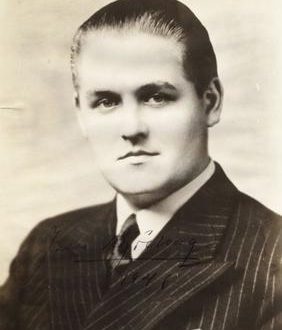

Luigi Marchesi |

Luigi Marchesi

Marchesi is one of the last famous castrato singers of the late XNUMXth and early XNUMXth centuries. Stendhal in his book “Rome, Naples, Florence” called him “Bernini in music”. “Marchesi had a voice of soft timbre, virtuoso coloratura technique,” notes S.M. Grishchenko. “His singing was distinguished by nobility, subtle musicality.”

Luigi Lodovico Marchesi (Marchesini) was born on August 8, 1754 in Milan, the son of a trumpeter. He first learned to play the hunting horn. Later, having moved to Modena, he studied singing with the teacher Caironi and the singer O. Albuzzi. In 1765, Luigi became the so-called alievo musico soprano (junior soprano castrato) at Milan Cathedral.

The young singer made his debut in 1774 in the capital of Italy in Pergolesi’s opera Maid-Mistress with a female part. Apparently, very successfully, since the following year in Florence he again performed the female role in Bianchi’s opera Castor and Pollux. Marchesi also sang female roles in operas by P. Anfossi, L. Alessandri, P.-A. Guglielmi. A few years after one of the performances, it was in Florence that Kelly wrote: “I sang Bianchi’s Sembianza amabile del mio bel sole with the most refined taste; in one chromatic passage he soared an octave of chromatic notes, and the last note was so exquisitely powerful and strong that it was called the Marchesi bomb.

Kelly has another review of the Italian singer’s performance after watching Myslivecek’s Olympiad in Naples: “His expressiveness, feeling and performance in the beautiful aria ‘se Cerca, se Dice’ were beyond praise.”

Marchesi gained great fame by performing in Milan’s La Scala theater in 1779, where the following year his triumph in Myslivechek’s Armida was awarded the Academy’s silver medal.

In 1782, in Turin, Marchesi achieved tremendous success in Bianchi’s Triumph of the World. He becomes the court musician of the King of Sardinia. The singer is entitled to a good annual salary – 1500 Piedmontese lire. In addition, he is allowed to tour abroad for nine months of the year. In 1784, in the same Turin, “musico” participated in the first performance of the opera “Artaxerxes” by Cimarosa.

“In 1785, he even reached St. Petersburg,” writes E. Harriot in his book about castrato singers, “but, frightened by the local climate, he hastily left for Vienna, where he spent the next three years; in 1788 he performed very successfully in London. This singer was famous for his victories over women’s hearts and caused a scandal when Maria Cosway, the miniaturist’s wife, left her husband and children for him and began to follow him all over Europe. She returned home only in 1795.

Marchesi’s arrival in London caused a sensation. On the first evening, his performance could not begin because of the noise and confusion that reigned in the hall. The famous English music lover Lord Mount Egdcombe writes: “At this time, Marchesi was a very handsome young man, with a fine figure and graceful movements. His playing was spiritual and expressive, his vocal abilities were completely unlimited, his voice struck with its range, although it was a little deaf. He played his part well, but gave the impression that he admired himself too much; besides, he was better at bravura episodes than cantabile. In recitatives, energetic and passionate scenes, he had no equal, and if he were less committed to melismas, which are not always appropriate, and if he had a purer and simpler taste, his performance would be impeccable: in any case, he is always lively, brilliant and bright. . For his debut, he chose Sarti’s charming opera Julius Sabin, in which all the arias of the protagonist (and there are many of them, and they are very diverse) are distinguished by the finest expressiveness. All these arias are familiar to me, I heard them performed by Pacchierotti at an evening in a private house, and now I missed his gentle expression, especially in the last pathetic scene. It seemed to me that Marchesi’s overly flamboyant style damaged their simplicity. Comparing these singers, I could not admire Marchesi as I had admired him before, in Mantua or in other operas here in London. He was received with a deafening ovation.”

In the capital of England, the only kind of friendly competition of two famous castrato singers, Marchesi and Pacchierotti, took place at a private concert in the house of Lord Buckingham.

Toward the end of the singer’s tour, one of the English newspapers wrote: “Last evening, Their Majesties and Princesses honored the opera house with their presence. Marchesi was the subject of their attention, and the hero, encouraged by the presence of the Court, outdid himself. Lately he has largely recovered from his predilection for excessive ornamentation. He still demonstrates on the stage the wonders of his commitment to science, but not to the detriment of art, without unnecessary decorations. However, the harmony of sound means as much to the ear as the harmony of the spectacle to the eye; where it is, it can be brought to perfection, but if it is not, all efforts will be in vain. Alas, it seems to us that Marchesi does not have such harmony.”

Until the end of the century Marchesi remains one of the most popular artists in Italy. And the listeners were ready to forgive their virtuosos a lot. Is it because at that time the singers could put forward almost any of the most ridiculous demands. Marchesi “succeeded” in this field as well. Here is what E. Harriot writes: “Marchesi insisted that he should appear on stage, descending the hill on horseback, always in a helmet with a multi-colored plume no less than a yard high. Fanfares or trumpets were to announce his departure, and the part was to begin with one of his favorite arias – most often “Mia speranza, io pur vorrei”, which Sarti wrote especially for him – regardless of the role played and the proposed situation. Many singers had such nominal arias; they were called “arie di baule” – “suitcase arias” – because the performers moved with them from theater to theater.

Vernon Lee writes: “The more frivolous part of the society was engaged in chatting and dancing and adored … the singer Marchesi, whom Alfieri called on to put on a helmet and go to battle with the French, calling him the only Italian who dared to resist the “Corsican Gaul” – the conqueror, at least and song.”

There is an allusion here to 1796, when Marchesi refused to speak to Napoleon in Milan. That, however, did not prevent Marchesi later, in 1800, after the Battle of Marengo, to become in the forefront of those who welcomed the usurper.

In the late 80s, Marchesi made his debut at the San Benedetto Theater in Venice in Tarki’s opera The Apotheosis of Hercules. Here, in Venice, there is a permanent rivalry between Marchesi and the Portuguese prima donna Donna Luisa Todi, who sang at the San Samuele Theatre. Details of this rivalry can be found in a 1790 letter from the Venetian Zagurri to his friend Casanova: “They say little about the new theater (La Fenice. – Approx. Auth.), The main topic for citizens of all classes is the relationship between Todi and Marchesi; talk about this will not subside until the end of the world, because such stories only strengthen the union of idleness and insignificance.

And here is another letter from him, written a year later: “They printed a caricature in the English style, in which Todi is depicted in triumph, and Marchesi is depicted in the dust. Any lines written in Marchesi’s defense are distorted or removed by the decision of Bestemmia (a special court to combat libel. – Approx. Aut.). Any nonsense that glorifies Todi is welcome, since she is under the auspices of Damone and Kaz.

It got to the point that rumors began to spread about the death of the singer. This was done to offend and frighten Marchesi. So one English newspaper of 1791 wrote: “Yesterday, information was received about the death of a great performer in Milan. It is said that he fell victim to the jealousy of an Italian aristocrat, whose wife was suspected of being too fond of the unfortunate nightingale … It is reported that the direct cause of the misfortune was poison, introduced with purely Italian skill and dexterity.

Despite the intrigues of enemies, Marchesi performed in the city of canals for several more years. In September 1794, Zagurri wrote: “Marchesi should sing this season at the Fenice, but the theater is so badly built that this season will not last long. Marchesi will cost them 3200 sequins.”

In 1798, in this theater, “Muziko” sang in Zingarelli’s opera with the strange name “Caroline and Mexico”, and he performed the part of the mysterious Mexico.

In 1801, the Teatro Nuovo opened in Trieste, where Marchesi sang in Mayr’s Ginevra Scottish. The singer ended his operatic career in the 1805/06 season, and until that time continued successful performances in Milan. Marchesi’s last public performance took place in 1820 in Naples.

Marchesi’s best male soprano roles include Armida (Mysliveček’s Armida), Ezio (Alessandri’s Ezio), Giulio, Rinaldo (Sarti’s Giulio Sabino, Armida and Rinaldo), Achilles (Achilles on Skyros) yes Capua).

The singer died on December 14, 1829 in Inzago, near Milan.