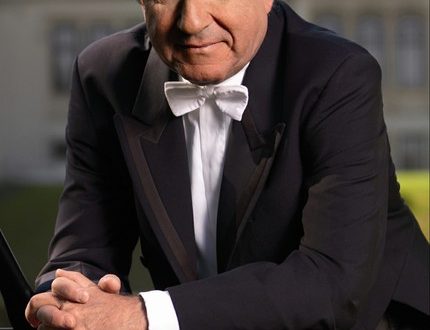

Emil Grigorievich Gilels |

Emil Gilels

One of the prominent music critics once said that it would be pointless to discuss the topic – who is the first, who is the second, who is the third among contemporary Soviet pianists. The table of ranks in art is more than a dubious matter, this critic reasoned; artistic sympathies and tastes of people are different: some may like such and such a performer, others will give preference to such and such… art causes the greatest public outcry, enjoys the most common recognition in a wide circle of listeners” (Kogan G.M. Questions of pianism.—M., 1968, p. 376.). Such a formulation of the question must be recognized, apparently, as the only correct one. If, following the logic of the critic, one of the first to speak of performers, whose art enjoyed the most “general” recognition for several decades, caused “the greatest public outcry,” E. Gilels should undoubtedly be named one of the first.

The work of Gilels is justly referred to as the highest achievement of pianism of the 1957th century. They are attributed both in our country, where each meeting with an artist turned into an event of a large cultural scale, and abroad. The world press has repeatedly and unambiguously spoken out on this score. “There are many talented pianists in the world and a few great masters who tower over everyone. Emil Gilels is one of them…” (“Humanite”, 27, June 1957). “Piano titans like Gilels are born once in a century” (“Mainiti Shimbun”, 22, October XNUMX). These are some, far from the most expansive of the statements about Gilels by foreign reviewers …

If you need piano sheet music, look it up on the Notestore.

Emil Grigoryevich Gilels was born in Odessa. Neither his father nor mother were professional musicians, but the family loved music. There was a piano in the house, and this circumstance, as often happens, played an important role in the fate of the future artist.

“As a child, I didn’t sleep much,” Gilels later said. “At night, when everything was already quiet, I took out my father’s ruler from under the pillow and began to conduct. The small dark nursery was transformed into a dazzling concert hall. Standing on the stage, I felt the breath of a huge crowd behind me, and the orchestra stood waiting in front of me. I raise the conductor’s baton and the air is filled with beautiful sounds. The sounds are getting louder and louder. Forte, fortissimo! … But then the door usually opened a little, and the alarmed mother interrupted the concert at the most interesting place: “Are you waving your arms again and eating at night instead of sleeping?” Have you taken the line again? Now give it back and go to sleep in two minutes!” (Gilels E.G. My dreams came true!//Musical life. 1986. No. 19. P. 17.)

When the boy was about five years old, he was taken to the teacher of the Odessa Music College, Yakov Isaakovich Tkach. He was an educated, knowledgeable musician, a pupil of the famous Raul Pugno. Judging by the memoirs that have been preserved about him, he is an erudite in terms of various editions of the piano repertoire. And one more thing: a staunch supporter of the German school of etudes. At Tkach, young Gilels went through many opuses by Leshgorn, Bertini, Moshkovsky; this laid the strongest foundation of his technique. The weaver was strict and exacting in his studies; From the very beginning, Gilels was accustomed to work – regular, well-organized, not knowing any concessions or indulgences.

“I remember my first performance,” Gilels continued. “A seven-year-old student of the Odessa Music School, I went up to the stage to play Mozart’s C major sonata. Parents and teachers sat behind in solemn expectation. The famous composer Grechaninov came to the school concert. Everyone was holding real printed programs in their hands. On the program, which I saw for the first time in my life, it was printed: “Mozart’s Sonata Spanish. Mile Gilels. I decided that “sp.” – it means Spanish and was very surprised. I’ve finished playing. The piano was right next to the window. Beautiful birds flew to the tree outside the window. Forgetting that this was a stage, I began to look at the birds with great interest. Then they approached me and quietly offered to leave the stage as soon as possible. I reluctantly left, looking out the window. This is how my first performance ended. (Gilels E.G. My dreams came true!//Musical life. 1986. No. 19. P. 17.).

At the age of 13, Gilels enters the class of Berta Mikhailovna Reingbald. Here he replays a huge amount of music, learns a lot of new things – and not only in the field of piano literature, but also in other genres: opera, symphony. Reingbald introduces the young man to the circles of the Odessa intelligentsia, introduces him to a number of interesting people. Love comes to the theater, to books – Gogol, O’Henry, Dostoevsky; the spiritual life of a young musician becomes every year richer, richer, more diverse. A man of great inner culture, one of the best teachers who worked at the Odessa Conservatory in those years, Reingbald helped her student a lot. She brought him close to what he most needed. Most importantly, she attached herself to him with all her heart; it would not be an exaggeration to say that neither before nor after her, Gilels the student met this attitude towards himself … He retained a feeling of deep gratitude to Reingbald forever.

And soon fame came to him. The year 1933 came, the First All-Union Competition of Performing Musicians was announced in the capital. Going to Moscow, Gilels did not rely too much on luck. What happened came as a complete surprise to himself, to Reingbald, to everyone else. One of the pianist’s biographers, returning to the distant days of Gilels’ competitive debut, paints the following picture:

“The appearance of a gloomy young man on the stage went unnoticed. He approached the piano in a businesslike manner, raised his hands, hesitated, and, stubbornly pursing his lips, began to play. The hall was worried. It became so quiet that it seemed that people were frozen in immobility. Eyes turned to the stage. And from there came a mighty current, capturing the listeners and forcing them to obey the performer. The tension grew. It was impossible to resist this force, and after the final sounds of the Marriage of Figaro, everyone rushed to the stage. The rules have been broken. The audience applauded. The jury applauded. Strangers shared their delight with each other. Many had tears of joy in their eyes. And only one person stood imperturbably and calmly, although everything worried him – it was the performer himself. (Khentova S. Emil Gilels. – M., 1967. P. 6.).

The success was complete and unconditional. The impression of meeting a teenager from Odessa resembled, as they said at that time, the impression of an exploding bomb. Newspapers were full of his photographs, the radio spread the news about him to all corners of the Motherland. And then say: first pianist who won first in the history of the country competition of creative youth. However, Gilels’ triumphs did not end there. Three more years have passed – and he has the second prize at the International Competition in Vienna. Then – a gold medal at the most difficult competition in Brussels (1938). The current generation of performers is accustomed to frequent competitive battles, now you can’t surprise with laureate regalia, titles, laurel wreaths of various merits. Before the war it was different. Fewer contests were held, victories meant more.

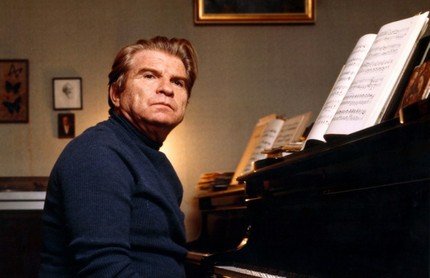

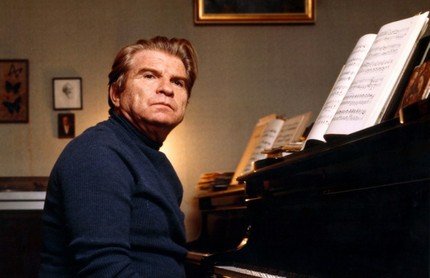

In the biographies of prominent artists, one sign is often emphasized, the constant evolution in creativity, the unstoppable movement forward. A talent of a lower rank sooner or later is fixed at certain milestones, a talent of a large scale does not linger for a long time on any of them. “The biography of Gilels…,” once wrote G. G. Neuhaus, who supervised the young man’s studies at the School of Excellence at the Moscow Conservatory (1935-1938), “is remarkable for its steady, consistent line of growth and development. Many, even very talented pianists, get stuck at some point, beyond which there is no particular movement (upward movement!) The reverse is with Gilels. From year to year, from concert to concert, his performance flourishes, enriches, improves” (Neigauz G. G. The Art of Emil Gilels // Reflections, Memoirs, Diaries. P. 267.).

This was the case at the beginning of Gilels’ artistic path, and the same was preserved in the future, right up to the last stage of his activity. On it, by the way, it is necessary to stop especially, to consider it in more detail. First, it is extremely interesting in itself. Secondly, it is relatively less covered in the press than the previous ones. Musical criticism, previously so attentive to Gilels, in the late seventies and early eighties did not seem to keep up with the pianist’s artistic evolution.

So, what was characteristic of him during this period? That which finds perhaps its most complete expression in the term conceptuality. Extremely clear identification of the artistic and intellectual concept in the performed work: its “subtext”, the leading figurative and poetic idea. The primacy of the internal over the external, the meaningful over the technically formal in the process of making music. It is no secret that conceptuality in the true sense of the word is the one that Goethe had in mind when he claimed that all in a work of art is determined, ultimately, by the depth and spiritual value of the concept, a rather rare phenomenon in musical performance. Strictly speaking, it is characteristic only of achievements of the highest order, such as the work of Gilels, in which everywhere, from a piano concerto to a miniature for one and a half to two minutes of sound, a serious, capacious, psychologically condensed interpretive idea is in the foreground.

Once Gilels gave excellent concerts; his game amazed and captured with technical power; telling the truth the material here noticeably prevailed over the spiritual. What was, was. Subsequent meetings with him I would like to attribute, rather, to a kind of conversation about music. Conversations with the maestro, who is wise with vast experience in performing activities, is enriched by many years of artistic reflections that have become more and more complicated over the years, which ultimately gave special weight to his statements and judgments as an interpreter. Most likely, the artist’s feelings were far from spontaneity and straightforward openness (he, however, was always concise and restrained in his emotional revelations); but they had a capacity, and a rich scale of overtones, and hidden, as if compressed, inner strength.

This made itself felt in almost every issue of Gilels’ extensive repertoire. But, perhaps, the emotional world of the pianist was seen most clearly in his Mozart. In contrast to the lightness, grace, carefree playfulness, coquettish grace and other accessories of the “gallant style” that became familiar when interpreting Mozart’s compositions, something immeasurably more serious and significant dominated in Gilels’ versions of these compositions. Quiet, but very intelligible, scantly clear pianistic reprimand; slowed down, at times emphatically slow tempos (this technique, by the way, was used more and more effectively by the pianist); majestic, confident, imbued with great dignity performing manners – as a result, the general tone, not quite usual, as they said, for the traditional interpretation: emotional and psychological tension, electrification, spiritual concentration … “Perhaps history deceives us: is Mozart a rococo ? – the foreign press wrote, not without a share of pomp, after the performances of Gilels in the homeland of the great composer. – Maybe we pay too much attention to costumes, decorations, jewelry and hairstyles? Emil Gilels made us think about many traditional and familiar things” (Schumann Karl. South German newspaper. 1970. 31 Jan.). Indeed, Gilels’ Mozart – whether it be the Twenty-seventh or Twenty-eighth Piano Concertos, the Third or Eighth Sonatas, the D-minor Fantasy or the F-major variations on a theme by Paisiello (The works most frequently featured on Gilels’ Mozart poster in the seventies.) – did not awaken the slightest association with artistic values a la Lancre, Boucher and so on. The pianist’s vision of the sound poetics of the author of the Requiem was akin to what once inspired Auguste Rodin, the author of the well-known sculptural portrait of the composer: the same emphasis on Mozart’s introspection, Mozart’s conflict and drama, sometimes hidden behind a charming smile, Mozart’s hidden sadness.

Such spiritual disposition, “tonality” of feelings was generally close to Gilels. Like every major, non-standard feeling artist, he had his emotional coloring, which imparted a characteristic, individual-personal coloring to the sound pictures he created. In this coloring, strict, twilight-darkened tones slipped more and more clearly over the years, severity and masculinity became more and more noticeable, awakening vague reminiscences – if we continue analogies with the fine arts – associated with the works of old Spanish masters, painters of the Morales, Ribalta, Ribera schools. , Velasquez… (One of the foreign critics once expressed the opinion that “in the pianist’s playing one can always feel something from la grande tristezza – great sadness, as Dante called this feeling.”) Such, for example, are Gilels’s Third and Fourth piano Beethoven’s concertos, his own sonatas, Twelfth and Twenty-sixth, “Pathétique” and “Appassionata”, “Lunar”, and Twenty-seventh; such are the ballads, op. 10 and Fantasia, Op. 116 Brahms, instrumental lyrics by Schubert and Grieg, plays by Medtner, Rachmaninov and much more. The works that accompanied the artist throughout a significant part of his creative biography clearly demonstrated the metamorphoses that took place over the years in Gilels’s poetic worldview; sometimes it seemed that a mournful reflection seemed to fall on their pages …

The stage style of the artist, the style of the “late” Gilels, has also undergone changes over time. Let us turn, for example, to old critical reports, recall what the pianist once had – in his younger years. There was, according to the testimony of those who heard him, “the masonry of wide and strong constructions”, there was a “mathematical verified strong, steel blow”, combined with “elemental power and stunning pressure”; there was the game of a “genuine piano athlete”, “the jubilant dynamics of a virtuoso festival” (G. Kogan, A. Alschwang, M. Grinberg, etc.). Then something else came. The “steel” of Gilels’s finger strike became less and less noticeable, the “spontaneous” began to be taken under control more and more strictly, the artist moved further and further away from the piano “athleticism”. Yes, and the term “jubilation” has become, perhaps, not the most suitable for defining his art. Some bravura, virtuoso pieces sounded more like Gilels anti-virtuoso – for example, Liszt’s Second Rhapsody, or the famous G minor, Op. 23, a prelude by Rachmaninov, or Schumann’s Toccata (all of which were often performed by Emil Grigorievich on his clavirabends in the mid and late seventies). Pompous with a huge number of concert-goers, in Gilels’ transmission this music turned out to be devoid of even a shadow of pianistic dashing, pop bravado. His game here – as elsewhere – looked a little muted in colors, was technically elegant; movement was deliberately restrained, speeds were moderated – all this made it possible to enjoy the pianist’s sound, rare beautiful and perfect.

Increasingly, the attention of the public in the seventies and eighties was riveted on Gilels’s clavirabends to slow, concentrated, in-depth episodes of his works, to music imbued with reflection, contemplation, and philosophical immersion in oneself. The listener experienced here perhaps the most exciting sensations: he clearly enter I saw a lively, open, intense pulsation of the performer’s musical thought. One could see the “beating” of this thought, its unfolding in sound space and time. Something similar, probably, could be experienced, following the work of the artist in his studio, watching the sculptor transforming a block of marble with his chisel into an expressive sculptural portrait. Gilels involved the audience in the very process of sculpting a sound image, forcing them to feel together with themselves the most subtle and complex vicissitudes of this process. Here is one of the most characteristic signs of his performance. “To be not only a witness, but also a participant in that extraordinary holiday, which is called a creative experience, an artist’s inspiration — what can give the viewer greater spiritual pleasure?” (Zakhava B.E. The skill of the actor and director. – M., 1937. P. 19.) – said the famous Soviet director and theater figure B. Zakhava. Whether to the spectator, the visitor of the concert hall, isn’t everything the same? To be an accomplice in the celebration of Gilels’ creative insights meant to experience really high spiritual joys.

And about one more thing in the pianism of the “late” Gilels. His sound canvases were the very integrity, compactness, inner unity. At the same time, it was impossible not to pay attention to the subtle, truly jewelry dressing of “little things”. Gilels was always famous for the first (monolithic forms); in the second he achieved great skill precisely in the last one and a half to two decades.

Its melodic reliefs and contours were distinguished by a special filigree workmanship. Each intonation was elegantly and accurately outlined, extremely sharp in its edges, clearly “visible” to the public. The smallest motive twists, cells, links – everything was imbued with expressiveness. “Already the way Gilels presented this first phrase is enough to place him among the greatest pianists of our time,” wrote one of the foreign critics. This refers to the opening phrase of one of Mozart’s sonatas played by the pianist in Salzburg in 1970; with the same reason, the reviewer could refer to the phrasing in any of the works that appeared then in the list performed by Gilels.

It is known that every major concert performer intones music in his own way. Igumnov and Feinberg, Goldenweiser and Neuhaus, Oborin and Ginzburg “pronounced” the musical text in different ways. The intonation style of Gilels the pianist was sometimes associated with his peculiar and characteristic colloquial speech: stinginess and accuracy in the selection of expressive material, laconic style, disregard for external beauties; in every word – weight, significance, categoricalness, will …

Everyone who managed to attend the last performances of Gilels will surely remember them forever. “Symphonic Studies” and Four Pieces, Op. 32 Schumann, Fantasies, Op. 116 and Brahms’ Variations on a Theme of Paganini, Song Without Words in A flat major (“Duet”) and Etude in A minor by Mendelssohn, Five Preludes, Op. 74 and Scriabin’s Third Sonata, Beethoven’s Twenty-ninth Sonata and Prokofiev’s Third – all this is unlikely to be erased in the memory of those who heard Emil Grigorievich in the early eighties.

It is impossible not to pay attention, looking at the above list, that Gilels, despite his very middle age, included extremely difficult compositions in his programs – only Brahms’ Variations are worth something. Or Beethoven’s Twenty-Ninth… But he could, as they say, make his life easier by playing something simpler, not so responsible, technically less risky. But, firstly, he never made anything easier for himself in creative matters; it was not in his rules. And secondly: Gilels was very proud; at the time of their triumphs – even more so. For him, apparently, it was important to show and prove that his excellent pianistic technique did not pass over the years. That he remained the same Gilels as he was known before. Basically, it was. And some technical flaws and failures that happened to the pianist in his declining years did not change the overall picture.

… The art of Emil Grigorievich Gilels was a large and complex phenomenon. It is not surprising that it sometimes evoked diverse and unequal reactions. (V. Sofronitsky once spoke about his profession: only that in it has a price that is debatable – and he was right.) during the game, surprise, sometimes disagreement with some decisions of E. Gilels […] paradoxically give way after the concert to the deepest satisfaction. Everything falls into place” (Concert review: 1984, February-March / / Soviet music. 1984. No. 7. P. 89.). The observation is correct. Indeed, in the end, everything fell into place “in its place” … For the work of Gilels had a tremendous power of artistic suggestion, it was always truthful and in everything. And there can be no other real art! After all, in Chekhov’s wonderful words, “it’s especially and good that you can’t lie in it … You can lie in love, in politics, in medicine, you can deceive people and the Lord God himself … – but you can’t deceive in art … “

G. Tsypin