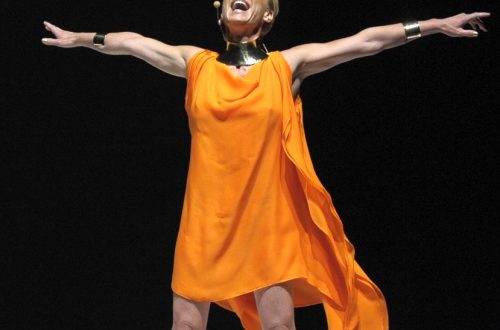

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf |

Elizabeth Schwarzkopf

Among the vocalists of the second half of the XNUMXth century, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf occupies a special place, comparable only to Maria Callas. And today, decades later from the moment when the singer last appeared before the public, for admirers of the opera, her name still personifies the standard of opera singing.

Although the history of singing culture knows many examples of how artists with poor vocal abilities managed to achieve significant artistic results, the example of Schwarzkopf seems to be truly unique. In the press, there were often confessions like this: “If in those years when Elisabeth Schwarzkopf was just starting her career, someone had told me that she would become a great singer, I would honestly doubt it. She achieved a real miracle. Now I am firmly convinced that if other singers had at least a particle of her fantastic performance, artistic sensitivity, obsession with art, then we would obviously have entire opera troupes consisting only of stars of the first magnitude.

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf was born in the Polish town of Jarocin, near Poznan, on December 9, 1915. From an early age she was fond of music. In a rural school where her father taught, the girl participated in small productions that took place near another Polish city – Legnica. The daughter of a Greek and Latin teacher at a men’s school, she once even sang all the female parts in an opera composed by the students themselves.

The desire to become an artist even then, apparently, became her life goal. Elisabeth goes to Berlin and enters the Higher School of Music, which at that time was the most respected musical educational institution in Germany.

She was accepted into her class by the famous singer Lula Mys-Gmeiner. She was inclined to believe that her student had a mezzo-soprano. This mistake almost turned into a loss of voice for her. The classes did not go very well. The young singer felt that her voice was not obeying well. She quickly got tired in class. Only two years later, other vocal teachers established that Schwarzkopf was not a mezzo-soprano, but a coloratura soprano! The voice immediately sounded more confident, brighter, freer.

At the conservatory, Elizabeth did not limit herself to the course, but studied the piano and viola, managed to sing in the choir, play the glockenspiel in the student orchestra, participate in chamber ensembles, and even tried her skills in composition.

In 1938, Schwarzkopf graduated from the Berlin Higher School of Music. Six months later, the Berlin City Opera urgently needed a performer in the small role of a flower girl in Wagner’s Parsifal. The role had to be learned in a day, but this did not bother Schwarzkopf. She managed to make a favorable impression on the audience and the theater administration. But, apparently, no more: she was accepted into the troupe, but over the next years she was assigned almost exclusively episodic roles – in a year of work in the theater, she sang about twenty small roles. Only occasionally did the singer have a chance to go on stage in real roles.

But one day the young singer was lucky: in the Cavalier of the Roses, where she sang Zerbinetta, she was heard and appreciated by the famous singer Maria Ivogun, who herself shone in this part in the past. This meeting played an important role in Schwarzkopf’s biography. A sensitive artist, Ivogün saw a real talent in Schwarzkopf and began to work with her. She initiated her into the secrets of stage technique, helped broaden her horizons, introduced her to the world of chamber vocal lyrics, and most importantly, awakened her love for chamber singing.

After classes with Ivogün Schwarzkopf, he begins to gain more and more fame. The end of the war, it seemed, should have contributed to this. The directorate of the Vienna Opera offered her a contract, and the singer made bright plans.

But suddenly the doctors discovered tuberculosis in the artist, which almost made her forget about the stage forever. Nevertheless, the disease was overcome.

In 1946, the singer made her debut at the Vienna Opera. The public was able to truly appreciate Schwarzkopf, who quickly became one of the leading soloists of the Vienna Opera. In a short time she performed the parts of Nedda in Pagliacci by R. Leoncavallo, Gilda in Verdi’s Rigoletto, Marcellina in Beethoven’s Fidelio.

At the same time, Elizabeth had a happy meeting with her future husband, the famous impresario Walter Legge. One of the greatest connoisseurs of the musical art of our time, at that time he was obsessed with the idea of spreading music with the help of a gramophone record, which then began to transform into a long-playing one. Only recording, Legge argued, is capable of turning the elitist into the mass, making the achievements of the greatest interpreters accessible to everyone; otherwise it simply does not make sense to put on expensive performances. It is to him that we largely owe the fact that the art of many great conductors and singers of our time remains with us. “Who would I be without him? Elisabeth Schwarzkopf said much later. – Most likely, a good soloist of the Vienna Opera … “

In the late 40s, Schwarzkopf records began to appear. One of them somehow came to the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler. The illustrious maestro was so delighted that he immediately invited her to participate in the performance of Brahms’ German Requiem at the Lucerne Festival.

The year 1947 became a milestone for the singer. Schwarzkopf goes on a responsible international tour. She performs at the Salzburg Festival, and then – on the stage of the London theater “Covent Garden”, in Mozart’s operas “The Marriage of Figaro” and “Don Giovanni”. Critics of “foggy Albion” unanimously call the singer the “discovery” of the Vienna Opera. So Schwarzkopf comes to international fame.

From that moment on, her whole life is an uninterrupted chain of triumphs. Performances and concerts in the largest cities of Europe and America follow each other.

In the 50s, the artist settled in London for a long time, where she often performed on the stage of the Covent Garden Theatre. In the capital of England, Schwarzkopf met the outstanding Russian composer and pianist N.K. Medtner. Together with him, she recorded a number of romances on the disc, and repeatedly performed his compositions in concerts.

In 1951, together with Furtwängler, she participated in the Bayreuth Festival, in a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and in the “revolutionary” production of “Rheingold d’Or” by Wieland Wagner. At the same time, Schwarzkopf participates in the performance of Stravinsky’s opera “The Rake’s Adventures” together with the author, who was behind the console. Teatro alla Scala gave her the honor of performing the part of Mélisande on the fiftieth anniversary of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. Wilhelm Furtwängler as a pianist recorded Hugo Wolf’s songs with her, Nikolai Medtner – his own romances, Edwin Fischer – Schubert’s songs, Walter Gieseking – Mozart’s vocal miniatures and arias, Glen Gould – songs of Richard Strauss. In 1955, from the hands of Toscanini, she accepted the Golden Orpheus prize.

These years are the flowering of the singer’s creative talent. In 1953, the artist made her debut in the United States – first with a concert program in New York, later – on the San Francisco opera stage. Schwarzkopf performs in Chicago and London, Vienna and Salzburg, Brussels and Milan. On the stage of Milan’s “La Scala” for the first time she shows one of her most brilliant roles – the Marshall in “Der Rosenkavalier” by R. Strauss.

“A truly classic creation of modern musical theater was its Marshall, a noble lady of Viennese society in the middle of the XNUMXth century,” writes V.V. Timokhin. – Some directors of “The Knight of the Roses” at the same time considered it necessary to add: “A woman is already fading, who has passed not only the first, but also the second youth.” And this woman loves and is loved by the youth Octavian. What, it would seem, is the scope for embodying the drama of the aging Marshal’s wife as touchingly and penetratingly as possible! But Schwarzkopf did not follow this path (it would be more correct to say, only along this path), offering her own vision of the image, in which the audience was captivated precisely by the subtle transfer of all psychological, emotional nuances in the complex range of experiences of the heroine.

She is delightfully beautiful, full of quivering tenderness and true charm. Listeners immediately remembered her Countess Almaviva in The Marriage of Figaro. And although the main emotional tone of the image of the Marshall is already different, Mozart’s lyricism, grace, subtle grace remained its main feature.

Light, amazingly beautiful, silvery timbre, Schwarzkopf’s voice possessed an amazing ability to cover any thickness of orchestral masses. Her singing always remained expressive and natural, no matter how complex the vocal texture was. Her artistry and sense of style were impeccable. That is why the artist’s repertoire was striking in variety. She equally succeeded in such dissimilar roles as Gilda, Mélisande, Nedda, Mimi, Cio-Cio-San, Eleanor (Lohengrin), Marceline (Fidelio), but her highest achievements are associated with the interpretation of operas by Mozart and Richard Strauss.

There are parties that Schwarzkopf made, as they say, “her own”. In addition to the Marshall, this is Countess Madeleine in Strauss’s Capriccio, Fiordiligi in Mozart’s All They Are, Elvira in Don Giovanni, the Countess in Le nozze di Figaro. “But, obviously, only vocalists can truly appreciate her work on phrasing, the jewelry finish of every dynamic and sound nuance, her amazing artistic finds, which she squanders with such effortless ease,” says V.V. Timokhin.

In this regard, the case, which was told by the husband of the singer Walter Legge, is indicative. Schwarzkopf has always admired Callas’ craftsmanship. Having heard Callas in La Traviata in 1953 in Parma, Elisabeth decided to leave the role of Violetta forever. She considered that she could not play and sing this part better. Kallas, in turn, highly appreciated Schwarzkopf’s performance skills.

After one of the recording sessions with the participation of Callas, Legge noticed that the singer often repeats a popular phrase from the Verdi opera. At the same time, he got the impression that she was painfully looking for the right option and could not find it.

Unable to stand it, Kallas turned to Legge: “When will Schwarzkopf be here today?” He replied that they agreed to meet at a restaurant to have lunch. Before Schwarzkopf appeared in the hall, Kallas, with her characteristic expansiveness, rushed towards her and began to hum the ill-fated melody: “Listen, Elisabeth, how do you do it here, in this place, such a fading phrase?” Schwarzkopf was at first confused: “Yes, but not now, after, let’s have lunch first.” Callas resolutely insisted on her own: “No, right now this phrase haunts me!” Schwarzkopf relented – lunch was set aside, and here, in the restaurant, an unusual lesson began. The next day, at ten o’clock in the morning, the phone rang in Schwarzkopf’s room: on the other end of the wire, Callas: “Thank you, Elisabeth. You helped me so much yesterday. I finally found the diminuendo I needed.”

Schwarzkopf always willingly agreed to perform in concerts, but did not always have time to do so. After all, in addition to the opera, she also participated in the productions of operettas by Johann Strauss and Franz Lehar, in the performance of vocal and symphonic works. But in 1971, leaving the stage, she devoted herself entirely to song, romance. Here she preferred the lyrics of Richard Strauss, but did not forget other German classics – Mozart and Beethoven, Schumann and Schubert, Wagner, Brahms, Wolf …

In the late 70s, after the death of her husband, Schwarzkopf left the concert activity, having given before that farewell concerts in New York, Hamburg, Paris and Vienna. The source of her inspiration faded, and in memory of the man who gave her gift to the whole world, she stopped singing. But she did not part with art. “Genius is, perhaps, an almost infinite ability to work without rest,” she likes to repeat the words of her husband.

The artist devotes herself to vocal pedagogy. In different cities of Europe, she conducts seminars and courses, which attract young singers from all over the world. “Teaching is an extension of singing. I do what I have done all my life; worked on beauty, truthfulness of sound, fidelity to style and expressiveness.

PS Elisabeth Schwarzkopf passed away on the night of August 2-3, 2006.