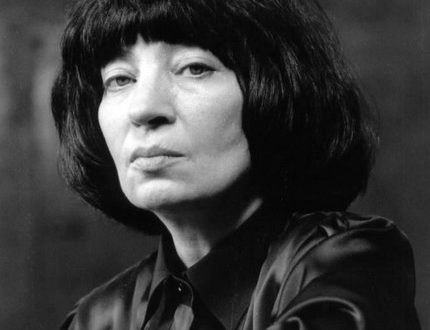

Evgeny Gedeonovich Mogilevsky |

Evgeny Mogilevsky

Evgeny Gedeonovich Mogilevsky is from a musical family. His parents were teachers at the Odessa Conservatory. Mother, Serafima Leonidovna, who once studied with G. G. Neuhaus, from the very beginning completely took care of her son’s musical education. Under her supervision, he sat down at the piano for the first time (this was in 1952, the lessons were held within the walls of the famous Stolyarsky school) and she, at the age of 18, graduated from this school. “It is believed that it is not easy for parents who are musicians to teach their children, and for children to study under the supervision of their relatives,” Mogilevsky says. “Perhaps this is so. Only I didn’t feel it. When I came to my mother’s class or when we worked at home, there was a teacher and a student next to each other – and nothing more. Mom was constantly looking for something new – techniques, teaching methods. I was always interested in her…”

- Piano music in the Ozon online store →

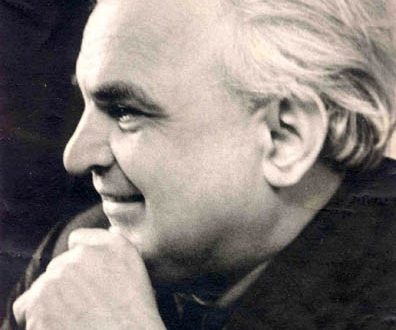

Since 1963 Mogilevsky in Moscow. For some time, unfortunately short, he studied with G. G. Neuhaus; after his death, with S. G. Neuhaus and, finally, with Y. I. Zak. “From Yakov Izrailevich I learned a lot of what I lacked at that time. Speaking in the most general form, he disciplined my performing nature. Accordingly, my game. Communication with him, even if it was not easy for me at some moments, was of great benefit. I did not stop studying with Yakov Izrailevich even after graduating, remaining in his class as an assistant.

Ever since childhood, Mogilevsky got used to the stage – at the age of nine he played in front of an audience for the first time, at eleven he performed with an orchestra. The beginning of his artistic career was reminiscent of similar biographies of child prodigies, fortunately, only the beginning. Geeks are usually “enough” for a short time, for several years; Mogilevsky, on the contrary, made more and more progress every year. And when he was nineteen, his fame in musical circles became universal. This happened in 1964, in Brussels, at the Queen Elizabeth Competition.

He received the first prize in Brussels. The victory was won in a competition that has long been considered one of the most difficult: in the capital of Belgium, for a random reason, you can do not take prize place; you can’t take it by accident. Among Mogilevsky’s competitors there were quite a few excellently trained pianists, including several exceptionally high-class masters. It is unlikely that he would have become the first if competitions were held according to the formula “whose technique is better”. Everything this time decided otherwise – the charm of his talent.

Ya. I. Zak once said about Mogilevsky that there is “a lot of personal charm” in his game (Zak Ya. In Brussels // Sov. Music. 1964. No. 9. P. 72.). G. G. Neuhaus, even meeting the young man for a short time, managed to notice that he was “extremely handsome, has great human charm, in harmony with his natural artistry” (Neigauz G. G. Reflections of a jury member // Neugauz G. G. Reflections, memoirs, diaries. Selected articles. Letters to parents. P. 115.). Both Zach and Neuhaus spoke essentially about the same thing, albeit in different words. Both meant that if charm is a precious quality even in simple, “everyday” communication between people, then how important is it for an artist – someone who goes on stage, communicates with hundreds, thousands of people. Both saw that Mogilevsky was endowed with this happy (and rare!) gift from birth. This “personal charm,” as Zach put it, brought Mogilevsky success in his early childhood performances; later decided his artistic fate in Brussels. It still attracts people to his concerts to this day.

(Earlier, more than once it was said about the general thing that brings the concert and theatrical scenes together. “Do you know such actors who only have to appear on the stage, and the audience already loves them?” wrote K. S. Stanislavsky. “For what?. For that elusive property that we call charm. This is the inexplicable attractiveness of the whole being of an actor, in which even flaws turn into virtues … ” (Stanislavsky K.S. Work on oneself in the creative process of incarnation // Collected works – M., 1955. T. 3. S. 234.))

The charm of Mogilevsky as a concert performer, if we leave aside the “elusive” and “inexplicable”, is already in the very manner of his intonation: soft, affectionately insinuating; the pianist’s intonations-complaints, intonations-sighs, “notes” of tender requests, prayers are especially expressive. Examples include Mogilevsky’s performance of the beginning of Chopin’s Fourth Ballade, a lyrical theme from the Third movement of Schumann’s Fantasy in C major, which is also among his successes; one can recall a lot in the Second Sonata and the Third Concerto of Rachmaninov, in the works of Tchaikovsky, Scriabin and other authors. His piano voice is also charming – sweet-sounding, sometimes charmingly languid, like that of a lyrical tenor in an opera – a voice that seems to envelop with bliss, warmth, fragrant timbre colors. (Sometimes, something emotionally sultry, fragrant, thickly spicy in color – seems to be in Mogilevsky’s sound sketches, isn’t this their special charm?)

Finally, the artist’s performing style is also attractive, the way he behaves in front of people: his appearances on the stage, poses during the game, gestures. In him, in all his appearance behind the instrument, there is both an inner delicacy and good breeding, which causes an involuntary disposition towards him. Mogilevsky on his clavirabends is not only pleasant to listen to, it is pleasant to look at him.

The artist is especially good in the romantic repertoire. He has long won recognition for himself in such works as Schumann’s Kreisleriana and F sharp minor novelta, Liszt’s sonata in B minor, etudes and Petrarch’s Sonnets, Fantasia and Fugue on the themes of Liszt’s opera The Prophet – Busoni, impromptu and Schubert’s “Musical Moments”, sonatas and Chopin’s Second Piano Concerto. It is in this music that his impact on the audience is most noticeable, his stage magnetism, his magnificent ability to infect their experiences of others. It happens that some time passes after the next meeting with a pianist and you start to think: was there not more brightness in his stage statements than depth? More sensual charm than what is understood in music as philosophy, spiritual introspection, immersion in oneself? .. It is only curious that all these considerations come to mind laterwhen Mogilevsky conchaet play.

It is more difficult for him with the classics. Mogilevsky, as soon as they spoke to him on this topic before, usually answered that Bach, Scarlatti, Hynd, Mozart were not “his” authors. (In recent years, however, the situation has changed somewhat – but more on that later.) These are, obviously, the peculiarities of the pianist’s creative “psychology”: it is easier for him open up in post-Beethoven music. However, another thing also matters – the individual properties of his performing technique.

The bottom line is that in Mogilevsky it always manifested itself from the most advantageous side precisely in the romantic repertoire. For pictorial decorativeness, “color” dominate in it over the drawing, a colorful spot – over a graphically accurate outline, a thick sound stroke – over a dry, pedalless stroke. The big takes precedence over the small, the poetic “general” – over the particular, the detail, the jewelry-made detail.

It happens that in Mogilevsky’s playing one can feel some sketchiness, for example, in his interpretation of Chopin’s preludes, etudes, etc. The pianist’s sound contours seem to be slightly blurred at times (Ravel’s “Night Gaspar”, Scriabin’s miniatures, Debussy’s “Images”, “Pictures at an Exhibition »Mussorgsky, etc.) – just as it can be seen in the sketches of impressionist artists. Undoubtedly, in the music of a certain type – that, first of all, that was born of a spontaneous romantic impulse – this technique is both attractive and effective in its own way. But not in the classics, not in the clear and transparent sound constructions of the XNUMXth century.

Mogilevsky does not stop working today on “finishing” his skills. This is also felt by that he plays – what authors and works he refers to – and therefore, as he looks now on the concert stage. It is symptomatic that several of Haydn’s sonatas and Mozart’s piano concertos re-learned appeared in his programs of the mid and late eighties; entered these programs and firmly established in them such plays as “Elegy” and “Tambourine” by Rameau-Godowsky, “Giga” by Lully-Godowsky. And further. Beethoven’s compositions began to sound more and more often at his evenings – piano concertos (all five), 33 variations on the Waltz by Diabelli, Twenty-ninth, Thirty-second and some other sonatas, Fantasia for piano, choir and orchestra, etc. Of course, it gives know the attraction to the classics that comes with the years to every serious musician. But not only. Evgeny Gedeonovich’s constant desire to improve, improve the “technology” of his game also has an effect. And the classics in this case are indispensable …

“Today I face problems that I didn’t pay enough attention to in my youth,” says Mogilevsky. Knowing in general terms the creative biography of the pianist, it is not difficult to guess what is hidden behind these words. The fact is that he, a generously gifted person, played the instrument from childhood without much effort; it had both its positive and negative sides. Negative – because there are achievements in art that acquire value only as a result of the artist’s stubborn overcoming of the “resistance of the material.” Tchaikovsky said that creative luck often has to be “worked out”. The same, of course, in the profession of a performing musician.

Mogilevsky needs to improve his playing technique, achieving greater subtlety of external decoration, refinement in the development of details, not only in order to gain access to some masterpieces of the classics – Scarlatti, Haydn or Mozart. This is also required by the music that he usually performs. Even if he performs, admittedly, very successfully, as, for example, Medtner’s E minor sonata, or Bartok’s sonata (1926), Liszt’s First Concerto or Prokofiev’s Second. The pianist knows—and today better than ever before—that whoever wants to rise above the level of “good” or even “very good” playing is required these days to have impeccable, filigree performance skills. That is just what can only be “tortured out”.

* * *

In 1987, an interesting event took place in the life of Mogilevsky. He was invited as a member of the jury at the Queen Elizabeth Competition in Brussels – the same one where he once, 27 years ago, won the gold medal. He remembered a lot, thought about a lot when he was at the table of a jury member – and about the path he had traveled since 1964, about what had been done, achieved during this time, and about what had not been done yet, had not been implemented to the extent as you would like. Such thoughts, which are sometimes difficult to formulate and generalize accurately, are always important for people of creative work: bringing restlessness and anxiety into the soul, they are like impetuses that encourage them to move forward.

In Brussels, Mogilevsky heard many young pianists from around the world. Thus he received, as he says, an idea of some of the characteristic trends in modern piano performance. In particular, it seemed to him that the anti-romantic line now dominates more and more clearly.

At the end of the XNUMXs, there were other interesting artistic events and meetings for Mogilev; there were many bright musical impressions that somehow influenced him, excited him, left a trace in his memory. For example, he does not get tired of sharing enthusiastic thoughts inspired by Evgeny Kissin’s concerts. And it can be understood: in art, sometimes an adult can draw, learn from a child no less than a child from an adult. Kissin generally impresses Mogilevsky. Perhaps he feels in him something akin to himself – in any case, if we keep in mind the time when he himself began his stage career. Yevgeny Gedeonovich likes the young pianist’s playing also because it runs counter to the “anti-romantic trend” he noticed in Brussels.

…Mogilevsky is an active concert performer. He has always been loved by the public, from his very first steps on the stage. We love him for his talent, which, despite all the changes in trends, styles, tastes and fashions, has been and will remain the “number one” value in art. Everything can be achieved, achieved, “extorted” except for the right to be called Talent. (“You can teach how to add meters, but you cannot learn how to add metaphors,” Aristotle once said.) Mogilevsky, however, does not doubt this right.

G. Tsypin