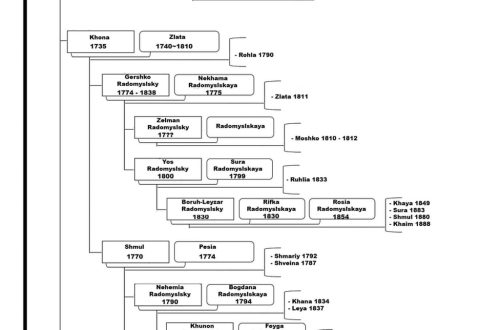

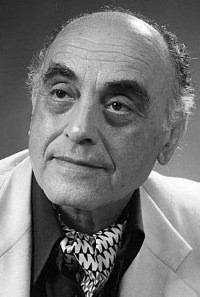

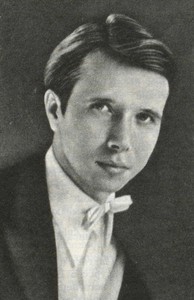

Mikhail Vasilievich Pletnev |

Mikhail Pletnev

Mikhail Vasilyevich Pletnev attracts close attention of both specialists and the general public. He’s really popular; It would not be an exaggeration to say that in this respect he stands somewhat apart in the long line of laureates of international competitions of recent years. The pianist’s performances are almost always sold out and there is no indication that this situation may change.

Pletnev is a complex, extraordinary artist, with his own characteristic, memorable face. You can admire him or not, proclaim him the leader of modern pianistic art or completely, “out of the blue”, reject everything that he does (it happens), in any case, acquaintance with him does not leave people indifferent. And that’s what matters, in the end.

… He was born on April 14, 1957 in Arkhangelsk, in a family of musicians. Later he moved with his parents to Kazan. His mother, a pianist by education, worked at one time as an accompanist and teacher. My father was an accordion player, taught at various educational institutions, and for a number of years served as an assistant professor at the Kazan Conservatory.

Misha Pletnev discovered his ability to music early – from the age of three he reached for the piano. Kira Alexandrovna Shashkina, a teacher at the Kazan Special Music School, began to teach him. Today he remembers Shashkina only with a kind word: “A good musician … In addition, Kira Alexandrovna encouraged my attempts to compose music, and I can only say a big thank you to her for this.”

At the age of 13, Misha Pletnev moved to Moscow, where he became a student of the Central Music School in the class of E. M. Timakin. A prominent teacher, who opened the way to the stage for many subsequently famous concertgoers, E. M. Timakin helped Pletnev in many ways. “Yes, yes, very much. And almost in the first place – in the organization of the motor-technical apparatus. A teacher who thinks deeply and interestingly, Evgeny Mikhailovich is excellent at doing this. Pletnev stayed in Timakin’s class for several years, and then, when he was a student, he moved to the professor of the Moscow Conservatory, Ya. V. Flier.

Pletnev did not have easy lessons with Flier. And not only because of the high demands of Yakov Vladimirovich. And not because they represented different generations in art. Their creative personalities, characters, temperaments were too dissimilar: an ardent, enthusiastic, despite his age, professor, and a student who looked almost his complete opposite, almost an antipode … But Flier, as they say, was not easy with Pletnev. It was not easy because of his difficult, stubborn, intractable nature: he had his own and independent point of view on almost everything, he did not leave discussions, but, on the contrary, openly looked for them – they took little on faith without evidence. Eyewitnesses say that Flier sometimes had to rest for a long time after lessons with Pletnev. Once, as if he said that he spends as much energy on one lesson with him as he spends on two solo concerts … All this, however, did not interfere with the deep affection of the teacher and student. Perhaps, on the contrary, it strengthened her. Pletnev was the “swan song” of Flier the teacher (unfortunately, he did not have to live up to the loudest triumph of his pupil); the professor spoke of him with hope, admiration, believed in his future: “You see, if he plays to the best of his ability, you will really hear something unusual. This does not happen often, believe me – I have enough experience … ” (Gornostaeva V. Disputes around the name // Soviet culture. 1987. March 10.).

And one more musician must be mentioned, listing those to whom Pletnev is indebted, with whom he had quite long creative contacts. This is Lev Nikolaevich Vlasenko, in whose class he graduated from the conservatory in 1979, and then an assistant trainee. It is interesting to recall that this talent is in many respects a different creative configuration than that of Pletnev: his generous, open emotionality, wide performing scope – all this betrays in him a representative of a different artistic type. However, in art, as in life, opposites often converge, turn out to be useful and necessary to each other. There are many examples of this in pedagogical everyday life, and in the practice of ensemble music making, etc., etc.

… Back in his school years, Pletnev took part in the International Music Competition in Paris (1973) and won the Grand Prix. In 1977 he won the first prize at the All-Union Piano Competition in Leningrad. And then one of the main, decisive events of his artistic life followed – a golden triumph at the Sixth Tchaikovsky Competition (1978). This is where his path to great art begins.

It is noteworthy that he entered the concert stage as an almost complete artist. If usually in such cases one has to see how an apprentice gradually grows into a master, an apprentice into a mature, independent artist, then with Pletnev it was not possible to observe this. The process of creative maturation turned out to be here, as it were, curtailed, hidden from prying eyes. The audience immediately got acquainted with a well-established concert player – calm and prudent in his actions, perfectly in control of himself, firmly knowing that he wants to say and as it should be done. Nothing artistically immature, disharmonious, unsettled, student-like raw was seen in his game – although he was only 20 at that time with little and stage experience, he practically did not have.

Among his peers, he was noticeably distinguished both by the seriousness, strictness of performing interpretations, and by an extremely pure, spiritually elevated attitude to music; the latter, perhaps, disposed to him most of all … His programs of those years included the famous Beethoven’s Thirty-Second Sonata – a complex, philosophically profound musical canvas. And it is characteristic that it was this composition that happened to become one of the creative culminations of the young artist. The audience of the late seventies – early eighties is unlikely to have forgotten Arietta (the second part of the sonata) performed by Pletnev – then for the first time the young man struck her with his manner of pronouncing, as it were, in an undertone, very weighty and significant, the musical text. By the way, he has preserved this manner to this day, without losing its hypnotic effect on the audience. (There is a half-joking aphorism according to which all concert artists can be divided into two main categories; some can play well the first part of Beethoven’s Thirty-second Sonata, others can play the second part of it. Pletnev plays both parts equally well; this really rarely happens.).

In general, looking back at Pletnev’s debut, one cannot fail to emphasize that even when he was still quite young, there was nothing frivolous, superficial in his playing, nothing from empty virtuoso tinsel. With his excellent pianistic technique – elegant and brilliant – he never gave any reason to reproach himself for purely external effects.

Almost from the very first performances of the pianist, criticism spoke of his clear and rational mind. Indeed, the reflection of thought is always clearly present on what he does on the keyboard. “Not the steepness of spiritual movements, but evenness research”- this is what determines, according to V. Chinaev, the general tone of Pletnev’s art. The critic adds: “Pletnev really explores the sounding fabric – and does it flawlessly: everything is highlighted – to the smallest detail – the nuances of textured plexuses, the logic of dashed, dynamic, formal proportions emerges in the listener’s mind. The game of the analytical mind – confident, knowing, unmistakable ” (Chinaev V. Calm of clarity // Sov. music. 1985. No. 11. P. 56.).

Once in an interview published in the press, Pletnev’s interlocutor told him: “You, Mikhail Vasilievich, are considered an artist of an intellectual warehouse. Weigh in this regard the various pros and cons. Interestingly, what do you understand by intelligence in the art of music, in particular, performing? And how does the intellectual and intuitive correlate in your work?”

“First, if you will, about intuition,” he replied. — It seems to me that intuition as an ability is somewhere close to what we mean by artistic and creative talent. Thanks to intuition – let’s call it, if you like, the gift of artistic providence – a person can achieve more in art than by climbing only on a mountain of special knowledge and experience. There are many examples to support my idea. Especially in music.

But I think the question should be put a little differently. Why or one thing or other? (But, unfortunately, this is how they usually approach the problem we are talking about.) Why not a highly developed intuition plus good knowledge, good understanding? Why not intuition plus the ability to rationally comprehend the creative task? There is no better combination than this.

Sometimes you hear that the load of knowledge can to a certain extent weigh down a creative person, muffle the intuitive beginning in him … I don’t think so. Rather, on the contrary: knowledge and logical thinking give intuition strength, sharpness. Take it to a higher level. If a person subtly feels art and at the same time has the ability for deep analytical operations, he will go further in creativity than someone who relies only on instinct.

By the way, those artists who I personally particularly like in the musical and performing arts are just distinguished by a harmonious combination of the intuitive – and the rational-logical, the unconscious – and the conscious. All of them are strong both in their artistic conjecture and intellect.

… They say that when the outstanding Italian pianist Benedetti-Michelangeli was visiting Moscow (it was in the mid-sixties), he was asked at one of the meetings with the capital’s musicians – what, in his opinion, is especially important for a performer? He answered: musical-theoretical knowledge. Curious, isn’t it? And what does theoretical knowledge mean for a performer in the broadest sense of the word? This is professional intelligence. In any case, the core of it … ” (Musical life. 1986. No. 11. P. 8.).

Talk about Pletnev’s intellectualism has been going on for a long time, as noted. You can hear them both in the circles of specialists and among ordinary music lovers. As one famous writer once noted, there are conversations that, once started, do not stop … Actually, there was nothing reprehensible in these conversations themselves, unless you forget: in this case, we should not talk about Pletnev’s primitively understood “coldness” ( if he were just cold, emotionally poor, he would have nothing to do on the concert stage) and not about some kind of “thinking” about him, but about the special attitude of the artist. A special typology of talent, a special “way” to perceive and express music.

As for Pletnev’s emotional restraint, about which there is so much talk, the question is, is it worth arguing about tastes? Yes, Pletnev is a closed nature. The emotional severity of his playing can sometimes reach almost asceticism – even when he performs Tchaikovsky, one of his favorite authors. Somehow, after one of the pianist’s performances, a review appeared in the press, the author of which used the expression: “indirect lyrics” – it was both accurate and to the point.

Such, we repeat, is the artistic nature of the artist. And one can only be glad that he does not “play out”, does not use stage cosmetics. In the end, among those who really have something to say, isolation is not so rare: both in life and on stage.

When Pletnev made his debut as a concertist, a prominent place in his programs was occupied by works by J. S. Bach (Partita in B minor, Suite in A minor), Liszt (Rhapsodies XNUMX and XNUMX, Piano Concerto No. XNUMX), Tchaikovsky (Variations in F major, piano concertos), Prokofiev (Seventh Sonata). Subsequently, he successfully played a number of works by Schubert, Brahms’s Third Sonata, plays from the Years of Wanderings cycle and Liszt’s Twelfth Rhapsody, Balakirev’s Islamey, Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, the Grand Sonata, The Seasons and individual opuses by Tchaikovsky .

It is impossible not to mention his monographic evenings devoted to the sonatas of Mozart and Beethoven, not to mention the Second Piano Concerto of Saint-Saens, preludes and fugues by Shostakovich. In the 1986/1987 season Haydn’s Concerto in D Major, Debussy’s Piano Suite, Rachmaninov’s Preludes, Op. 23 and other pieces.

Persistently, with firm purposefulness, Pletnev seeks his own stylistic spheres closest to him in the world piano repertoire. He tries himself in the art of different authors, eras, trends. In some ways he also fails, but in most cases he finds what he needs. First of all, in the music of the XNUMXth century (J.S. Bach, D. Scarlatti), in the Viennese classics (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven), in some creative regions of romanticism (Liszt, Brahms). And, of course, in the writings of the authors of the Russian and Soviet schools.

More debatable is Pletnev’s Chopin (Second and Third sonatas, polonaises, ballads, nocturnes, etc.). It is here, in this music, that one begins to feel that the pianist really lacks at times the immediacy and openness of feelings; moreover, it is characteristic that in a different repertoire it never occurs to talk about it. It is here, in the world of Chopin’s poetics, that you suddenly notice that Pletnev is really not too inclined to stormy outpourings of the heart, that he, in modern terms, is not very communicative, and that there is always a certain distance between him and the audience. If the performers who, while conducting a musical “talk” with the listener, seem to be on “you” with him; Pletnev always and only on “you”.

And another important point. As you know, in Chopin, in Schumann, in the works of some other romantics, the performer is often required to have an exquisitely capricious play of moods, impulsiveness and unpredictability of spiritual movements, flexibility of psychological nuance, in short, everything that happens only to people of a certain poetic warehouse. However, Pletnev, a musician and a person, has something a little different… Romantic improvisation is not close to him either — that special freedom and looseness of the stage manner, when it seems that the work spontaneously, almost spontaneously arises under the fingers of the concert performer.

By the way, one of the highly respected musicologists, having once visited a pianist’s performance, expressed the opinion that Pletnev’s music “is being born now, this very minute” (Tsareva E. Creating a picture of the world // Sov. music. 1985. No. 11. P. 55.). Is not it? Wouldn’t it be more accurate to say that it’s the other way around? In any case, it is much more common to hear that everything (or almost everything) in Pletnev’s work is carefully thought out, organized, and built in advance. And then, with its inherent accuracy and consistency, it is embodied “in the material”. Embodied with sniper accuracy, with almost one hundred percent hit on the target. This is the artistic method. This is the style, and the style, you know, is a person.

It is symptomatic that Pletnev the performer is sometimes compared with Karpov the chess player: they find something in common in the nature and methodology of their activities, in approaches to solving the creative tasks they face, even in the purely external “picture” of what they create – one behind the keyboard piano, others at the chessboard. Performing interpretations of Pletnev are compared with the classically clear, harmonious and symmetrical constructions of Karpov; the latter, in turn, are likened to Pletnev’s sound constructions, impeccable in terms of the logic of thought and execution technique. For all the conventionality of such analogies, for all their subjectivity, they clearly carry something that attracts attention…

It is worth adding to what has been said that Pletnev’s artistic style is generally typical of the musical and performing arts of our time. In particular, that anti-improvisational stage incarnation, which has just been pointed out. Something similar can be observed in the practice of the most prominent artists of today. In this, as in many other things, Pletnev is very modern. Perhaps that is why there is such a heated debate around his art.

… He usually gives the impression of a person who is completely self-confident – both on stage and in everyday life, in communication with others. Some people like it, others don’t really like it … In the same conversation with him, fragments of which were cited above, this topic was indirectly touched upon:

– Of course, you know, Mikhail Vasilyevich, that there are artists who tend to overestimate themselves to one degree or another. Others, on the contrary, suffer from an underestimation of their own “I”. Could you comment on this fact, and it would be good from this angle: the inner self-esteem of the artist and his creative well-being. Exactly creative…

– In my opinion, it all depends on what stage of work the musician is at. At what stage. Imagine that a certain performer is learning a piece or a concert program that is new to him. So, it’s one thing to doubt at the beginning of work or even in the middle of it, when you are one more on one with music and yourself. And quite another – on stage …

While the artist is in creative solitude, while he is still in the process of work, it is quite natural for him to distrust himself, to underestimate what he has done. All this is only for the good. But when you find yourself in public, the situation changes, and fundamentally. Here, any kind of reflection, underestimation of oneself is fraught with serious troubles. Sometimes irreparable.

There are musicians who constantly torment themselves with thoughts that they will not be able to do something, they will blunder in something, they will fail somewhere; etc. And in general, they say, what should they do on the stage when there is, say, Benedetti Michelangeli in the world … It is better not to appear on the stage with such mindsets. If the listener in the hall does not feel confident in the artist, he involuntarily loses respect for him. Thus (this is the worst of all) and to his art. There is no inner conviction – there is no persuasiveness. The performer hesitates, the performer hesitates, and the audience also doubts.

In general, I would sum it up like this: doubts, underestimation of your efforts in the process of homework – and perhaps more self-confidence on the stage.

– Self-confidence, you say … It’s good if this trait is inherent in a person in principle. If she is in his nature. And if not?

“Then I don’t know. But I firmly know something else: all the preliminary work on the program that you are preparing for public display must be done with the utmost thoroughness. The conscience of the performer, as they say, must be absolutely pure. Then comes confidence. At least that’s how it is for me (Musical life. 1986. No. 11. P. 9.).

… In Pletnev’s game, attention is always drawn to the thoroughness of the exterior finish. The jewelery chasing of details, the impeccable correctness of lines, the clarity of sound contours, and the strict alignment of proportions are striking. Actually, Pletnev would not be Pletnev if it were not for this absolute completeness in everything that is the work of his hands – if not for this captivating technical skill. “In art, a graceful form is a great thing, especially where inspiration does not break through in stormy waves …” (On musical performance. – M., 1954. P. 29.)– once wrote V. G. Belinsky. He had in mind the contemporary actor V. A. Karatygin, but he expressed the universal law, which is related not only to the drama theater, but also to the concert stage. And none other than Pletnev is a magnificent confirmation of this law. He can be more or less passionate about the process of making music, he can perform more or less successfully – the only thing he simply cannot be is sloppy …

“There are concert players,” Mikhail Vasilievich continues, in whose playing one sometimes feels some kind of approximation, sketchiness. Now, you look, they thickly “smear” a technically difficult place with the pedal, then they artistically throw up their hands, roll their eyes to the ceiling, diverting the listener’s attention from the main thing, from the keyboard … Personally, this is alien to me. I repeat: I proceed from the premise that in a work performed in public, everything should be brought to full professional completeness, sharpness, and technical perfection in the course of homework. In life, in everyday life, we respect only honest people, don’t we? — and we do not respect those who lead us astray. It’s the same on stage.”

Over the years, Pletnev is more and more strict with himself. The criteria by which he is guided in his work are being made more rigid. The terms of learning new works become longer.

“You see, when I was still a student and just starting to play, my requirements for playing were based not only on my own tastes, views, professional approaches, but also on what I heard from my teachers. To a certain extent, I saw myself through the prism of their perception, I judged myself based on their instructions, assessments, and wishes. And it was completely natural. It happens to everyone when they study. Now I myself, from beginning to end, determine my attitude to what has been done. It’s more interesting, but also more difficult, more responsible.”

* * *

Pletnev today is steadily, consistently moving forward. This is noticeable to every unprejudiced observer, anyone who knows how see. And wants see, of course. At the same time, it would be wrong to think, of course, that his path is always even and straight, free from any internal zigzags.

“I can’t say in any way that I have now come to something unshakable, final, firmly established. I can’t say: before, they say, I made such and such or such mistakes, but now I know everything, I understand and I won’t repeat the mistakes again. Of course, some misconceptions and miscalculations of the past become more obvious to me over the years. However, I am far from thinking that today I do not fall into other delusions that will make themselves felt later.

Perhaps it is the unpredictability of Pletnev’s development as an artist – those surprises and surprises, difficulties and contradictions, those gains and losses that this development involves – and causes an increased interest in his art. An interest that has proven its strength and stability both in our country and abroad.

Of course, not everyone loves Pletnev equally. There is nothing more natural and understandable. The outstanding Soviet prose writer Y. Trifonov once said: “In my opinion, a writer cannot and should not be liked by everyone” (Trifonov Yu. How our word will respond … – M., 1985. S. 286.). Musician too. But practically everyone respects Mikhail Vasilyevich, not excluding the absolute majority of his colleagues on the stage. There is probably no indicator more reliable and true, if we talk about the real, and not the imaginary merits of the performer.

The respect that Pletnev enjoys is greatly facilitated by his gramophone records. By the way, he is one of those musicians who not only do not lose on recordings, but sometimes even win. An excellent confirmation of this is the discs depicting the performance by the pianist of several Mozart sonatas (“Melody”, 1985), the B minor sonata, “Mephisto-Waltz” and other pieces by Liszt (“Melody”, 1986), the First Piano Concerto and “Rhapsody on a Theme Paganini” by Rachmaninov (“Melody”, 1987). “The Seasons” by Tchaikovsky (“Melody”, 1988). This list could be continued if desired …

In addition to the main thing in his life – playing the piano, Pletnev also composes, conducts, teaches, and is engaged in other works; In a word, it takes on a lot. Now, however, he is increasingly thinking about the fact that it is impossible to constantly work only for “bestowal”. That it is necessary to slow down from time to time, look around, perceive, assimilate …

“We need some internal savings. Only when they are, there is a desire to meet with listeners, to share what you have. For a performing musician, as well as a composer, writer, painter, this is extremely important – the desire to share … To tell people what you know and feel, to convey your creative excitement, your admiration for music, your understanding of it. If there is no such desire, you are not an artist. And your art is not art. I have noticed more than once, when meeting with great musicians, that this is why they go on stage, that they need to make their creative concepts public, to tell about their attitude to this or that work, the author. I am convinced that this is the only way to treat your business.”

G. Tsypin, 1990

In 1980 Pletnev made his debut as a conductor. Giving the main forces of pianistic activity, he often appeared at the console of the leading orchestras of our country. But the rise of his conducting career came in the 90s, when Mikhail Pletnev founded the Russian National Orchestra (1990). Under his leadership, the orchestra, assembled from among the best musicians and like-minded people, very quickly gained a reputation as one of the best orchestras in the world.

Conducting activity of Mikhail Pletnev is rich and varied. Over the past seasons, the Maestro and the RNO have presented a number of monographic programs dedicated to J.S. Bach, Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Liszt, Wagner, Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Scriabin, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Stravinsky… Increasing attention to the conductor focuses on the genre of opera: in October 2007, Mikhail Pletnev made his debut as an opera conductor at the Bolshoi Theater with Tchaikovsky’s opera The Queen of Spades. In subsequent years, the conductor performed concert performances of Rachmaninov’s Aleko and Francesca da Rimini, Bizet’s Carmen (P.I. Tchaikovsky Concert Hall), and Rimsky-Korsakov’s May Night (Arkhangelskoye Estate Museum).

In addition to fruitful collaboration with the Russian National Orchestra, Mikhail Pletnev acts as a guest conductor with such leading musical groups as the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Tokyo Philharmonic…

In 2006, Mikhail Pletnev created the Mikhail Pletnev Foundation for the Support of National Culture, an organization whose goal, along with providing Pletnev’s main brainchild, the Russian National Orchestra, is to organize and support cultural projects of the highest level, such as the Volga Tours, a memorial concert in memory of the victims of the terrible tragedies in Beslan, the musical and educational program “Magic of Music”, designed specifically for pupils of orphanages and boarding schools for children with physical and mental disabilities, a subscription program in the Concert Hall “Orchestrion”, where concerts are held together with the MGAF, including for socially unprotected citizens, extensive discographic activity and the Big RNO Festival.

A very significant place in the creative activity of M. Pletnev is occupied by composition. Among his works are Triptych for Symphony Orchestra, Fantasy for Violin and Orchestra, Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra, piano arrangements of suites from the music of the ballets The Nutcracker and The Sleeping Beauty by Tchaikovsky, excerpts from the music of the ballet Anna Karenina by Shchedrin, Viola Concerto, arrangement for clarinet of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.

Mikhail Pletnev’s activities are constantly marked by high awards – he is a laureate of State and international awards, including the Grammy and Triumph awards. Only in 2007, the musician was awarded the Prize of the President of the Russian Federation, the Order of Merit for the Fatherland, III degree, the Order of Daniel of Moscow, granted by His Holiness Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow and All Russia.