Bedrich Smetana |

Contents

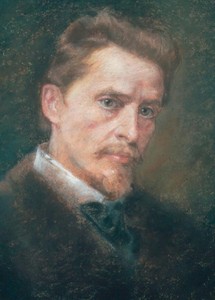

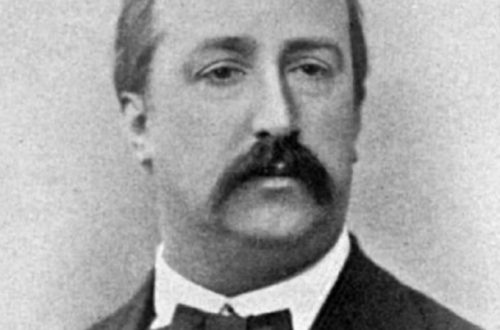

Bedřich Smetana

Sour cream. “The Bartered Bride” Polka (orchestra conducted by T. Beecham)

The many-sided activity of B. Smetana was subordinated to a single goal – the creation of professional Czech music. An outstanding composer, conductor, teacher, pianist, critic, musical and public figure, Smetana performed at a time when the Czech people recognized themselves as a nation with their own, original culture, actively opposing Austrian domination in the political and spiritual sphere.

The love of Czechs for music has been known since ancient times. Hussite liberation movement of the 5th century. spawned martial songs-hymns; in the 6th century, Czech composers made a significant contribution to the development of classical music in Western Europe. Home music-making – solo violin and ensemble playing – has become a characteristic feature of the life of the common people. They also loved music in the family of Smetana’s father, a brewer by profession. From the age of XNUMX, the future composer played the violin, and at XNUMX he publicly performed as a pianist. In his school years, the boy enthusiastically plays in the orchestra, begins to compose. Smetana completes his musical and theoretical education at the Prague Conservatory under the guidance of I. Proksh, at the same time he improves his piano playing.

By the same time (40s), Smetana met R. Schumann, G. Berlioz and F. Liszt, who were on tour in Prague. Subsequently, Liszt would highly appreciate the works of the Czech composer and support him. Being at the beginning of his career under the influence of the romantics (Schumann and F. Chopin), Smetana wrote a lot of piano music, especially in the miniature genre: polkas, bagatelles, impromptu.

The events of the revolution of 1848, in which Smetana happened to take part, found a lively response in his heroic songs (“Song of Freedom”) and marches. At the same time, the pedagogical activity of Smetana began in the school he opened. However, the defeat of the revolution led to an increase in reaction in the policy of the Austrian Empire, which stifled everything Czech. The persecution of leading figures created enormous difficulties in the path of Smetana’s patriotic undertakings and forced him to emigrate to Sweden. He settled in Gothenburg (1856-61).

Like Chopin, who captured the image of a distant homeland in his mazurkas, Smetana writes “Memories of the Czech Republic in the form of poles” for piano. Then he turns to the genre of the symphonic poem. Following Liszt, Smetana uses plots from European literary classics – W. Shakespeare (“Richard III”), F. Schiller (“Wallenstein’s Camp”), Danish writer A. Helenschleger (“Hakon Jarl”). In Gothenburg, Smetana acts as a conductor of the Society of Classical Music, a pianist, and is engaged in teaching activities.

60s – the time of a new upsurge of the national movement in the Czech Republic, and the composer who returned to his homeland is actively involved in public life. Smetana became the founder of the Czech classical opera. Even for the opening of a theater where singers could sing in their native language, a stubborn struggle had to be endured. In 1862, on the initiative of Smetana, the Provisional Theater was opened, where for many years he worked as a conductor (1866-74) and staged his operas.

Smetana’s operatic work is exceptionally diverse in terms of themes and genres. The first opera, The Brandenburgers in the Czech Republic (1863), tells about the struggle against the German conquerors in the 1866th century, the events of distant antiquity here directly echoed with the present. Following the historical-heroic opera, Smetana writes the merry comedy The Bartered Bride (1868), his most famous and extremely popular work. The inexhaustible humour, love of life, song-and-dance nature of the music distinguish it even among the comic operas of the second half of the XNUMXth century. The next opera, Dalibor (XNUMX), is a heroic tragedy written on the basis of an old legend about a knight imprisoned in a tower for sympathy and patronage of the rebellious people, and his beloved Milada, who dies trying to save Dalibor.

On Smetana’s initiative, a nationwide fundraiser was held for the construction of the National Theatre, which opened in 1881 with the premiere of his new opera Libuse (1872). This is an epic about the legendary founder of Prague, Libuse, about the Czech people. The composer called it “a solemn picture.” And now in Czechoslovakia there is a tradition of performing this opera on national holidays, especially significant events. After “Libushe” Smetana writes mainly comic operas: “Two widows”, “Kiss”, “Mystery”. As an opera conductor, he promotes not only Czech but also foreign music, especially the new Slavic schools (M. Glinka, S. Moniuszko). M. Balakirev was invited from Russia to stage Glinka’s operas in Prague.

Smetana became the creator of not only the national classical opera, but also the symphony. More than a symphony, he is attracted by a program symphonic poem. The highest achievement of Smetana in orchestral music is created in the 70s. cycle of symphonic poems “My Motherland” – an epic about the Czech land, its people, history. The poem “Vysehrad” (Vysehrad is an old part of Prague, “the capital city of the princes and kings of the Czech Republic”) is a legend about the heroic past and the past greatness of the motherland.

Romantically colorful music in the poems “Vltava, From Czech fields and forests” draws pictures of nature, free expanses of native land, through which the sounds of songs and dances are carried. In “Sharka” old traditions and legends come to life. “Tabor” and “Blanik” talk about the Hussite heroes, sing “the glory of the Czech land.”

The theme of the homeland is also embodied in chamber piano music: “Czech Dances” is a collection of pictures of folk life, containing the whole variety of dance genres in the Czech Republic (polka, skochna, furiant, coysedka, etc.).

Smetana’s composing music has always been combined with intense and versatile social activities – especially during his life in Prague (60s – first half of the 70s). Thus, the leadership of the Verb of Prague Choral Society contributed to the creation of many works for the choir (including the dramatic poem about Jan Hus, The Three Horsemen). Smetana is a member of the Association of Prominent Figures of Czech Culture “Handy Beseda” and heads its musical section.

The composer was one of the founders of the Philharmonic Society, which contributed to the musical education of the people, acquaintance with the classics and novelties of domestic music, as well as the Czech vocal school, in which he himself studied with singers. Finally, Smetana works as a music critic and continues to perform as a virtuoso pianist. Only a severe nervous illness and hearing loss (1874) forced the composer to give up work at the opera house and limited the scope of his social activities.

Smetana left Prague and settled in the village of Jabkenice. However, he continues to compose a lot (completes the cycle “My Motherland”, writes the latest operas). As before (back in the years of Swedish emigration, the grief over the death of his wife and daughter resulted in a piano trio), Smetana embodies her personal experiences in chamber-instrumental genres. The quartet “From My Life” (1876) is created – a story about one’s own fate, inseparable from the fate of Czech art. Each part of the quartet has a program explanation by the author. Hopeful youth, readiness “to fight in life”, memories of fun days, dances and musical improvisations in salons, a poetic feeling of first love and, finally, “joy at looking at the path traveled in national art”. But everything is drowned out by a monotonous high-pitched sound – like an ominous warning.

In addition to the already mentioned works of the last decade, Smetana writes the opera The Devil’s Wall, the symphonic suite The Prague Carnival, and begins work on the opera Viola (based on Shakespeare’s comedy Twelfth Night), which was prevented from finishing by the growing illness. The difficult state of the composer in recent years was brightened up by the recognition of his work by the Czech people, to whom he dedicated his work.

K. Zenkin

Smetana asserted and passionately defended high national artistic ideals in difficult social conditions, in a life full of drama. As a brilliant composer, pianist, conductor and musical and public figure, he devoted all his vigorous activity to the glorification of his native people.

The life of Smetana is a creative feat. He possessed an indomitable will and perseverance in achieving his goal, and despite all the hardships of life, he managed to fully realize his plans. And these plans were subordinated to one main idea – to help the Czech people with music in their heroic struggle for freedom and independence, to instill in them a sense of vigor and optimism, faith in the final victory of a just cause.

Smetana coped with this difficult, responsible task, because he was in the thick of life, actively responding to the socio-cultural demands of our time. With his work, as well as social activities, he contributed to an unprecedented flourishing not only of the musical, but more broadly – of the entire artistic culture of the motherland. That is why the name Smetana is sacred to the Czechs, and his music, like a battle banner, evokes a legitimate sense of national pride.

The genius of Smetana was not revealed immediately, but gradually matured. The revolution of 1848 helped him realize his social and artistic ideals. Beginning in the 1860s, on the threshold of Smetana’s fortieth birthday, his activities took on an unusually wide scope: he led symphony concerts in Prague as a conductor, directed an opera house, performed as a pianist, and wrote critical articles. But most importantly, with his creativity, he paves realistic paths for the development of domestic musical art. His works reflected an even more grandiose in scale, irrepressible, in spite of all obstacles, craving for freedom of the enslaved Czech people.

In the midst of a fierce battle with the forces of public reaction, Smetana suffered a misfortune, worse than which there is no worse for a musician: he suddenly became deaf. He was then fifty years old. Experiencing severe physical suffering, Smetana lived another ten years, which he spent in intense creative work.

Performing activity ceased, but creative work continued with the same intensity. How not to recall Beethoven in this connection – after all, the history of music knows no other examples so striking in the manifestation of the greatness of the spirit of an artist, courageous in misfortune! ..

The highest achievements of Smetana are connected with the field of opera and program symphony.

As a sensitive artist-citizen, having started his reform activities in the 1860s, Smetana first of all turned to opera, because it was in this area that the most urgent, topical issues of the formation of national artistic culture were resolved. “The main and noblest task of our opera house is to develop domestic art,” he said. Many aspects of life are reflected in his eight opera creations, various genres of opera art are fixed. Each of them is marked by individually unique features, but all of them have one dominant feature – in Smetana’s operas, the images of ordinary people of the Czech Republic and its glorious heroes, whose thoughts and feelings are close to a wide range of listeners, came to life.

Smetana also turned to the field of program symphonism. It was the concreteness of the images of textless program music that allowed the composer to convey his patriotic ideas to the masses of listeners. The largest among them is the symphonic cycle “My Motherland”. This work played a huge role in the development of Czech instrumental music.

Smetana also left many other works – for unaccompanied choir, piano, string quartet, etc. Whatever genre of musical art he turned to, everything that the exacting hand of the master touched flourished as a nationally original artistic phenomenon, standing on the level of high achievements of the world musical culture of the XIX century.

It begs a comparison of the historical role of Smetana in the creation of Czech musical classics with what Glinka did for Russian music. No wonder Smetana is called the “Czech Glinka”.

* * *

Bedrich Smetana was born on March 2, 1824 in the ancient town of Litomysl, located in southeastern Bohemia. His father served as a brewer on the count’s estate. Over the years, the family grew, the father had to look for more favorable conditions for work, and he often moved from place to place. All these were also small towns, surrounded by villages and villages, which young Bedrich often visited; the life of the peasants, their songs and dances were well known to him from childhood. He retained his love for the common people of the Czech Republic for the rest of his life.

The father of the future composer was an outstanding person: he read a lot, was interested in politics, and was fond of the ideas of the awakeners. Music was often played in the house, he himself played the violin. It is not surprising that the boy also showed an early interest in music, and his father’s progressive ideas gave wonderful results in the mature years of Smetana’s activity.

From the age of four, Bedřich has been learning to play the violin, and so successfully that a year later he takes part in the performance of Haydn’s quartets. For six years he performs publicly as a pianist and at the same time tries to compose music. While studying at the gymnasium, in a friendly environment, he often improvises dances (the graceful and melodic Louisina Polka, 1840, has been preserved); plays the piano diligently. In 1843, Bedrich writes proud words in his diary: “With God’s help and mercy, I will become Liszt in technique, Mozart in composition.” The decision is ripe: he must devote himself entirely to music.

A seventeen-year-old boy moves to Prague, lives hand to mouth – his father is dissatisfied with his son, refuses to help him. But Bedrich found himself a worthy leader – the famous teacher Josef Proksh, to whom he entrusted his fate. Four years of studies (1844-1847) were very fruitful. The formation of Smetana as a musician was also facilitated by the fact that in Prague he managed to listen to Liszt (1840), Berlioz (1846), Clara Schumann (1847).

By 1848, the years of study were over. What is their outcome?

Even in his youth, Smetana was fond of the music of ballroom and folk dances – he wrote waltzes, quadrilles, gallops, polkas. He was, it would seem, in line with the traditions of fashionable salon authors. The influence of Chopin, with his ingenious ability to poetically translate dance images, also affected. In addition, the young Czech musician aspired.

He also wrote romantic plays – a kind of “landscapes of moods”, falling under the influence of Schumann, partly Mendelssohn. However, Smetana has a strong classic “sourdough”. He admires Mozart, and in his first major compositions (piano sonatas, orchestral overtures) relies on Beethoven. Still, Chopin is closest to him. And as a pianist, he often plays his works, being, according to Hans Bülow, one of the best “Chopinists” of his time. And later, in 1879, Smetana pointed out: “To Chopin, to his works, I owe the success that my concerts enjoyed, and from the moment I learned and understood his compositions, my creative tasks in the future were clear to me.”

So, at the age of twenty-four, Smetana had already completely mastered both composing and pianistic techniques. He only needed to find an application for his powers, and for this it was better to know himself.

By that time, Smetana had opened a music school, which gave him the opportunity to somehow exist. He was on the verge of marriage (took place in 1849) – you need to think about how to provide for your future family. In 1847, Smetana undertook a concert tour around the country, which, however, did not materially justify itself. True, in Prague itself he is known and appreciated as a pianist and teacher. But Smetana the composer is almost completely unknown. In desperation, he turns to Liszt for help in writing, sadly asking: “Who can an artist trust if not the same artist as he himself is? The rich – these aristocrats – look at the poor without pity: let him die of hunger! ..». Smetana attached his “Six characteristic pieces” for piano to the letter.

A noble propagandist of everything advanced in art, generous with help, Liszt immediately answered the young musician hitherto unknown to him: “I consider your plays to be the best, deeply felt and finely developed among all that I have managed to get acquainted with in recent times.” Liszt contributed to the fact that these plays were printed (they were published in 1851 and marked op. 1). From now on, his moral support accompanied all the creative undertakings of Smetana. “The sheet,” he said, “introduced me to the artistic world.” But many more years will pass until Smetana manages to achieve recognition in this world. The revolutionary events of 1848 served as the impetus.

The revolution gave wings to the patriotic Czech composer, gave him strength, helped him to realize those ideological and artistic tasks that were persistently put forward by modern reality. Witness and direct participant in the violent unrest that swept Prague, Smetana in a short time wrote a number of significant works: “Two Revolutionary Marches” for piano, “March of the Student Legion”, “March of the National Guard”, “Song of Freedom” for choir and piano, overture” D-dur (The overture was performed under the direction of F. Shkroup in April 1849. “This is my first orchestral composition,” Smetana pointed out in 1883; then he revised it.).

With these works, pathos is established in Smetana’s music, which will soon become typical for his interpretation of freedom-loving patriotic images. The marches and hymns of the French Revolution at the end of the XNUMXth century, as well as the heroism of Beethoven, had a noticeable influence on its formation. There is an effect, albeit timidly, of the influence of Czech hymn song, born of the Hussite movement. The national warehouse of sublime pathos, however, will clearly manifest itself only in the mature period of Smetana’s work.

His next major work was the Solemn Symphony in E major, written in 1853 and first performed two years later under the direction of the author. (This was his first performance as a conductor). But when transmitting larger-scale ideas, the composer has not yet been able to reveal the full originality of his creative individuality. The third movement turned out to be more original – a scherzo in the spirit of polka; it was later often performed as an independent orchestral piece. Smetana himself soon realized the inferiority of his symphony and no longer turned to this genre. His younger colleague, Dvořák, became the creator of the national Czech symphony.

These were the years of intensive creative searches. They taught Smetana a lot. All the more he was burdened by the narrow sphere of pedagogy. In addition, personal happiness was overshadowed: he had already become the father of four children, but three of them died in infancy. The composer captured his sorrowful thoughts caused by their death in the g-moll piano trio, whose music is characterized by rebellious impetuosity, drama and at the same time soft, nationally colored elegiacity.

Life in Prague got sick of Smetana. He could no longer remain in it when the darkness of reaction deepened even more in the Czech Republic. On the advice of friends, Smetana leaves for Sweden. Before leaving, he finally made the acquaintance of Liszt personally; then, in 1857 and 1859, he visited him in Weimar, in 1865 – in Budapest, and Liszt, in turn, when he came to Prague in the 60-70s, always visited Smetana. Thus, the friendship between the great Hungarian musician and the brilliant Czech composer grew stronger. They were brought together not only by artistic ideals: the peoples of Hungary and the Czech Republic had a common enemy – the hated Austrian monarchy of the Habsburgs.

For five years (1856-1861) Smetana was in a foreign land, living mainly in the seaside Swedish city of Gothenburg. Here he developed a vigorous activity: he organized a symphony orchestra, with which he performed as a conductor, successfully gave concerts as a pianist (in Sweden, Germany, Denmark, Holland), and had many students. And in a creative sense, this period was fruitful: if 1848 caused a decisive change in the worldview of Smetana, strengthening progressive features in it, then the years spent abroad contributed to the strengthening of his national ideals and, at the same time, to the growth of skill. It can be said that it was during these years, yearning for his homeland, that Smetana finally realized his vocation as a national Czech artist.

His compositional work developed in two directions.

On the one hand, the experiments started earlier on the creation of piano pieces, covered with the poetry of Czech dances, continued. So, back in 1849, the cycle “Wedding Scenes” was written, which many years later Smetana himself described as conceived in a “true Czech style.” The experiments were continued in another piano cycle – “Memories of the Czech Republic, written in the form of a polka” (1859). Here the national foundations of Smetana’s music were laid, but mainly in the lyrical and everyday interpretation.

On the other hand, three symphonic poems were important for his artistic evolution: Richard III (1858, based on the tragedy of Shakespeare), Wallenstein’s Camp (1859, based on the drama by Schiller), Jarl Hakon (1861, based on the tragedy of the Danish poet – the romance of Helenschläger). They improved the sublime pathos of Smetana’s work, associated with the embodiment of heroic and dramatic images.

First of all, the themes of these works are noteworthy: Smetana was fascinated by the idea of uXNUMXbuXNUMXbthe struggle against the usurpers of power, clearly expressed in the literary works that formed the basis of his poems (by the way, the plot and images of the tragedy of the Dane Elenschleger echo Shakespeare’s Macbeth), and juicy scenes from folk life, especially in Schiller’s “Wallenstein Camp”, which, according to the composer, could sound relevant during the years of cruel oppression of his homeland.

The musical concept of Smetana’s new compositions was also innovative: he turned to the genre of “symphonic poems”, developed shortly before by Liszt. These are the first steps of the Czech master in mastering the expressive possibilities that opened up to him in the field of program symphony. Moreover, Smetana was not a blind imitator of Liszt’s concepts – he forged his own methods of composition, his own logic of juxtaposition and development of musical images, which he later consolidated with remarkable perfection in the symphonic cycle “My Motherland”.

And in other respects, the “Gothenburg” poems were important approaches to solving new creative tasks that Smetana set for himself. The lofty pathos and drama of their music anticipates the style of the operas Dalibor and Libuše, while the cheerful scenes from Wallenstein’s Camp, splashing with merriment, colored with Czech flavor, seem to be a prototype of the overture to The Bartered Bride. Thus, the two most important aspects of Smetana’s work mentioned above, the folk-everyday and pathetic, came close, enriching each other.

From now on, he is already prepared for the accomplishment of new, even more responsible ideological and artistic tasks. But they can only be carried out at home. He also wanted to return to Prague because heavy memories are connected with Gothenburg: a new terrible misfortune fell upon Smetana – in 1859, his beloved wife fell mortally ill here and soon died …

In the spring of 1861, Smetana returned to Prague in order not to leave the capital of the Czech Republic until the end of his days.

He is thirty seven years old. He is full of creativity. The previous years tempered his will, enriched his life and artistic experience, and strengthened his self-confidence. He knows what he has to stand up for, what to achieve. Such an artist was called by fate itself to lead the musical life of Prague and, moreover, to renew the entire structure of the musical culture of the Czech Republic.

This was facilitated by the revival of the socio-political and cultural situation in the country. The days of “Bach’s reaction” are over. The voices of representatives of the progressive Czech artistic intelligentsia are growing stronger. In 1862, the so-called “Provisional Theatre” was opened, built with folk funds, where musical performances are staged. Soon the “Crafty Talk” – “Art Club” – began its activity, bringing together passionate patriots – writers, artists, musicians. At the same time, a choral association is being organized – “The Verb of Prague”, which inscribed on its banner the famous words: “Song to the heart, heart to the homeland.”

Smetana is the soul of all these organizations. He directs the musical section of the “Art Club” (writers are headed by Neruda, artists – by Manes), arranges concerts here – chamber and symphony, works with the “Verb” choir, and with his work contributes to the flourishing of the “Provisional Theater” (a few years later and as a conductor ).

In an effort to arouse a sense of Czech national pride in his music, Smetana often appeared in print. “Our people,” he wrote, “has long been famous as a musical people, and the task of the artist, inspired by love for the motherland, is to strengthen this glory.”

And in another article written about the subscription of symphony concerts organized by him (this was an innovation for the people of Prague!), Smetana stated: “Masterpieces of musical literature are included in the programs, but special attention is paid to Slavic composers. Why have not the works of Russian, Polish, South Slavic authors been performed so far? Even the names of our domestic composers were rarely met … “. Smetana’s words did not differ from his deeds: in 1865 he conducted Glinka’s orchestral works, in 1866 he staged Ivan Susanin at the Provisional Theatre, and in 1867 Ruslan and Lyudmila (for which he invited Balakirev to Prague), in 1878 – Moniuszko’s opera “Pebble”, etc.

At the same time, the 60s mark the period of the highest flowering of his work. Almost simultaneously, he had the idea of four operas, and as soon as he finished one, he proceeded to compose the next. In parallel, choirs were created for the “Verb” (The first choir to a Czech text was created in 1860 (“Czech Song”). Smetana’s major choral works are Rolnicka (1868), which sings of the labor of a peasant, and the widely developed, colorful Song by the Sea (1877). Among other compositions, the hymnal song “Dowry” (1880) and the joyful, jubilant “Our Song” (1883), sustained in the rhythm of polka, stand out.), piano pieces, major symphonic works were considered.

The Brandenburgers in the Czech Republic is the title of Smetana’s first opera, completed in 1863. It resurrects the events of the distant past, dating back to the XNUMXth century. Nevertheless, its content is acutely relevant. Brandenburgers are German feudal lords (from the Margraviate of Brandenburg), who plundered the Slavic lands, trampled on the rights and dignity of the Czechs. So it was in the past, but it remained so during the life of Smetana – after all, his best contemporaries fought against the Germanization of the Czech Republic! Exciting drama in the depiction of the personal destinies of the characters was combined in the opera with a display of the life of ordinary people – the Prague poor seized by the rebellious spirit, which was a bold innovation in musical theater. It is not surprising that this work was met with hostility by representatives of public reaction.

The opera was submitted to a competition announced by the directorate of the Provisional Theatre. Three years had to fight for her production on stage. Smetana finally received the award and was invited to the theater as the chief conductor. In 1866, the premiere of The Brandenburgers took place, which was a huge success – the author was repeatedly called after each act. Success accompanied the following performances (during the season alone, “The Brandenburgers” took place fourteen times!).

This premiere had not yet ended, when the production of a new composition by Smetana began to be prepared – the comic opera The Bartered Bride, which had glorified him everywhere. The first sketches for it were sketched out as early as 1862, the next year Smetana performed the overture in one of his concerts. The work was arguable, but the composer reworked individual numbers several times: as his friends said, he was so intensively “Czechized”, that is, he was more and more deeply imbued with the Czech folk spirit, that he could no longer be satisfied with what he had previously achieved. Smetana continued to improve his opera even after its production in the spring of 1866 (five months after the premiere of The Brandenburgers!): in the next four years, he gave two more editions of The Bartered Bride, expanding and deepening the content of his immortal work.

But the enemies of Smetana did not doze off. They were just waiting for an opportunity to openly attack him. Such an opportunity presented itself when in 1868 Smetana’s third opera, Dalibor, was staged (work on it began as early as 1865). The plot, as in Brandenburgers, is taken from the history of the Czech Republic: this time it is the end of the XNUMXth century. In an ancient legend about the noble knight Dalibor, Smetana emphasized the idea of a liberation struggle.

The innovative idea determined unusual means of expression. Opponents of Smetana branded him as an ardent Wagnerian who allegedly renounced national-Czech ideals. “I don’t have anything from Wagner,” Smetana objected bitterly. “Even Liszt will confirm this.” Nevertheless, the persecution intensified, the attacks became more and more violent. As a result, the opera only ran six times and was withdrawn from the repertoire.

(In 1870, “Dalibor” was given three times, in 1871 – two, in 1879 – three; only since 1886, after the death of Smetana, interest in this opera was revived. Gustav Mahler highly appreciated it, and when he was invited to lead conductor of the Vienna Opera, demanded that “Dalibor” be staged, the premiere of the opera took place in 1897. Two years later, she sounded under the direction of E. Napravnik at the St. Petersburg Mariinsky Theater.)

That was a strong blow for Smetana: he could not reconcile himself with such an unfair attitude towards his beloved offspring and even got angry with his friends when, lavishing praises on the Bartered Bride, they forgot about Dalibor.

But adamant and courageous in his quest, Smetana continues to work on the fourth opera – “Libuse” (the original sketches date back to 1861, the libretto was completed in 1866). This is an epic story based on a legendary story about a wise ruler of ancient Bohemia. Her deeds are sung by many Czech poets and musicians; their brightest dreams about the future of their homeland were associated with Libuse’s call for national unity and the moral stamina of the oppressed people. So, Erben put into her mouth a prophecy full of deep meaning:

I see the glow, I fight battles, A sharp blade will pierce your chest, You will know the troubles and the darkness of desolation, But do not lose heart, my Czech people!

By 1872 Smetana had completed his opera. But he refused to stage it. The fact is that a great national celebration was being prepared. Back in 1868, the laying of the foundation of the National Theater took place, which was supposed to replace the cramped premises of the Provisional Theatre. “The people – for themselves” – under such a proud motto, funds were collected for the construction of a new building. Smetana decided to time the premiere of “Libuše” to coincide with this national celebration. Only in 1881 the doors of the new theater opened. Smetana then could no longer hear his opera: he was deaf.

The worst of all the misfortunes that struck Smetana – deafness suddenly overtook him in 1874. To the limit, hard work, persecution of enemies, who with a frenzy took up arms against Smetana, gave rise to an acute disease of the auditory nerves and a tragic catastrophe. His life turned out to be warped, but his steadfast spirit was not broken. I had to give up performing activities, move away from social work, but the creative forces did not run out – the composer continued to create wonderful creations.

In the year of the disaster, Smetana completed his fifth opera, The Two Widows, which was a great success; it uses a comic plot from modern manor life.

At the same time, the monumental symphonic cycle “My Motherland” was being composed. The first two poems – “Vyshegrad” and “Vltava” – were completed in the most difficult months, when doctors recognized Smetana’s illness as incurable. In 1875 “Sharka” and “From Bohemian Fields and Woods” followed; in 1878-1879 – Tabor and Blanik. In 1882, the conductor Adolf Cech performed the entire cycle for the first time, and outside the Czech Republic – already in the 90s – it was promoted by Richard Strauss.

Work continued in the opera genre. Popularity almost equal to that of The Bartered Bride was gained by the lyrical-everyday opera The Kiss (1875-1876), in the center of which is the chaste image of a simple Vendulka girl; the opera The Secret (1877-1878), which also sang of fidelity in love, was warmly received; less successful because of the weak libretto was the last stage work of Smetana – “Devil’s Wall” (1882).

So, over the course of eight years, the deaf composer created four operas, a symphonic cycle of six poems, and a number of other works – piano, chamber, choral. What a will he must have had to be so productive! His strength, however, began to fail – sometimes he had nightmare visions; At times he seemed to be losing his mind. The craving for creativity overcame everything. Fantasy was inexhaustible, and an amazing inner ear helped to select the necessary means of expression. And another thing is surprising: despite the progressive nervous disease, Smetana continued to create music in a youthful way, fresh, truthful, optimistic. Having lost his hearing, he lost the possibility of direct communication with people, but he did not fence himself off from them, did not withdraw into himself, retaining the joyful acceptance of life so inherent in him, faith in it. The source of such inexhaustible optimism lies in the consciousness of inseparable proximity to the interests and destinies of the native people.

This inspired Smetana to create the magnificent Czech Dances piano cycle (1877-1879). The composer demanded from the publisher that each play – and there are fourteen in all – be provided with a title: polka, furiant, skochna, “Ulan”, “Oats”, “Bear”, etc. Any Czech from childhood is familiar with these names, said Sour cream; he published his cycle in order “to let everyone know what kind of dances we Czechs have.”

How typical this remark is for a composer who selflessly loved his people and always, in all his compositions, wrote about them, expressing feelings not narrowly personal, but general, close and understandable to everyone. Only in a few works Smetana allowed himself to talk about his personal drama. Then he resorted to the chamber-instrumental genre. Such is his piano trio, mentioned above, as well as two string quartets belonging to the last period of his work (1876 and 1883.)

The first of them is more significant – in the key of e-moll, which has a subtitle: “From my life”. In four parts of the cycle, important episodes of Smetana’s biography are recreated. First (the main part of the first part) sounds, as the composer explains, “the call of fate, calling for battle”; further – “an inexpressible craving for the unknown”; finally, “that fatal whistle of the highest tones, which in 1874 heralded my deafness …”. The second part – “in the spirit of the polka” – captures the joyful memories of youth, peasant dances, balls … In the third – love, personal happiness. The fourth part is the most dramatic. Smetana explains its content in this way: “Awareness of the great power that lies in our national music… achievements on this path… the joy of creativity, cruelly interrupted by a tragic catastrophe – hearing loss… glimmers of hope… memories of the beginning of my creative path… a poignant feeling of longing…”. Consequently, even in this most subjective work of Smetana, personal reflections are intertwined with thoughts about the fate of Russian art. These thoughts did not leave him until the last days of his life. And he was destined to go through both days of joy and days of great grief.

In 1880, the whole country solemnly celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of Smetana’s musical activity (we remind you that in 1830, as a six-year-old child, he publicly performed as a pianist). For the first time in Prague, his “Evening Songs” were performed – five romances for voice and piano. At the end of the festive concert, Smetana performed his polka and Chopin’s B major nocturne on the piano. Following Prague, the national hero was honored by the city of Litomysl, where he was born.

The following year, 1881, Czech patriots experienced great grief – the newly rebuilt building of the Prague National Theater burned down, where the premiere of Libuše had recently sounded. Fundraising is organized for its restoration. Smetana is invited to conduct his own compositions, he also performs in the provinces as a pianist. Tired, mortally ill, he sacrifices himself for a common cause: the proceeds from these concerts helped complete the construction of the National Theater, which reopened its first season with the Libuse opera in November 1883.

But Smetana’s days are already numbered. His health deteriorated sharply, his mind became clouded. On April 23, 1884, he died in a hospital for the mentally ill. Liszt wrote to friends: “I am shocked by the death of Smetana. He was a genius!

M. Druskin

- Operatic creativity of Smetana →

Compositions:

Operas (total 8) The Brandenburgers in Bohemia, libretto by Sabina (1863, premiered in 1866) The Bartered Bride, libretto by Sabina (1866) Dalibor, libretto by Wenzig (1867-1868) Libuse, libretto by Wenzig (1872, premiered in 1881) “Two Widows”, libretto by Züngl (1874) The Kiss, libretto by Krasnogorskaya (1876) “The Secret”, libretto by Krasnogorskaya (1878) “Devil’s Wall”, libretto by Krasnogorskaya (1882) Viola, libretto by Krasnogorskaya, based on Shakespeare’s comedy Twelfth Night (only Act I completed, 1884)

Symphonic works “Jubilant Overture” D-dur (1848) “Solemn Symphony” E-dur (1853) “Richard III”, symphonic poem (1858) “Camp Wallenstein”, symphonic poem (1859) “Jarl Gakon”, symphonic poem (1861) “Solemn March” to Shakespeare’s Celebrations (1864) “Solemn Overture” C-dur (1868) “My Motherland”, a cycle of 6 symphonic poems: “Vysehrad” (1874), “Vltava” (1874), “Sharka” (1875), “From Czech fields and forests” (1875), “Tabor” (1878), “Blanik” (1879) “Venkovanka”, polka for orchestra (1879) “Prague Carnival”, introduction and polonaise (1883)

Piano works Bagatelles and Impromptu (1844) 8 preludes (1845) Polka and Allegro (1846) Rhapsody in G minor (1847) Czech Melodies (1847) 6 Character Pieces (1848) March of the Student Legion (1848) March of the People’s Guard (1848) “Letters of Memories” (1851) 3 salon polkas (1855) 3 poetic polkas (1855) “Sketches” (1858) “Scene from Shakespeare’s Macbeth” (1859) “Memories of the Czech Republic in the form of a polka” (1859) “On the seashore”, study (1862) “Dreams” (1875) Czech dances in 2 notebooks (1877, 1879)

Chamber instrumental works Trio for piano, violin and cello g-moll (1855) First string quartet “From my life” e-moll (1876) “Native land” for violin and piano (1878) Second String Quartet (1883)

Vocal music “Czech Song” for mixed choir and orchestra (1860) “Renegade” for two-part choir (1860) “Three Horsemen” for male choir (1866) “Rolnicka” for male choir (1868) “Solemn Song” for male choir (1870) “Song by the Sea” for male choir (1877) 3 women’s choirs (1878) “Evening Songs” for voice and piano (1879) “Dowry” for male choir (1880) “Prayer” for male choir (1880) “Two Slogans” for male choir (1882) “Our Song” for male choir (1883)