Adriana and Leonora Baroni, Georgina, Maupin (Leonora Baroni) |

Leonora Baroni

The first prima donnas

When did prima donnas appear? After the appearance of the opera, of course, but this does not mean at all that at the same time as it. This title acquired the rights of citizenship at a time when the turbulent and changeable history of opera had been going through far from the first year, and the very form of this art form was born in a different environment than the brilliant performers who represented it. “Daphne” by Jacopo Peri, the first performance imbued with the spirit of ancient humanism and deserving the name of an opera, took place at the end of the 1597th century. Even the exact date is known – the year XNUMX. The performance was given in the house of the Florentine aristocrat Jacopo Corsi, the stage was an ordinary reception hall. There were no curtains or decorations. And yet, this date marks a revolutionary turning point in the history of music and theatre.

For almost twenty years the highly educated Florentines—including the music connoisseur Count Bardi, the poets Rinuccini and Cabriera, the composers Peri, Caccini, Marco di Gagliano, and the father of the great astronomer Vincenzo Galilei—had puzzled over how to adapt the high drama of the ancient Greeks to new style requirements. They were convinced that on the stage of classical Athens, the tragedies of Aeschylus and Sophocles were not only read and played, but also sung. How? It still remains a mystery. In the “Dialogue” that has come down to us, Galileo outlined his credo in the phrase “Oratio harmoniae domina absoluta” (Speech is the absolute mistress of harmony – lat.). It was an open challenge to the high culture of Renaissance polyphony, which reached its height in the work of Palestrina. Its essence was that the word was drowning in a complex polyphony, in a skillful interweaving of musical lines. What effect can the logos, which is the soul of every drama, have if not a single word of what is happening on the stage can be understood?

It is no wonder that numerous attempts were made to put music at the service of dramatic action. So that the audience would not get bored, a very serious dramatic work was interspersed with musical inserts included in the most inappropriate places, dances to the nines and dusts of discharged masks, comic interludes with a choir and canzones, even whole comedies-madrigals in which the choir asked questions and answered them. This was dictated by the love of theatricality, the mask, the grotesque and, last but not least, music. But the innate inclinations of the Italians, who adore music and theater like no other people, led in a roundabout way to the emergence of opera. True, the emergence of musical drama, this forerunner of opera, was possible only under one most important condition – beautiful music, so pleasing to the ear, had to be forcibly relegated to the role of accompaniment that would accompany a single voice isolated from polyphonic diversity, capable of pronouncing words, and such It can only be the voice of a person.

It is not difficult to imagine what amazement the audience experienced at the first performances of the opera: the voices of the performers were no longer drowned in the sounds of music, as was the case in their favorite madrigals, villanellas and frottolas. On the contrary, the performers clearly pronounced the text of their part, only relying on the support of the orchestra, so that the audience understood every word and could follow the development of the action on stage. The public, on the other hand, consisted of educated people, more precisely, of the chosen ones, who belonged to the upper strata of society – to aristocrats and patricians – from whom one could expect an understanding of innovation. Nevertheless, critical voices were not long in coming: they condemned the “boring recitation”, were indignant at the fact that it relegated music to the background, and lamented its lack with bitter tears. With their submission, in order to amuse the audience, madrigals and ritornellos were introduced into the performances, and the scene was decorated with a semblance of backstage to enliven. Yet the Florentine musical drama remained a spectacle for intellectuals and aristocrats.

So, under such conditions, could prima donnas (or whatever they were called at that time?) act as midwives at the birth of opera? It turns out that women have played an important role in this business from the very beginning. Even as composers. Giulio Caccini, who himself was a singer and composer of musical dramas, had four daughters, and they all played music, sang, played various instruments. The most capable of them, Francesca, nicknamed Cecchina, wrote the opera Ruggiero. This did not surprise contemporaries – all “virtuosos”, as the singers were then called, necessarily received a musical education. On the threshold of the XNUMXth century, Vittoria Arkilei was considered the queen among them. Aristocratic Florence hailed her as the herald of a new art form. Perhaps in it one should look for the prototype of the prima donna.

In the summer of 1610, a young Neapolitan woman appeared in the city that served as the cradle of opera. Adriana Basile was known in her homeland as a siren of vocals and enjoyed the favor of the Spanish court. She came to Florence at the invitation of her musical aristocracy. What exactly she sang, we do not know. But certainly not operas, hardly known to her then, although the fame of Ariadne by Claudio Monteverdi reached the south of Italy, and Basile performed the famous aria – Ariadne’s Complaint. Perhaps her repertoire included madrigals, the words to which were written by her brother, and the music, especially for Adriana, was composed by her patron and admirer, twenty-year-old Cardinal Ferdinand Gonzaga from a noble Italian family that ruled in Mantua. But something else is important for us: Adriana Basile eclipsed Vittoria Arcilei. With what? Voice, performance art? It is unlikely, because as far as we can imagine, Florentine music lovers had higher requirements. But Arkilei, though small and ugly, kept herself on stage with great self-esteem, as befits a true society lady. Adriana Basile is another matter: she captivated the audience not only with singing and playing the guitar, but also with beautiful blond hair over coal-black, purely Neapolitan eyes, a thoroughbred figure, feminine charm, which she used masterfully.

The meeting between Arkileia and the beautiful Adriana, which ended in the triumph of sensuality over spirituality (its radiance has reached us through the thickness of centuries), played a decisive role in those distant decades when the first prima donna was born. At the cradle of the Florentine opera, next to unbridled fantasy, there was reason and competence. They were not enough to make the opera and its main character – the “virtuoso” – viable; here two more creative forces were needed – the genius of musical creativity (Claudio Monteverdi became it) and eros. The Florentines freed the human voice from centuries of subjugation to music. From the very beginning, the high female voice personified pathos in its original meaning – that is, the suffering associated with the tragedy of love. How could Daphne, Eurydice and Ariadne, endlessly repeated at that time, touch their audience otherwise than by the love experiences inherent in all people without any distinctions, which were transmitted to the listeners only if the sung word fully corresponded to the entire appearance of the singer? Only after the irrational prevailed over discretion, and the suffering on the stage and the unpredictability of the action created fertile ground for all the paradoxes of the opera, did the hour strike for the appearance of the actress, whom we have the right to call the first prima donna.

She was originally a chic woman who performed in front of an equally chic audience. Only in an atmosphere of boundless luxury was the atmosphere inherent in her alone created – an atmosphere of admiration for erotica, sensuality and woman as such, and not for a skilled virtuoso like Arkileya. At first, there was no such atmosphere, despite the splendor of the Medici ducal court, neither in Florence with its aesthetic connoisseurs of opera, nor in papal Rome, where castrati had long supplanted women and expelled them from the stage, nor even under the southern sky of Naples, as if conducive to singing . It was created in Mantua, a small town in northern Italy, which served as the residence of powerful dukes, and later in the cheerful capital of the world – in Venice.

The beautiful Adriana Basile, mentioned above, came to Florence in transit: having married a Venetian named Muzio Baroni, she was heading with him to the court of the Duke of Mantua. The latter, Vincenzo Gonzaga, was a most curious personality who had no equal among the rulers of the early Baroque. Possessing insignificant possessions, squeezed on all sides by powerful city-states, constantly under the threat of attack from the warring Parma because of the inheritance, Gonzaga did not enjoy political influence, but compensated for it by playing an important role in the field of culture. Three campaigns against the Turks, in which he, a belated crusader, took part in his own person, until he fell ill with gout in the Hungarian camp, convinced him that investing his millions in poets, musicians and artists is much more profitable, and most importantly, more pleasant than in soldiers, military campaigns and fortresses.

The ambitious duke dreamed of being known as the main patron of the muses in Italy. A handsome blond, he was a cavalier to the marrow of his bones, he was an excellent swordsman and rode, which did not prevent him from playing the harpsichord and composing madrigals with talent, albeit amateurishly. It was only through his efforts that the pride of Italy, the poet Torquato Tasso, was released from the monastery in Ferrara, where he was kept among lunatics. Rubens was his court painter; Claudio Monteverdi lived for twenty-two years at the court of Vincenzo, here he wrote “Orpheus” and “Ariadne”.

Art and eros were integral parts of the life elixir that fueled this lover of the sweet life. Alas, in love he showed much worse taste than in art. It is known that once he retired incognito for the night with a girl to the closet of a tavern, at the door of which a hired killer lay in wait, in the end, by mistake, he plunged his dagger into another. If at the same time the frivolous song of the Duke of Mantua were also sung, why would you not like the same scene that was reproduced in the famous Verdi opera? Singers were especially fond of the duke. He bought one of them, Caterina Martinelli, in Rome and gave it as an apprenticeship to the court bandmaster Monteverdi – young girls were a particularly tasty morsel for the old gourmet. Katerina was irresistible in Orpheus, but at the age of fifteen she was carried away by a mysterious death.

Now Vincenzo has his eye on the “siren from the slopes of Posillipo,” Adriana Baroni of Naples. Rumors about her beauty and singing talent reached the north of Italy. Adriana, however, having also heard about the duke in Naples, don’t be a fool, decided to sell her beauty and art as dearly as possible.

Not everyone agrees that Baroni deserved the honorary title of the first prima donna, but what you can’t deny her is that in this case her behavior was not much different from the scandalous habits of the most famous prima donnas of the heyday of opera. Guided by her feminine instinct, she refused the duke’s brilliant proposals, put forward counter-proposals that were more profitable for her, turned to the help of intermediaries, of which the duke’s brother played the most important role. It was all the more piquant because the twenty-year-old nobleman, who held the post of cardinal in Rome, was head over heels in love with Adrian. Finally, the singer dictated her conditions, including a clause in which, in order to preserve her reputation as a married lady, it was stipulated that she would enter the service not of the illustrious Don Juan, but of his wife, who, however, had long been removed from her marital duties. According to the good Neapolitan tradition, Adriana brought her entire family with her as an attachment – her husband, mother, daughters, brother, sister – and even the servants. Departure from Naples looked like a court ceremony – crowds of people gathered around loaded carriages, rejoicing at the sight of their favorite singer, parting blessings of spiritual shepherds were heard every now and then.

In Mantua, the cortege was given an equally cordial welcome. Thanks to Adriana Baroni, concerts at the Duke’s court have acquired a new brilliance. Even the strict Monteverdi appreciated the talent of the virtuoso, who apparently was a talented improviser. True, the Florentines tried in every possible way to limit all those techniques with which conceited performers adorned their singing – they were considered incompatible with the high style of ancient musical drama. The great Caccini himself, of whom there are few singers, warned against excessive embellishment. What’s the point?! Sensuality and melody, which sought to splash out beyond the recitative, soon crept into the musical drama in the form of an aria, and concert performances opened up such an amazing virtuoso as Baroni with the widest opportunities to amaze the audience with trills, variations and other devices of this kind.

It must be assumed that, being at the Mantua court, Adriana was unlikely to be able to maintain her purity for a long time. Her husband, having received an enviable sinecure, was soon sent as a manager to a remote estate of the duke, and she herself, sharing the fate of her predecessors, gave birth to a child Vincenzo. Shortly thereafter, the duke died, and Monteverdi said goodbye to Mantua and moved to Venice. This ended the heyday of art in Mantua, which Adriana still found. Shortly before her arrival, Vincenzo built his own wooden theater for the production of Ariadne by Monteverdi, in which, with the help of ropes and mechanical devices, miraculous transformations were performed on the stage. The engagement of the duke’s daughter was coming, and the opera was to be the highlight of the celebration on this occasion. The lavish staging cost two million skudis. For comparison, let’s say that Monteverdi, the best composer of that time, received fifty scuds a month, and Adrian about two hundred. Even then, prima donnas were valued higher than the authors of the works they performed.

After the death of the duke, the luxurious court of the patron, along with the opera and the harem, fell into complete decline under the burden of millions of debts. In 1630, the landsknechts of the imperial general Aldringen – bandits and arsonists – finished off the city. Vincenzo’s collections, Monteverdi’s most precious manuscripts perished in the fire – only the heartbreaking scene of her weeping survived from Ariadne. The first stronghold of the opera turned into sad ruins. His sad experience demonstrated all the features and contradictions of this complex art form at an early stage of development: wastefulness and brilliance, on the one hand, and complete bankruptcy, on the other, and most importantly, an atmosphere filled with eroticism, without which neither the opera itself nor the prima donna could exist. .

Now Adriana Baroni appears in Venice. The Republic of San Marco became the musical successor of Mantua, but more democratic and decisive, and therefore had a greater influence on the fate of the opera. And not only because, until his imminent death, Monteverdi was the conductor of the cathedral and created significant musical works. Venice in itself opened up magnificent opportunities for the development of musical drama. It was still one of the most powerful states in Italy, with an incredibly wealthy capital that accompanied its political successes with orgies of unprecedented luxury. Love for a masquerade, for reincarnation, gave an extraordinary charm not only to the Venetian carnival.

Acting and playing music became the second nature of the cheerful people. Moreover, not only the rich participated in entertainments of this kind. Venice was a republic, albeit an aristocratic one, but the whole state lived on trade, which means that the lower strata of the population could not be excluded from art. The singer became a master in the theater, the public got access to it. From now on, the operas of Honor and Cavalli were listened to not by invited guests, but by those who paid for the entrance. Opera, which had been a ducal pastime in Mantua, turned into a profitable business.

In 1637, the patrician Throne family built the first public opera house in San Cassiano. It differed sharply from the classical palazzo with an amphitheater, such as, for example, the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza, which has survived to this day. The new building, of a completely different look, met the requirements of the opera and its public purpose. The stage was separated from the audience by a curtain, which for the time being hid from them the wonders of the scenery. The common public sat in the stalls on wooden benches, and the nobility sat in boxes that patrons often rented for the whole family. The lodge was a deep roomy room where secular life was in full swing. Here, not only the actors were applauded or booed, but secret love dates were often arranged. A real opera boom began in Venice. At the end of the XNUMXth century, at least eighteen theaters were built here. They flourished, then fell into decay, then passed into the hands of new owners and revived again – everything depended on the popularity of the performances and the attractiveness of the stars of the opera stage.

The art of singing quickly acquired features of high culture. It is generally accepted that the term “coloratura” was introduced into musical use by the Venetian composer Pietro Andrea Ciani. Virtuoso passages – trills, scales, etc. – decorating the main melody, they delighted the ear. The memo compiled in 1630 by the Roman composer Domenico Mazzocchi for his students testifies to how high the requirements were for opera singers. “First. In the morning. An hour of learning difficult opera passages, an hour of learning trills, etc., an hour of fluency exercises, an hour of recitation, an hour of vocalizations in front of a mirror in order to achieve a pose consistent with the musical style. Second. After lunch. Half an hour theory, half an hour counterpoint, half an hour literature. The rest of the day was devoted to composing canzonettes, motets or psalms.

In all likelihood, the universality and thoroughness of such education left nothing to be desired. It was caused by severe necessity, for young singers were forced to compete with castrati, castrated in childhood. By decree of the pope, the Roman women were forbidden to perform on stage, and their place was taken by men deprived of manhood. By singing, the men made up for the shortcomings for the opera stage of a blurry fat figure. The male artificial soprano (or alto) had a greater range than the natural female voice; there was no feminine brilliance or warmth in him, but there was a strength due to a more powerful chest. You will say – unnatural, tasteless, immoral … But at first the opera seemed unnatural, highly artificial and immoral. No objections helped: until the end of the 1601th century, marked by Rousseau’s call to return to nature, the half-man dominated the operatic scene in Europe. The church turned a blind eye to the fact that church choirs were replenished from the same source, although this was considered reprehensible. In XNUMX, the first castrato-sopranist appeared in the papal chapel, by the way, a pastor.

In later times, castrati, like the true kings of the opera, were caressed and showered with gold. One of the most famous – Caffarelli, who lived under Louis XV, was able to buy an entire duchy with his fees, and the no less famous Farinelli received fifty thousand francs a year from King Philip V of Spain just for entertaining the bored monarch daily with four opera arias.

And yet, no matter how the castrati were deified, the prima donna did not remain in the shadows. She had a power at her disposal, which she could use with the help of the legal means of the opera – the power of a woman. Her voice sounded in a refined stylized form that touches every person – love, hatred, jealousy, longing, suffering. Surrounded by legends, the figure of the singer in luxurious robes was the focus of desire for a society whose moral code was dictated by men. Let the nobility hardly tolerated the presence of singers of simple origin – the forbidden fruit, as you know, is always sweet. Even though the exits from the stage were locked and guarded to make it difficult to enter the dark boxes of the gentlemen, love conquered all obstacles. After all, it was so tempting to have an object of universal admiration! For centuries, opera has served as a source of love dreams thanks to prima donnas who compare favorably with modern Hollywood stars in that they could do much more.

In the turbulent years of the opera’s formation, traces of Adriana Baroni are lost. After leaving Mantua, she appears now in Milan, then in Venice. He sings the main roles in the operas of Francesco Cavalli, famous in those days. The composer was incredibly prolific, hence Adriana appears on stage quite often. Poets glorify the beautiful Baroni in sonnets, her sisters also make a career on the crest of the singer’s fame. The aging Adriana continues to delight admirers of her talent. Here is how the violist of Cardinal Richelieu, Pater Mogard, describes the concert idyll of the Baroni family: “Mother (Adriana) played the lyre, one daughter played the harp, and the second (Leonora) played the theorbo. The concerto for three voices and three instruments delighted me so much that it seemed to me that I was no longer a mere mortal, but was in the company of angels.

Finally leaving the stage, the beautiful Adriana wrote a book that can rightly be called a monument to her glory. And, which was then a great rarity, it was printed in Venice under the name “The Theater of Glory Signora Adriana Basile.” In addition to memoirs, it contained poems that poets and gentlemen laid at the feet of the theatrical diva.

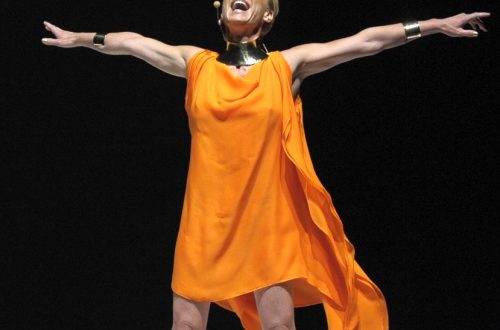

The glory of Adriana was reborn in her own flesh and blood – in her daughter Leonora. The latter even surpassed her mother, although Adriana still remains the first in order in the field of opera. Leonora Baroni captivated the Venetians, Florentines and Romans, in the eternal city she met the great Englishman Milton, who sang of her in one of his epigrams. Her admirers included the French ambassador to Rome, Giulio Mazzarino. Having become the all-powerful arbiter of the fate of France as Cardinal Mazarin, he invited Leonora with a troupe of Italian singers to Paris so that the French could enjoy the magnificent bel canto. In the middle of the XNUMXth century (composer Jean-Baptiste Lully and Moliere were then the masters of minds), the French court heard for the first time an Italian opera with the participation of the great “virtuoso” and castrato. So the glory of the prima donna crossed the borders of states and became the subject of national export. The same Father Mogar, praising the art of Leonora Baroni in Rome, especially admired her ability to thin out the sound to make a subtle distinction between the categories of chromatic and enharmony, which was a sign of Leonora’s exceptionally deep musical education. No wonder she, among other things, played the viola and the theorbo.

Following the example of her mother, she followed the path of success, but the opera developed, Leonora’s fame outgrew her mother’s, went beyond Venice and spread throughout Italy. She was also surrounded by adoration, poems are dedicated to her in Latin, Greek, Italian, French and Spanish, published in the collection Poets for the Glory of Signora Leonora Baroni.

She was known, along with Margherita Bertolazzi, as the greatest virtuoso of the first heyday of Italian opera. It would seem that envy and slander should have overshadowed her life. Nothing happened. The quarrelsomeness, eccentricity and inconstancy that later became typical for prima donnas, judging by the information that has come down to us, were not inherent in the first queens of vocals. It’s hard to say why. Either in Venice, Florence and Rome at the time of the early Baroque, despite the thirst for pleasure, too strict morals still prevailed, or there were few virtuosos, and those that were did not realize how great their power was. Only after the opera changed its appearance for the third time under the sultry sun of Naples, and the aria da capo, and after it the super-sophisticated voice fully established itself in the former dramma per musica, did the first adventurers, harlots and criminals appear among the actress-singers.

A brilliant career, for example, was made by Julia de Caro, the daughter of a cook and a wandering singer, who became a street girl. She managed to lead the opera house. After apparently killing her first husband and marrying a baby boy, she was booed and outlawed. She had to hide, certainly not with an empty wallet, and remain in obscurity for the rest of her days.

The Neapolitan spirit of intrigue, but already at the political and state levels, permeates the entire biography of Georgina, one of the most revered among the first prima donnas of the early Baroque. While in Rome, she earned the pope’s disfavor and was threatened with arrest. She fled to Sweden, under the auspices of the eccentric daughter of Gustavus Adolf, Queen Christina. Even then, all roads were open to adored prima donnas in Europe! Christina had such a weakness for the opera that it would be unforgivable to keep silent about her. Having renounced the throne, she converted to Catholicism, moved to Rome, and only through her efforts were women allowed to perform at the first public opera house in Tordinon. The papal ban did not resist the charms of the prima donnas, and how could it be otherwise if one cardinal himself helped the actresses, dressed in men’s clothes, sneak onto the stage, and the other – Rospigliosi, later Pope Clement IX, wrote poems to Leonora Baroni and composed plays.

After the death of Queen Christina, Georgina reappears among high-ranking political figures. She becomes the mistress of the Neapolitan Viceroy Medinaceli, who, sparing no expense, patronized the opera. But he was soon expelled, he had to flee to Spain with Georgina. Then he rose again, this time to the chair of the minister, but as a result of intrigue and conspiracy, he was thrown into prison, where he died. But when luck turned its back on Medinaceli, Georgina showed a character trait that has since been considered typical of prima donnas: loyalty! Previously, she shared the brilliance of wealth and nobility with her lover, but now she shared poverty with him, she herself went to jail, but after some time she was released, returned to Italy and lived comfortably in Rome until the end of her days.

The most stormy fate awaited the prima donna on the soil of France, in front of the luxurious backstage of the court theater in the secular capital of the world – Paris. Half a century later than Italy, he felt the charm of opera, but then the cult of the prima donna reached unprecedented heights there. The pioneers of the French theater were two cardinals and statesmen: Richelieu, who patronized the national tragedy and personally Corneille, and Mazarin, who brought the Italian opera to France, and helped the French to get on its feet. Ballet has long enjoyed the favor of the court, but the lyrical tragedy – opera – received full recognition only under Louis XIV. In his reign, the Italian Frenchman, Jean-Baptiste Lully, a former cook, dancer and violinist, became an influential court composer who wrote pathetic musical tragedies. Since 1669, lyrical tragedies with the obligatory admixture of dance were shown at the public opera house, called the Royal Academy of Music.

The laurels of the first great prima donna of France belong to Martha le Rochois. She had a worthy predecessor – Hilaire le Puy, but under her the opera had not yet taken shape in its final form. Le Puy had a great honor – she participated in a play in which the king himself danced the Egyptian. Martha le Rochois was by no means beautiful. Contemporaries depict her as a frail woman, with incredibly skinny hands, which she was forced to cover with long gloves. But she perfectly mastered the grandiloquent style of behavior on stage, without which the ancient tragedies of Lully could not exist. Martha le Rochois was especially glorified by her Armida, who shocked the audience with her soulful singing and regal posture. The actress has become, one might say, national pride. Only at the age of 48 did she leave the stage, receiving a position as a vocal teacher and a lifetime pension of a thousand francs. Le Rochois lived a quiet, respectable life, reminiscent of contemporary theater stars, and died in 1728 at the age of seventy-eight. It is even hard to believe that her rivals were two such notorious brawlers as Dematin and Maupin. This suggests that it is impossible to approach all prima donnas with the same standards. It is known about Dematin that she threw a bottle of lapel potion in the face of a pretty young woman, who was considered more beautiful, and the director of the opera, who bypassed her in the distribution of roles, almost killed her with the hands of a hired killer. Jealous of the success of Roshua, Moreau and someone else, she was about to send them all to the next world, but “the poison was not prepared in time, and the unfortunate escaped death.” But to the Archbishop of Paris, who cheated on her with another lady, she nevertheless “managed to slip a fast-acting poison, so that he soon died in his castle of pleasure.”

But all this seems like child’s play compared to the antics of the frantic Maupin. They sometimes resemble the crazy world of Dumas’ Three Musketeers, with the difference, however, that if Maupin’s life story were embodied in a novel, it would be perceived as a fruit of the author’s rich imagination.

Her origin is unknown, it is only precisely established that she was born in 1673 in Paris and just a girl jumped out to marry an official. When Monsieur Maupin was transferred to serve in the provinces, he had the imprudence to leave his young wife in Paris. Being a lover of purely male occupations, she began to take fencing lessons and immediately fell in love with her young teacher. The lovers fled to Marseilles, and Maupin changed into a man’s dress, and not only for the sake of being unrecognizable: most likely, she spoke of a desire for same-sex love, still unconscious. And when a young girl fell in love with this false young man, Maupin at first made fun of her, but soon unnatural sex became her passion. Meanwhile, having squandered all the money they had, a couple of fugitives discovered that singing can earn a living and even get an engagement in a local opera group. Here Maupin, acting in the guise of Monsieur d’Aubigny, falls in love with a girl from the high society of Marseille. Her parents, of course, do not want to hear about the marriage of their daughter with a suspicious comedian and for the sake of safety they hide her in a monastery.

The reports of Maupin’s biographers about her future fate can, at one’s own discretion, be taken on faith or attributed to the sophisticated imagination of the authors. It is also possible that they are the fruit of her self-promotion – Maupin’s unmistakable instinct suggested that a bad reputation can sometimes be easily turned into cash. So, we learn that Maupin, this time in the form of a woman, enters the same monastery in order to be close to her beloved, and waits for an opportune moment to escape. This is what it looks like when an old nun dies. Maupin allegedly digs up her corpse and puts it on the bed of his beloved. Further, the situation becomes even more criminal: Maupin sets a fire, panic arises, and in the ensuing turmoil, she runs with the girl. The crime, however, is discovered, the girl is returned to her parents, and Maupin is arrested, put on trial and sentenced to death. But she somehow manages to escape, after which her traces are lost for a while – apparently, she leads a vagabond life and prefers not to stay in one place.

In Paris, she manages to show herself to Lully. Her talent is recognized, the maestro trains her, and in a short time she makes her debut at the Royal Academy under her real name. Performing in Lully’s opera Cadmus et Hermione, she conquers Paris, poets sing of the rising star. Her extraordinary beauty, temperament and natural talent captivate the audience. She was especially successful in male roles, which is not surprising given her inclinations. But generous Paris treats them favorably. This seems especially remarkable if we remember that, unlike other strongholds of operatic art in France, castrati were never allowed to enter the stage. They try not to get involved with the young prima donna. Having once quarreled with her colleague, a singer named Dumesnil, she demanded an apology from him, and not having received them, she attacked a young healthy man with her fists so quickly that he did not even have time to blink an eye. She not only beat him, but also took away the snuffbox and watch, which later served as important material evidence. When the next day the poor fellow began to explain to his comrades that his numerous bruises were the result of an attack by bandits, Maupin triumphantly announced that this was the work of her hands and, for greater persuasiveness, threw things at the feet of the victim.

But that’s not all. Once she appeared at the party, again in a man’s dress. A quarrel broke out between her and one of the guests, Maupin challenged him to a duel. They fought with pistols. Mopan turned out to be a more dexterous shooter and crushed the opponent’s arm. In addition to being injured, he also experienced moral damage: the case received publicity, nailing the poor fellow forever to the pillory: he was defeated by a woman! An even more incredible incident took place at a masquerade ball – there Maupin in the palace garden fought with swords with three nobles at once. According to some reports, she killed one of them, according to others – all three. It was not possible to hush up the scandal, the judicial authorities became interested in them, and Maupin had to look for new stages. To remain in France was, apparently, dangerous, and then we meet with her already in Brussels, where she is naturally accepted as an opera star. She falls in love with Elector Maximilian of Bavaria and becomes his mistress, which does not prevent her from suffering so much from unrequited feelings for the girl that she even tries to lay hands on herself. But the elector has a new hobby, and he – a noble man – sends Maupin forty thousand francs of compensation. Enraged Maupin throws a purse with money at the messenger’s head and showers the elector with the last words. A scandal arises again, she can no longer stay in Brussels. She tries her luck in Spain, but slides down to the bottom of society and becomes a maid to a capricious countess. She is missing for a long time – she takes off and goes all-in – trying to re-conquer the Parisian stage, on which she won so many victories. And indeed – the brilliant prima donna is forgiven for all her sins, she gets a new chance. But, alas, she is no longer the same. The dissolute way of life was not in vain for her. At only thirty-two or thirty-four, she is forced to leave the stage. Her further life, calm and well-fed, is of no interest. The volcano is out!

There is extremely little reliable information about the tortuous life path of this woman, and this is far from an exception. In the same way, even the names of the founders of a new kind of art, who labored in the opera field in the early days of the appearance of prima donnas, are drowning in the twilight or in complete darkness of fate. But it is not so important whether Maupin’s biography is historical truth or a legend. The main thing is that it speaks of the readiness of society to attribute all these qualities to every significant prima donna and consider her sexuality, adventurism, sexual perversions, etc. as an integral part of the intricate operatic reality as its stage charm.

K. Khonolka (translation — R. Solodovnyk, A. Katsura)