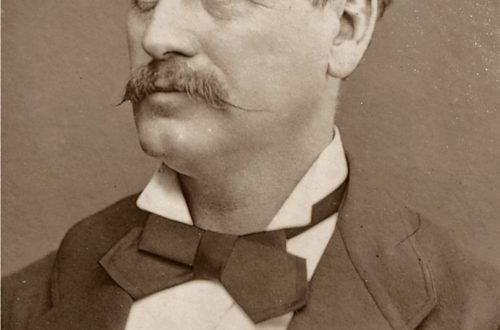

Alexander Borisovich Goldenweiser |

Alexander Goldenweiser

A prominent teacher, talented performer, composer, music editor, critic, writer, public figure – Alexander Borisovich Goldenweiser has successfully performed in all these qualities for many decades. He has always had a relentless pursuit of knowledge. This also applies to music itself, in which his erudition knew no bounds, this also applies to other areas of artistic creativity, this also applies to life itself in its various manifestations. The thirst for knowledge, the breadth of interests brought him to Yasnaya Polyana to see Leo Tolstoy, made him follow literary and theatrical novelties with the same enthusiasm, the ups and downs of matches for the world chess crown. “Alexander Borisovich,” wrote S. Feinberg, “is always keenly interested in everything new in life, literature and music. However, being a stranger to snobbery, no matter what area it may concern, he knows how to find, despite the rapid change in fashion trends and hobbies, enduring values - everything important and essential. And this was said in those days when Goldenweiser turned 85 years old!

Being one of the founders of the Soviet school of pianism. Goldenweiser personified the fruitful connection of times, passing on to new generations the testaments of his contemporaries and teachers. After all, his path in art began at the end of the last century. Over the years, he had to meet with many musicians, composers, writers, who had a significant impact on his creative development. However, based on the words of Goldenweiser himself, here one can single out key, decisive moments.

Childhood… “My first musical impressions,” Goldenweiser recalled, “I received from my mother. My mother did not have an outstanding musical talent; in her childhood she took piano lessons in Moscow for some time from the notorious Garras. She also sang a little. She had excellent musical taste. She played and sang Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Chopin, Mendelssohn. Father was often not at home in the evenings, and, being alone, mother played music for whole evenings. We children often listened to her, and when we went to bed, we got used to falling asleep to the sound of her music.

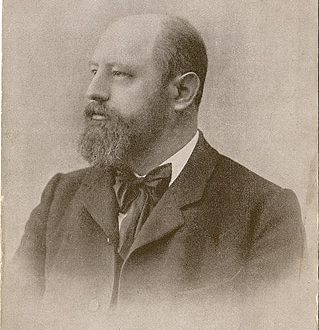

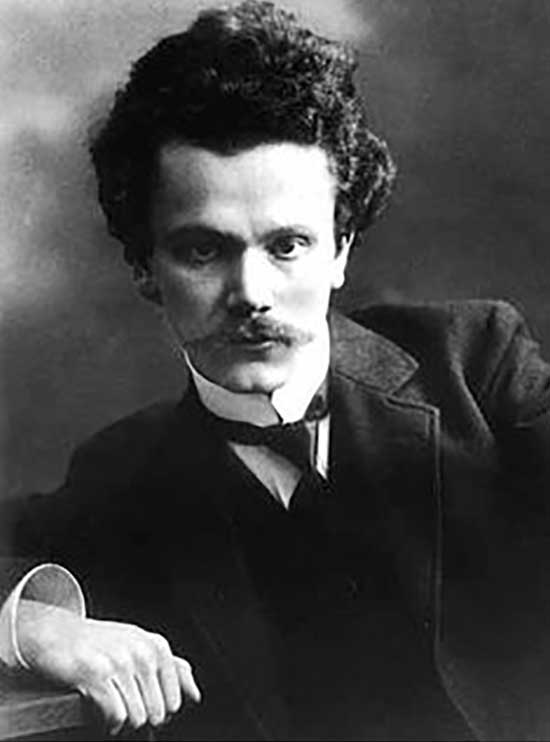

Later, he studied at the Moscow Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1895 as a pianist and in 1897 as a composer. A. I. Siloti and P. A. Pabst are his piano teachers. While still a student (1896) he gave his first solo concert in Moscow. The young musician mastered the art of composing under the guidance of M. M. Ippolitov-Ivanov, A. S. Arensky, S. I. Taneyev. Each of these illustrious teachers in one way or another enriched Goldenweiser’s artistic consciousness, but his studies with Taneyev and subsequently close personal contact with him had the greatest influence on the young man.

Another significant meeting: “In January 1896, a happy accident brought me to the house of Leo Tolstoy. Gradually I became a close person to him until his death. The influence of this closeness on my whole life was enormous. As a musician, L.N. first revealed to me the great task of bringing musical art closer to the broad masses of the people. (About his communication with the great writer, he would write a two-volume book “Near Tolstoy” much later.) Indeed, in his practical activities as a concert performer, Goldenweiser, even in the pre-revolutionary years, strove to be an educator musician, attracting democratic circles of listeners to music. He arranges concerts for a working audience, speaking at the house of the Russian Sobriety Society, in Yasnaya Polyana he holds original concerts-talks for peasants, and teaches at the Moscow People’s Conservatory.

This side of Goldenweiser’s activity was significantly developed in the first years after October, when for several years he headed the Musical Council, organized on the initiative of A. V. Lunacharsky: ” Department. This department began to organize lectures, concerts, and performances to serve the broad masses of the population. I went there and offered my services. Gradually the business grew. Subsequently, this organization came under the jurisdiction of the Moscow Council and was transferred to the Moscow Department of Public Education (MONO) and existed until 1917. We have formed departments: music (concert and educational), theatrical, lecture. I headed the concert department, in which a number of prominent musicians participated. We organized concert teams. N. Obukhova, V. Barsova, N. Raisky, B. Sibor, M, Blumenthal-Tamarina and others participated in my brigade … Our brigades served factories, factories, Red Army units, educational institutions, clubs. We traveled to the most remote areas of Moscow in winter on sledges, and in warm weather on dray shelves; sometimes performed in cold, unheated rooms. Nevertheless, this work gave all participants great artistic and moral satisfaction. The audience (especially where the work was carried out systematically) reacted vividly to the performed works; at the end of the concert, they asked questions, submitted numerous notes … “

The pianist’s pedagogical activity continued for more than half a century. While still a student, he began teaching at the Moscow Orphan’s Institute, then was a professor at the conservatory at the Moscow Philharmonic Society. However, in 1906, Goldenweiser linked his fate forever with the Moscow Conservatory. Here he trained more than 200 musicians. The names of many of his students are widely known – S. Feinberg, G. Ginzburg. R. Tamarkina, T. Nikolaeva, D. Bashkirov, L. Berman, D. Blagoy, L. Sosina… As S. Feinberg wrote, “Goldenweiser treated his students cordially and attentively. He presciently foresaw the fate of a young, not yet strong talent. How many times have we been convinced of his correctness, when in a young, seemingly imperceptible manifestation of creative initiative, he guessed a great talent that had not yet been discovered. Characteristically, Goldenweiser’s pupils went through the whole path of professional training – from childhood to graduate school. So, in particular, was the fate of G. Ginzburg.

If we touch on some methodological points in the practice of an outstanding teacher, then it is worth citing the words of D. Blagoy: “Goldenweiser himself did not consider himself a theorist of piano playing, modestly calling himself only a practicing teacher. The accuracy and conciseness of his remarks were explained, among other things, by the fact that he was able to draw the attention of students to the main, decisive moment in the work and at the same time to notice all the smallest details of the composition with exceptional accuracy, to appreciate the significance of each detail for understanding and embodying the whole. Distinguished by the utmost concreteness, all the remarks of Alexander Borisovich Goldenweiser led to serious and deep fundamental generalizations. Many other musicians also passed an excellent school in the class of Goldenweiser, among them the composers S. Evseev, D. Kabalevsky. V. Nechaev, V. Fere, organist L. Roizman.

And all this time, until the mid-50s, he continued to give concerts. There are solo evenings, performances with a symphony orchestra, and ensemble music with E. Izai, P. Casals, D. Oistrakh, S. Knushevitsky, D. Tsyganov, L. Kogan and other famous artists. Like any great musician. Goldenweiser had an original pianistic style. “We are not looking for physical power, sensual charm in this game,” A. Alschwang noted, “but we find subtle shades in it, an honest attitude towards the author being performed, good-quality work, a great genuine culture – and this is enough to make some of the master’s performances for a long time remembered by the audience. We do not forget some interpretations of Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann under the fingers of A. Goldenweiser.” To these names one can safely add Bach and D. Scarlatti, Chopin and Tchaikovsky, Scriabin and Rachmaninoff. “A great connoisseur of all classical Russian and Western musical literature,” wrote S. Feinberg, “he possessed an extremely wide repertoire… The enormous range of skill and artistry of Alexander Borisovich can be judged by his mastery of the most diverse styles of piano literature. He equally succeeded in the filigree Mozart style and the impetuously refined character of Scriabin’s creativity.

As you can see, when it comes to the Goldenweiser-performer, one of the first is the name of Mozart. His music, indeed, accompanied the pianist for almost his entire creative life. In one of the reviews of the 30s we read: “Goldenweiser’s Mozart speaks for himself, as if in the first person, speaks deeply, convincingly and fascinatingly, without false pathos and pop poses … Everything is simple, natural and truthful … Under the fingers of Goldenweiser comes to life all the versatility of Mozart – a man and a musician – his sunshine and sorrow, agitation and meditation, audacity and grace, courage and tenderness. Moreover, experts find Mozart’s beginning in Goldenweiser’s interpretations of the music of other composers.

Chopin’s works have always occupied a significant place in the pianist’s programs. “With great taste and a wonderful sense of style,” emphasizes A. Nikolaev, “Goldenweiser is able to bring out the rhythmic elegance of Chopin’s melodies, the polyphonic nature of his musical fabric. One of the features of Goldenweiser’s pianism is a very moderate pedalization, a certain graphic nature of the clear contours of the musical pattern, emphasizing the expressiveness of the melodic line. All this gives his performance a peculiar flavor, reminiscent of the links between Chopin’s style and Mozart’s pianism.

All the composers mentioned, and with them Haydn, Liszt, Glinka, Borodin, were also the object of attention of Goldenweiser, the music editor. Many classical works, including the sonatas of Mozart, Beethoven, the entire piano Schumann come to performers today in the exemplary edition of Goldenweiser.

Finally, mention should be made of the works of Goldenweiser the composer. He wrote three operas (“A Feast in the Time of Plague”, “Singers” and “Spring Waters”), orchestral, chamber-instrumental and piano pieces, and romances.

… So he lived a long life, full of work. And never knew peace. “He who has devoted himself to art,” the pianist liked to repeat, “must always strive forward. Not going forward means going backwards.” Alexander Borisovich Goldenweiser always followed the positive part of this thesis of his.

Lit .: Goldenweiser A. B. Articles, materials, memoirs / Comp. and ed. D. D. Blagoy. – M., 1969; On the art of music. Sat. articles, – M., 1975.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya.

Compositions:

operas – A feast during the plague (1942), Singers (1942-43), Spring waters (1946-47); cantata – Light of October (1948); for orchestra – overture (after Dante, 1895-97), 2 Russian suites (1946); chamber instrumental works – string quartet (1896; 2nd edition 1940), trio in memory of S. V. Rachmaninov (1953); for violin and piano — Poem (1962); for piano – 14 revolutionary songs (1932), Contrapuntal sketches (2 books, 1932), Polyphonic sonata (1954), Sonata fantasy (1959), etc., songs and romances.