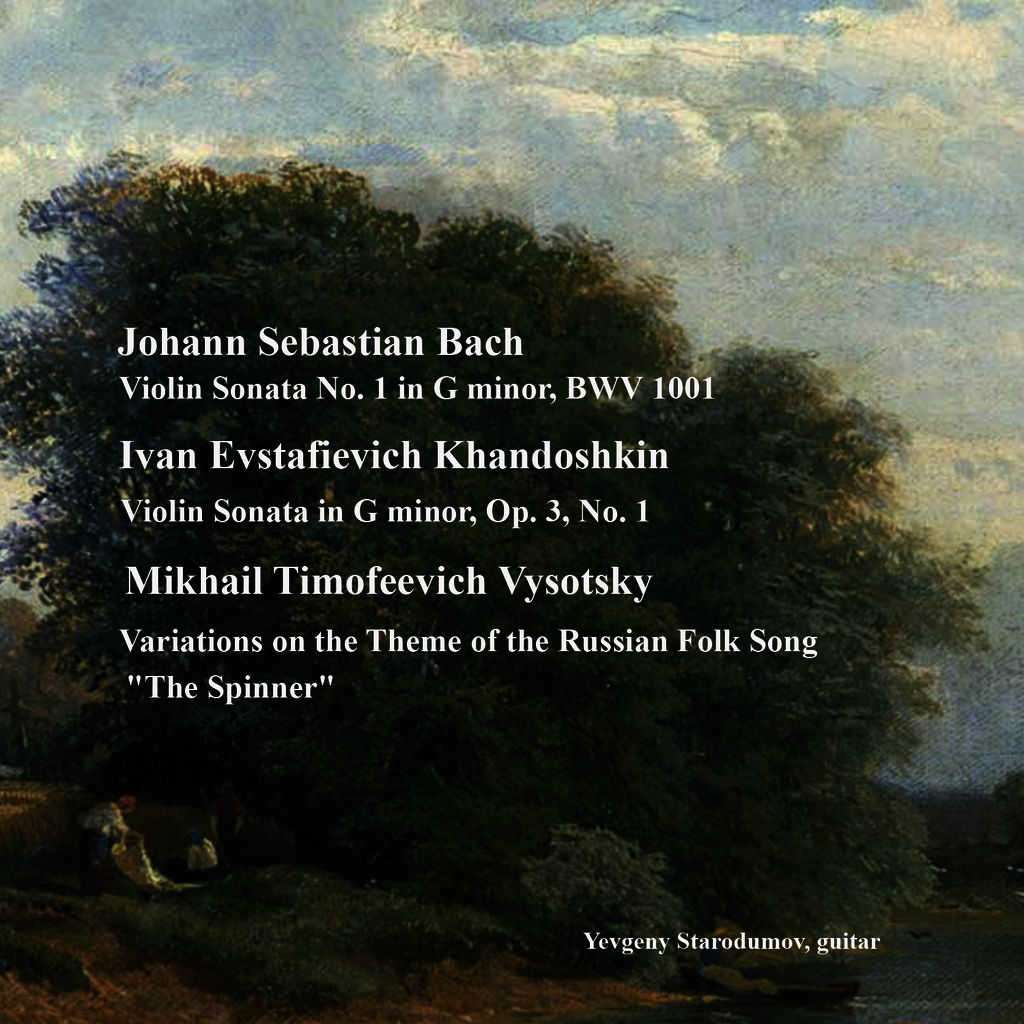

He was an outstanding composer – he wrote sonatas, concertos, variations on Russian songs. Over 100 songs were “put on the violin”, but little has come down to us. Our ancestors treated his heritage with great “racial” indifference, and when they missed it, it turned out that only miserable crumbs were preserved. The concertos have been lost, out of all the sonatas there are only 4, and a half or two dozen variations on Russian songs, that’s all. But even from them one can judge Khandoshkin’s spiritual generosity and musical talent.

Processing the Russian song, Khandoshkin lovingly finished each variation, decorating the melody with intricate ornaments, like a Palekh master in his box. The lyrics of the variations, light, wide, songlike, had the source of rural folklore. And in a popular way, his work was improvisational.

As for the sonatas, their stylistic orientation is very complex. Khandoshkin worked during the period of rapid formation of Russian professional music, the development of its national forms. This time was also controversial for Russian art in relation to the struggle of styles and trends. The artistic tendencies of the outgoing XNUMXth century with its characteristic classical style still lived on. At the same time, elements of the coming sentimentalism and romanticism were already accumulating. All this is bizarrely intertwined in the works of Khandoshkin. In his most famous unaccompanied Violin Sonata in G minor, movement I, characterized by sublime pathos, seems to have been created in the era of Corelli – Tartini, while the exuberant dynamics of the allegro, written in sonata form, is an example of pathetic classicism. In some variations of the finale, Khandoshkin can be called the forerunner of Paganini. Numerous associations with him in Khandoshkin are also noted by I. Yampolsky in the book “Russian Violin Art”.

In 1950 Khandoshkin’s Viola Concerto was published. However, there is no autograph of the concerto, and in terms of style, much in it makes one doubt whether Khandoshkin is really its author. But if, nevertheless, the Concerto belongs to him, then one can only marvel at the closeness of the middle part of this work to the elegiac style of Alyabyev-Glinka. Khandoshkin in it seemed to have stepped over two decades, opening the sphere of elegiac imagery, which was most characteristic of Russian music in the first half of the XNUMXth century.

One way or another, but the work of Khandoshkin is of exceptional interest. It, as it were, throws a bridge from the XNUMXth to the XNUMXth century, reflecting the artistic trends of its era with extraordinary clarity.

L. Raaben