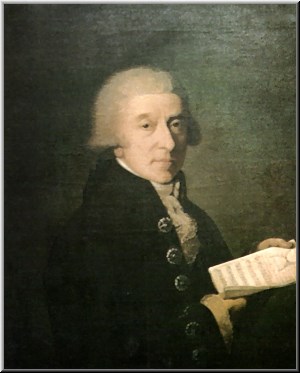

Giuseppe Sarti |

Giuseppe Sarti

The famous Italian composer, conductor and teacher G. Sarti made a significant contribution to the development of Russian musical culture.

He was born in the family of a jeweler – an amateur violinist. He received his primary musical education at a church singing school, and later took lessons from professional musicians (from F. Vallotti in Padua and from the famous Padre Martini in Bologna). By the age of 13, Sarti already played keyboards quite well, which allowed him to take the position of organist in his hometown. Since 1752, Sarti began to work in the opera house. His first opera, Pompey in Armenia, was met with great enthusiasm, and his second, written for Venice, The Shepherd King, brought him real triumph and fame. In the same year, 1753, Sarti was invited to Copenhagen as bandmaster of an Italian opera troupe and began composing, along with Italian operas, singspiel in Danish. (It is noteworthy that, having lived in Denmark for about 20 years, the composer never learned Danish, using interlinear translation when composing.) During his years in Copenhagen, Sarti created 24 operas. It is believed that Sarti’s work laid the foundation for Danish opera in many ways.

Along with writing, Sarti was engaged in pedagogical activities. At one time he even gave singing lessons to the Danish king. In 1772, the Italian entreprise collapsed, the composer had a large debt, and in 1775, by a court verdict, he was forced to leave Denmark. In the next decade, Sarti’s life was connected mainly with two cities in Italy: Venice (1775-79), where he was the director of the women’s conservatory, and Milan (1779-84), where Sarti was the conductor of the cathedral. The composer’s work during this period reaches European fame – his operas are staged on the stages of Vienna, Paris, London (among them – “Village Jealousy” – 1776, “Achilles on Skyros” – 1779, “Two quarrel – the third rejoices” – 1782). In 1784, at the invitation of Catherine II, Sarti arrived in Russia. On the way to St. Petersburg, in Vienna, he met W. A. Mozart, who carefully studied his compositions. Subsequently, Mozart used one of Sarti’s operatic themes in the Don Juan ball scene. For his part, not appreciating the genius of the composer, or perhaps secretly jealous of Mozart’s talent, a year later Sarti published a critical article about his quartets.

Occupying the position of court bandmaster in Russia, Sarti created 8 operas, a ballet and about 30 works of the vocal and choral genre. Sarti’s success as a composer in Russia was accompanied by the success of his court career. The first years after his arrival (1786-90) he spent in the south of the country, being in the service of G. Potemkin. The prince had ideas about organizing a music academy in the city of Yekaterinoslav, and Sarti then received the title of director of the academy. A curious petition from Sarti to send him money for the establishment of the academy, as well as to grant the promised village, as his “personal economy is in an extremely precarious state,” has been preserved in the Moscow archives. From the same letter one can also judge the composer’s future plans: “If I had a military rank and money, I would ask the government to give me land, I would call the Italian peasants and build houses on this land.” Potemkin’s plans were not destined to come true, and in 1790 Sarti returned to St. Petersburg to the duties of court bandmaster. By order of Catherine II, together with K. Canobbio and V. Pashkevich, he took part in the creation and staging of a grandiose performance based on the text of the Empress with a freely interpreted plot from Russian history – Oleg’s Initial Administration (1790). After the death of Catherine Sarti, he wrote a solemn choir for the coronation of Paul I, thus retaining his privileged position at the new court.

The last years of his life, the composer was engaged in theoretical research on acoustics and, among other things, set the frequency of the so-called. “Petersburg tuning fork” (a1 = 436 Hz). The St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences highly appreciated Sarti’s scientific works and elected him an honorary member (1796). Sarti’s acoustic research retained its significance for almost 100 years (only in 1885 in Vienna was the international standard a1 = 435 Hz approved). In 1802, Sarti decided to return to his homeland, but on the way he fell ill and died in Berlin.

Creativity Sarti in Russia, as it were, completes a whole era of creativity of Italian musicians invited throughout the 300th century. Petersburg as a court bandmaster. Cantatas and oratorios, Sarti’s salutatory choirs and hymns formed a special page in the development of Russian choral culture in the Catherine era. With their scale, monumentality and grandiosity of sound, pomp of orchestral coloring, they perfectly reflected the tastes of the St. Petersburg aristocratic circle of the last third of the 1792th century. The works were created by order of the court, were dedicated to the major victories of the Russian army or to the solemn events of the imperial family, and were usually performed in the open air. Sometimes the total number of musicians reached 2 people. So, for example, when performing the oratorio “Glory to God in the Highest” (2) at the end of the Russian-Turkish war, 1789 choirs, 1790 members of the symphony orchestra, a horn orchestra, a special group of percussion instruments were used, bell ringing and cannon fire (!) . Other works of the oratorio genre were distinguished by similar monumentality – “We praise God to you” (on the occasion of the capture of Ochakov, XNUMX), Te Deum (on the capture of the Kiliya fortress, XNUMX), etc.

Sarti’s pedagogical activity, which began in Italy (his student – L. Cherubini), unfolded in full force precisely in Russia, where Sarti created his own school of composition. Among his students are S. Degtyarev, S. Davydov, L. Gurilev, A. Vedel, D. Kashin.

In terms of their artistic significance, Sarti’s works are unequal – approaching the reformist works of K. V. Gluck in some operas, the composer in most of his works still remained faithful to the traditional language of the era. At the same time, welcoming choirs and monumental cantatas, written mainly for Russia, served as models for Russian composers for a long time, without losing their significance in subsequent decades, and were performed at ceremonies and festivities until the coronation of Nicholas I (1826).

A. Lebedeva