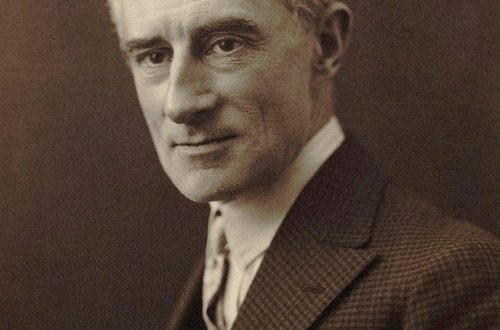

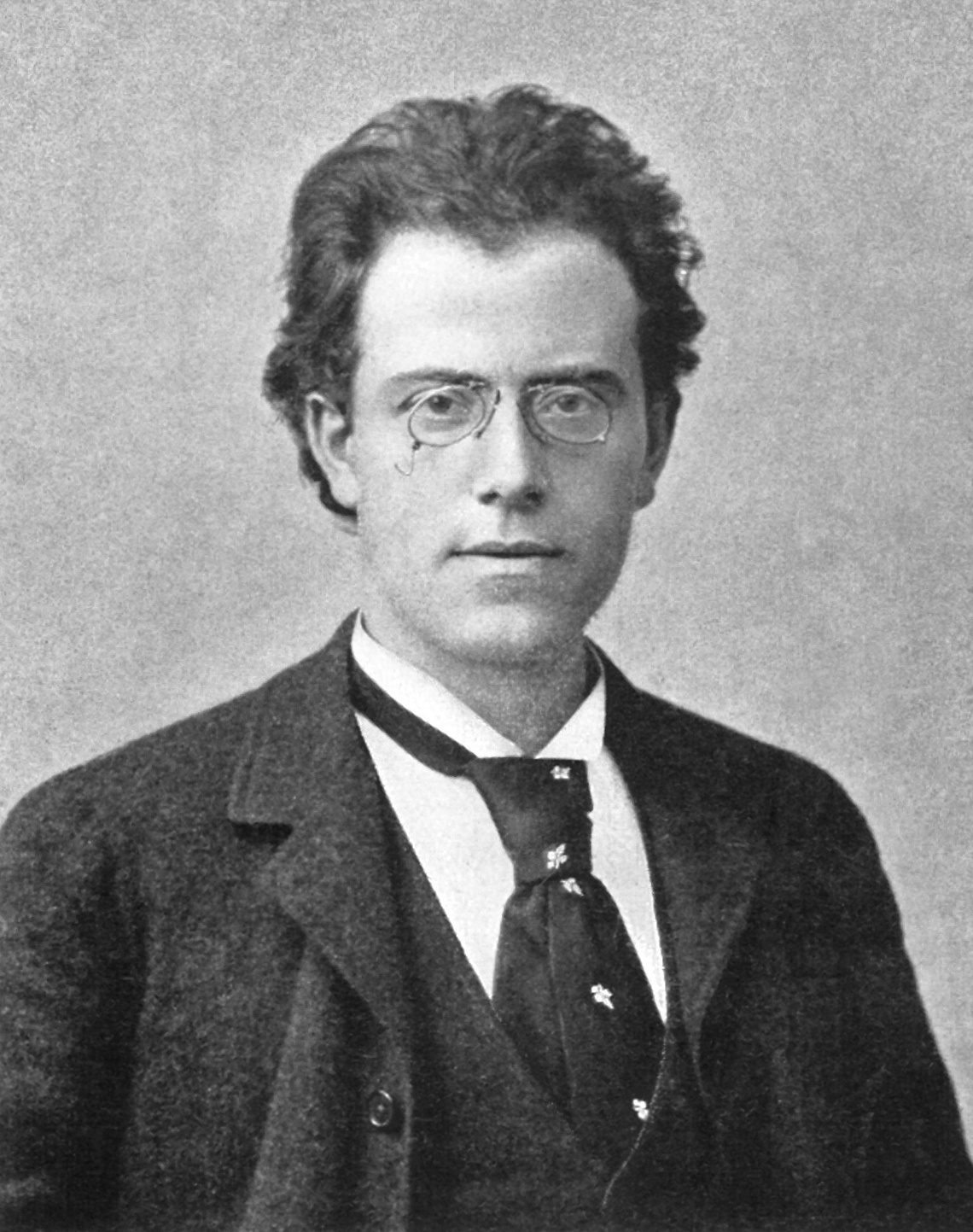

Gustav Mahler |

Gustav Mahler

A man who embodied the most serious and pure artistic will of our time. T. Mann

The great Austrian composer G. Mahler said that for him “to write a symphony means to build a new world with all the means of the available technology. All my life I have been composing music about only one thing: how can I be happy if another being suffers somewhere else. With such ethical maximalism, the “building of the world” in music, the achievement of a harmonious whole becomes the most difficult, hardly solvable problem. Mahler, in essence, completes the tradition of philosophical classical-romantic symphonism (L. Beethoven – F. Schubert – J. Brahms – P. Tchaikovsky – A. Bruckner), which seeks to answer the eternal questions of being, to determine the place of man in the world.

At the turn of the century, the understanding of human individuality as the highest value and “receptacle” of the entire universe experienced a particularly deep crisis. Mahler felt it keenly; and any of his symphonies is a titanic attempt to find harmony, an intense and each time unique process of searching for the truth. Mahler’s creative search led to a violation of established ideas about beauty, to apparent formlessness, incoherence, eclecticism; the composer erected his monumental concepts as if from the most heterogeneous “fragments” of the disintegrated world. This search was the key to preserving the purity of the human spirit in one of the most difficult eras in history. “I am a musician who wanders in the desert night of modern musical craft without a guiding star and is in danger of doubting everything or going astray,” wrote Mahler.

Mahler was born into a poor Jewish family in the Czech Republic. His musical abilities showed up early (at the age of 10 he gave his first public concert as a pianist). At the age of fifteen, Mahler entered the Vienna Conservatory, took composition lessons from the largest Austrian symphonist Bruckner, and then attended courses in history and philosophy at the University of Vienna. Soon the first works appeared: sketches of operas, orchestral and chamber music. Since the age of 20, Mahler’s life has been inextricably linked with his work as a conductor. At first – opera houses of small towns, but soon – the largest musical centers in Europe: Prague (1885), Leipzig (1886-88), Budapest (1888-91), Hamburg (1891-97). Conducting, which Mahler devoted himself to with no less enthusiasm than composing music, absorbed almost all of his time, and the composer worked on major works in the summer, free from theatrical duties. Very often the idea of a symphony was born from a song. Mahler is the author of several vocal “cycles, the first of which is “Songs of a Wandering Apprentice”, written in his own words, makes one recall F. Schubert, his bright joy of communicating with nature and the sorrow of a lonely, suffering wanderer. From these songs grew the First Symphony (1888), in which the primordial purity is obscured by the grotesque tragedy of life; the way to overcome darkness is to restore unity with nature.

In the following symphonies, the composer is already cramped within the framework of the classical four-part cycle, and he expands it, and uses the poetic word as the “carrier of the musical idea” (F. Klopstock, F. Nietzsche). The Second, Third and Fourth symphonies are connected with the cycle of songs “Magic Horn of a Boy”. The Second Symphony, about the beginning of which Mahler said that here he “buries the hero of the First Symphony”, ends with the affirmation of the religious idea of the resurrection. In the Third, a way out is found in the communion with the eternal life of nature, understood as the spontaneous, cosmic creativity of vital forces. “I am always very offended by the fact that most people, when talking about“ nature ”, always think about flowers, birds, forest aroma, etc. No one knows God Dionysus, the great Pan.”

In 1897, Mahler became the chief conductor of the Vienna Court Opera House, 10 years of work in which became an era in the history of opera performance; in the person of Mahler, a brilliant musician-conductor and director-director of the performance were combined. “For me, the greatest happiness is not that I have reached an outwardly brilliant position, but that I have now found a homeland, my family“. Among the creative successes of the stage director Mahler are operas by R. Wagner, K. V. Gluck, W. A. Mozart, L. Beethoven, B. Smetana, P. Tchaikovsky (The Queen of Spades, Eugene Onegin, Iolanthe) . In general, Tchaikovsky (like Dostoevsky) was somewhat close to the nervous-impulsive, explosive temperament of the Austrian composer. Mahler was also a major symphony conductor who toured in many countries (he visited Russia three times). The symphonies created in Vienna marked a new stage in his creative path. The fourth, in which the world is seen through children’s eyes, surprised the listeners with a balance that was not characteristic of Mahler before, a stylized, neoclassical appearance and, it seemed, a cloudless idyllic music. But this idyll is imaginary: the text of the song underlying the symphony reveals the meaning of the whole work – these are just a child’s dreams of heavenly life; and among the melodies in the spirit of Haydn and Mozart, something dissonantly broken sounds.

In the next three symphonies (in which Mahler does not use poetic texts), the coloring is generally overshadowed – especially in the Sixth, which received the title “Tragic”. The figurative source of these symphonies was the cycle “Songs about Dead Children” (on the line by F. Rückert). At this stage of creativity, the composer seems to be no longer able to find solutions to contradictions in life itself, in nature or religion, he sees it in the harmony of classical art (the finals of the Fifth and Seventh are written in the style of the classics of the XNUMXth century and contrast sharply with the previous parts).

Mahler spent the last years of his life (1907-11) in America (only when he was already seriously ill, he returned to Europe for treatment). Uncompromisingness in the fight against routine at the Vienna Opera complicated Mahler’s position, led to real persecution. He accepts an invitation to the post of conductor of the Metropolitan Opera (New York), and soon becomes the conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

In the works of these years, the thought of death is combined with a passionate thirst to capture all earthly beauty. In the Eighth Symphony – “a symphony of a thousand participants” (enlarged orchestra, 3 choirs, soloists) – Mahler tried in his own way to translate the idea of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony: the achievement of joy in universal unity. “Imagine that the universe begins to sound and ring. It is no longer human voices that sing, but circling suns and planets,” the composer wrote. The symphony uses the final scene of “Faust” by J. W. Goethe. Like the finale of a Beethoven symphony, this scene is the apotheosis of affirmation, the achievement of an absolute ideal in classical art. For Mahler, following Goethe, the highest ideal, fully achievable only in an unearthly life, is “eternally feminine, that which, according to the composer, attracts us with mystical power, that every creation (maybe even stones) with unconditional certainty feels like the center of his being. Spiritual kinship with Goethe was constantly felt by Mahler.

Throughout the entire career of Mahler, the cycle of songs and the symphony went hand in hand and, finally, fused together in the symphony-cantata Song of the Earth (1908). Embodying the eternal theme of life and death, Mahler turned this time to Chinese poetry of the XNUMXth century. Expressive flashes of drama, chamber-transparent (related to the finest Chinese painting) lyrics and – quiet dissolution, departure into eternity, reverent listening to silence, expectation – these are the features of the late Mahler’s style. The “epilogue” of all creativity, the farewell was the Ninth and unfinished Tenth symphonies.

Concluding the age of romanticism, Mahler proved to be the forerunner of many phenomena in the music of our century. The aggravation of emotions, the desire for their extreme manifestation will be picked up by the expressionists – A. Schoenberg and A. Berg. The symphonies of A. Honegger, the operas of B. Britten bear the imprint of Mahler’s music. Mahler had a particularly strong influence on D. Shostakovich. Ultimate sincerity, deep compassion for each person, breadth of thinking make Mahler very, very close to our tense, explosive time.

K. Zenkin