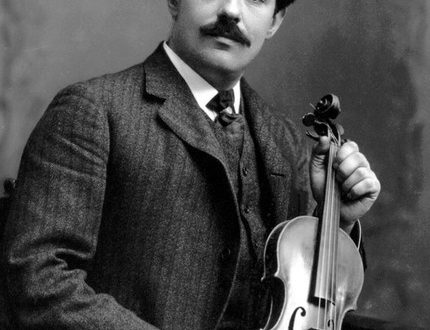

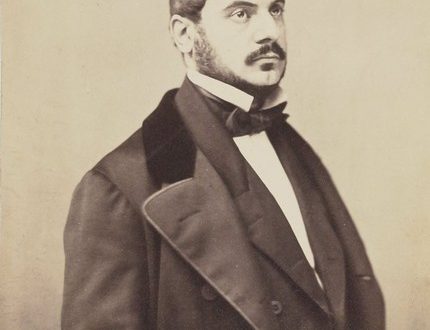

Ludwig (Louis) Spohr |

louis spohr

Spohr entered the history of music as an outstanding violinist and major composer who wrote operas, symphonies, concertos, chamber and instrumental works. Especially popular were his violin concertos, which served in the development of the genre as a link between classical and romantic art. In the operatic genre, Spohr, along with Weber, Marschner and Lortzing, developed national German traditions.

The direction of Spohr’s work was romantic, sentimentalist. True, his first violin concertos were still close in style to the classical concertos of Viotti and Rode, but subsequent ones, starting with the Sixth, became more and more romanticized. The same thing happened in operas. In the best of them – “Faust” (on the plot of a folk legend) and “Jessonde” – in some ways he even anticipated “Lohengrin” by R. Wagner and the romantic poems of F. Liszt.

But precisely “something”. Spohr’s talent as a composer was neither strong, nor original, nor even solid. In music, his sentimentalized romance clashes with pedantic, purely German thoughtfulness, preserving the normativity and intellectualism of the classical style. Schiller’s “struggle of feelings” was alien to Spohr. Stendhal wrote that his romanticism expresses “not the passionate soul of Werther, but the pure soul of a German burgher”.

R. Wagner echoes Stendhal. Calling Weber and Spohr outstanding German opera composers, Wagner denies them the ability to handle the human voice and considers their talent not too deep to conquer the realm of drama. In his opinion, the nature of Weber’s talent is purely lyrical, while Spohr’s is elegiac. But their main drawback is learning: “Oh, this accursed learning of ours is the source of all German evils!” It was scholarship, pedantry and burgher respectability that once made M. Glinka ironically call Spohr “a stagecoach of strong German work.”

However, no matter how strong the features of the burghers were in Spohr, it would be wrong to consider him a kind of pillar of philistinism and philistinism in music. In the personality of Spohr and his works there was something that opposed philistinism. Spur cannot be denied nobility, spiritual purity and sublimity, especially attractive at a time of unbridled passion for virtuosity. Spohr did not profane the art he loved, passionately rebelling against what seemed to him petty and vulgar, serving base tastes. Contemporaries appreciated his position. Weber writes sympathetic articles about Spohr’s operas; Spohr’s symphony “The Blessing of Sounds” was called remarkable by V. F. Odoevsky; Liszt conducting Spohr’s Faust in Weimar on 24 October 1852. “According to G. Moser, the songs of the young Schumann reveal the influence of Spohr.” Spohr had a long friendly relationship with Schumann.

Spohr was born on April 5, 1784. His father was a doctor and passionately loved music; he played the flute well, his mother played the harpsichord.

The son’s musical abilities showed up early. “Gifted with a clear soprano voice,” writes Spohr in his autobiography, “I first began to sing and for four or five years I was allowed to sing a duet with my mother at our family parties. By this time, my father, yielding to my ardent desire, bought me a violin at the fair, on which I began to play incessantly.

Noticing the boy’s giftedness, his parents sent him to study with a French emigrant, an amateur violinist Dufour, but soon transferred to a professional teacher Mokur, concertmaster of the Duke of Brunswick’s orchestra.

The young violinist’s playing was so bright that the parents and the teacher decided to try their luck and find an opportunity for him to perform in Hamburg. However, the concert in Hamburg did not take place, as the 13-year-old violinist, without the support and patronage of the “powerful ones”, failed to attract due attention to himself. Returning to Braunschweig, he joined the duke’s orchestra, and when he was 15 years old, he already held the position of court chamber musician.

Spohr’s musical talent attracted the attention of the duke, and he suggested that the violinist continue his education. Vyboo fell on two teachers – Viotti and the famous violinist Friedrich Eck. A request was sent to both, and both refused. Viotti referred to the fact that he had retired from musical activity and was engaged in the wine trade; Eck pointed to the continuous concert activity as an obstacle to systematic studies. But instead of himself, Eck suggested his brother Franz, also a concert virtuoso. Spohr worked with him for two years (1802-1804).

Together with his teacher, Spohr traveled to Russia. At that time they drove slowly, with long stops, which they used for lessons. Spur got a stern and demanding teacher, who began by completely changing the position of his right hand. “This morning,” Spohr writes in his diary, “April 30 (1802—L.R.) Mr. Eck began to study with me. But, alas, how many humiliations! I, who fancied myself one of the first virtuosos in Germany, could not play him a single measure that would arouse his approval. On the contrary, I had to repeat each measure at least ten times in order to finally satisfy him in any way. He especially did not like my bow, the rearrangement of which I myself now consider necessary. Of course, at first it will be difficult for me, but I hope to cope with this, as I am convinced that the rework will bring me great benefit.

It was believed that the technique of the game can be developed through intensive hours of practice. Spohr worked out 10 hours a day. “So I managed to achieve in a short time such skill and confidence in technique that for me there was nothing difficult in the then known concert music.” Later becoming a teacher, Spohr attached great importance to the health and endurance of students.

In Russia, Eck fell seriously ill, and Spohr, forced to stop his lessons, returned to Germany. The years of study are over. In 1805, Spohr settled in Gotha, where he was offered a position as concertmaster of an opera orchestra. He soon married Dorothy Scheidler, a theater singer and daughter of a musician who worked in a Gothic orchestra. His wife owned the harp superbly and was considered the best harpist in Germany. The marriage turned out to be very happy.

In 1812 Spohr performed in Vienna with phenomenal success and was offered the position of bandleader at the Theater An der Wien. In Vienna, Spohr wrote one of his most famous operas, Faust. It was first staged in Frankfurt in 1818. Spohr lived in Vienna until 1816, and then moved to Frankfurt, where he worked as a bandmaster for two years (1816-1817). He spent 1821 in Dresden, and from 1822 he settled in Kassel, where he held the post of general director of music.

During his life, Spohr made a number of long concert tours. Austria (1813), Italy (1816-1817), London, Paris (1820), Holland (1835), again London, Paris, only as a conductor (1843) – here is a list of his concert tours – this is in addition to touring Germany .

In 1847, a gala evening was held dedicated to the 25th anniversary of his work in the Kassel Orchestra; in 1852 he retired, devoting himself entirely to pedagogy. In 1857, a misfortune happened to him: he broke his arm; this forced him to stop teaching activities. The grief that befell him broke the will and health of Spohr, who was infinitely devoted to his art, and, apparently, hastened his death. He died on October 22, 1859.

Spohr was a proud man; he was especially upset if his dignity as an artist was infringed in some way. Once he was invited to a concert at the court of the King of Württemberg. Such concerts often took place during card games or court feasts. “Whist” and “I go with trump cards”, the clatter of knives and forks served as a kind of “accompaniment” to the game of some major musician. Music was regarded as a pleasant pastime that helped the digestion of the nobles. Spohr categorically refused to play unless the right environment was created.

Spohr could not stand the condescending and condescending attitude of the nobility towards people of art. He bitterly tells in his autobiography how often even first-class artists had to experience a sense of humiliation, speaking to the “aristocratic mob.” He was a great patriot and passionately desired the prosperity of his homeland. In 1848, at the height of the revolutionary events, he created a sextet with a dedication: “written … to restore the unity and freedom of Germany.”

Spohr’s statements testify to his adherence to principles, but also to the subjectivity of aesthetic ideals. Being an opponent of virtuosity, he does not accept Paganini and his trends, however, paying tribute to the violin art of the great Genoese. In his autobiography, he writes: “I listened to Paganini with great interest in two concerts given by him in Kassel. His left hand and G string are remarkable. But his compositions, as well as the style of their performance, are a strange mixture of genius with childishly naive, tasteless, which is why they both capture and repel.

When Ole Buhl, the “Scandinavian Paganini”, came to Spohr, he did not accept him as a student, because he believed that he could not instill in him his school, so alien to the virtuosic nature of his talent. And in 1838, after listening to Ole Buhl in Kassel, he writes: “His chord playing and the confidence of his left hand are remarkable, but he sacrifices, like Paganini, for the sake of his kunstshtuk, too many other things that are inherent in a noble instrument.”

Spohr’s favorite composer was Mozart (“I write little about Mozart, because Mozart is everything to me”). To the work of Beethoven, he was almost enthusiastic, with the exception of the works of the last period, which he did not understand and did not recognize.

As a violinist, Spohr was wonderful. Schleterer paints the following picture of his performance: “An imposing figure enters the stage, head and shoulders above those around him. Violin under the mouse. He approaches his console. Spohr never played by heart, not wanting to create a hint of slavish memorization of a piece of music, which he considered incompatible with the title of an artist. When entering the stage, he bowed to the audience without pride, but with a sense of dignity and calmly blue eyes looked around the assembled crowd. He held the violin absolutely freely, almost without inclination, due to which his right hand was raised relatively high. At the first sound, he conquered all listeners. The small instrument in his hands was like a toy in the hands of a giant. It is difficult to describe with what freedom, elegance and skill he owned it. Calmly, as if cast out of steel, he stood on the stage. The softness and grace of his movements were inimitable. Spur had a big hand, but it combined flexibility, elasticity and strength. The fingers could sink on the strings with the hardness of steel and at the same time were, when necessary, so mobile that in the lightest passages not a single trill was lost. There was no stroke that he did not master with the same perfection – his wide staccato was exceptional; even more striking was the sound of great power in the fort, soft and gentle in singing. Having finished the game, Spohr calmly bowed, with a smile on his face he left the stage amid a storm of incessant enthusiastic applause. The main quality of Spohr’s playing was a thoughtful and perfect transmission in every detail, devoid of any frivolities and trivial virtuosity. Nobility and artistic completeness characterized his execution; he always sought to convey those mental states that are born in the purest human breast.

The description of Schleterer is confirmed by other reviews. Spohr’s student A. Malibran, who wrote a biography of his teacher, mentions Spohr’s magnificent strokes, clarity of finger technique, the finest sound palette and, like Schleterer, emphasizes the nobility and simplicity of his playing. Spohr did not tolerate “entrances”, glissando, coloratura, avoided jumping, jumping strokes. His performance was truly academic in the highest sense of the word.

He never played by heart. Then it was no exception to the rule; many performers performed at concerts with notes on the console in front of them. However, with Spohr, this rule was caused by certain aesthetic principles. He also forced his students to play only from notes, arguing that a violinist who plays by heart reminds him of a parrot answering a learned lesson.

Very little is known about Spohr’s repertoire. In the early years, in addition to his works, he performed concertos by Kreutzer, Rode, later he limited himself mainly to his own compositions.

At the beginning of the XNUMXth century, the most prominent violinists held the violin in different ways. For example, Ignaz Frenzel pressed the violin to his shoulder with his chin to the left of the tailpiece, and Viotti to the right, that is, as is customary now; Spohr rested his chin on the bridge itself.

The name of Spohr is associated with some innovations in the field of violin playing and conducting. So, he is the inventor of the chin rest. Even more significant is his innovation in the art of conducting. He is credited with the use of the wand. In any case, he was one of the first conductors to use a baton. In 1810, at the Frankenhausen Music Festival, he conducted a stick rolled out of paper, and this hitherto unknown way of leading the orchestra plunged everyone into amazement. The musicians of Frankfurt in 1817 and London in the 1820s met the new style with no less bewilderment, but very soon they began to understand its advantages.

Spohr was a teacher of European renown. Students came to him from all over the world. He formed a kind of home conservatory. Even from Russia a serf named Encke was sent to him. Spohr has educated more than 140 major violin soloists and concertmasters of orchestras.

Spohr’s pedagogy was very peculiar. He was extremely loved by his students. Strict and demanding in the classroom, he became sociable and affectionate outside the classroom. Joint walks around the city, country trips, picnics were common. Spohr walked, surrounded by a crowd of his pets, went in for sports with them, taught them to swim, kept himself simple, although he never crossed the line when intimacy turns into familiarity, reducing the authority of the teacher in the eyes of the students.

He developed in the student an exceptionally responsible attitude to the lessons. I worked with a beginner every 2 days, then moved on to 3 lessons a week. At the last norm, the student remained until the end of classes. Mandatory for all students was to play in the ensemble and orchestra. “A violinist who has not received orchestral skills is like a trained canary who screams to the point of hoarseness from a learned thing,” wrote Spohr. He personally directed the playing in the orchestra, practicing orchestral skills, strokes, and techniques.

Schleterer left a description of Spohr’s lesson. He usually sat in the middle of the room in an armchair so that he could see the student, and always with a violin in his hands. During classes, he often played along with the second voice or, if the student did not succeed in some place, he showed on the instrument how to perform it. The students claimed that playing with Spurs was a real pleasure.

Spohr was especially picky about intonation. Not a single dubious note escaped his sensitive ear. Hearing it, right there, at the lesson, calmly, methodically achieved crystal clearness.

Spohr fixed his pedagogical principles in the “School”. It was a practical study guide that did not pursue the goal of progressive accumulation of skills; it contained aesthetic views, the views of its author on violin pedagogy, allowing you to see that its author was in the position of artistic education of the student. He was repeatedly blamed for the fact that he “could not” separate “technique” from “music” in his “School”. In fact, Spurs did not and could not set such a task. Spohr’s contemporary violin technique has not yet reached the point of combining artistic principles with technical ones. The synthesis of artistic and technical moments seemed unnatural to the representatives of normative pedagogy of the XNUMXth century, who advocated abstract technical training.

Spohr’s “school” is already outdated, but historically it was a milestone, as it outlined the path to that artistic pedagogy, which in the XNUMXth century found its highest expression in the work of Joachim and Auer.

L. Raaben