Frederic Chopin |

Contents

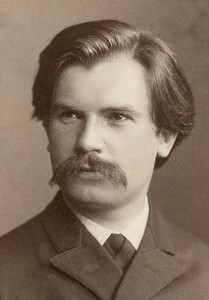

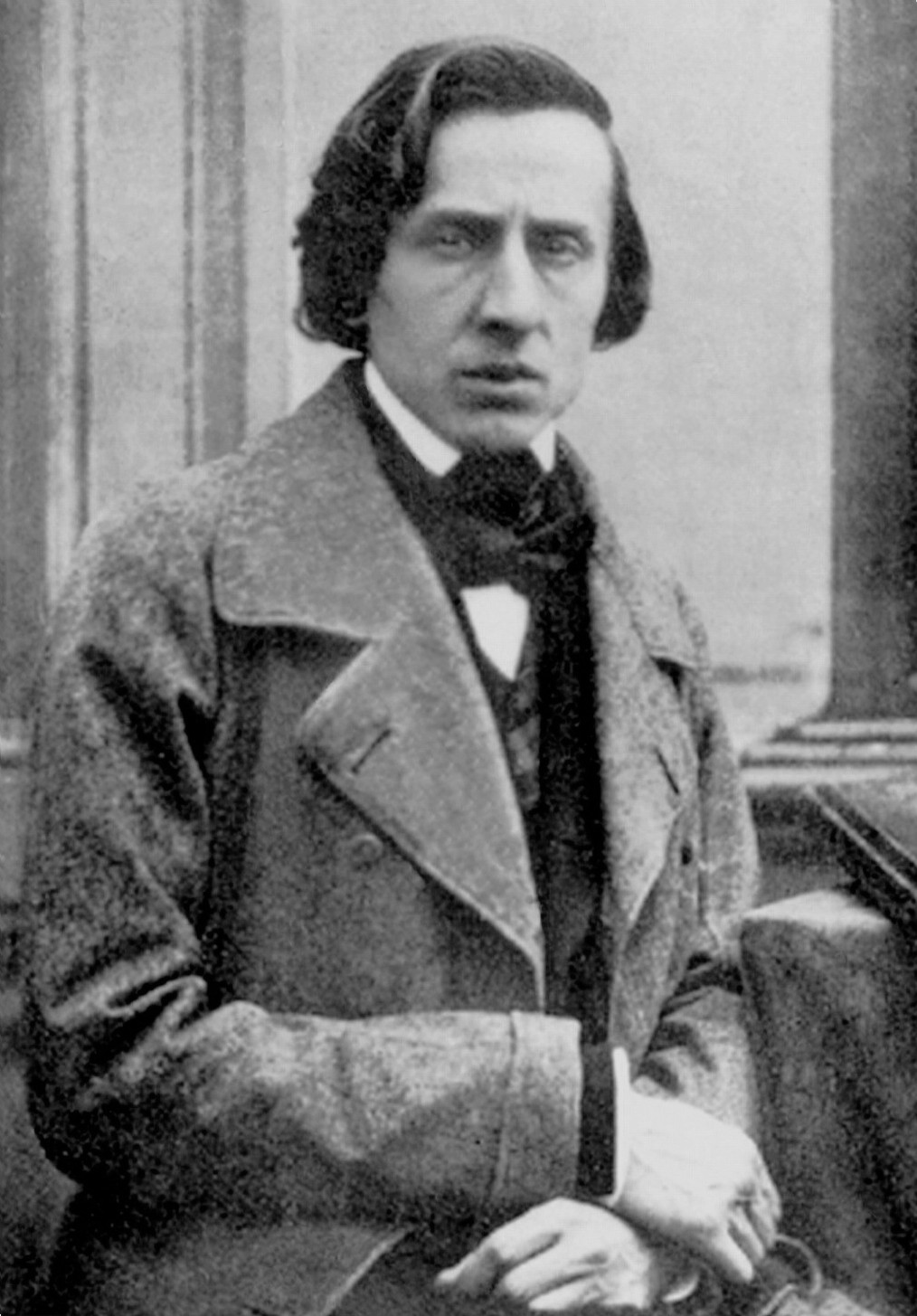

Frederic Chopin

Mysterious, devilish, feminine, courageous, incomprehensible, everyone understands the tragic Chopin. S. Richter

According to A. Rubinstein, “Chopin is a bard, rhapsodist, spirit, soul of the piano.” The most unique thing in Chopin’s music is connected with the piano: its quivering, refinement, “singing” of all texture and harmony, enveloping the melody with an iridescent airy “haze”. All the multicoloredness of the romantic worldview, everything that usually required monumental compositions (symphonies or operas) for its embodiment, was expressed by the great Polish composer and pianist in piano music (Chopin has very few works with the participation of other instruments, human voice or orchestra). Contrasts and even polar opposites of romanticism in Chopin turned into the highest harmony: fiery enthusiasm, increased emotional “temperature” – and strict logic of development, intimate confidentiality of lyrics – and conceptuality of symphonic scales, artistry, brought to aristocratic sophistication, and next to it – the primordial purity of “folk pictures.” In general, the originality of Polish folklore (its modes, melodies, rhythms) permeated the entire music of Chopin, who became the musical classic of Poland.

Chopin was born near Warsaw, in Zhelyazova Wola, where his father, a native of France, worked as a home teacher in a count’s family. Shortly after the birth of Fryderyk, the Chopin family moved to Warsaw. Phenomenal musical talent manifests itself already in early childhood, at the age of 6 the boy composes his first work (polonaise), and at 7 he performs as a pianist for the first time. Chopin receives general education at the Lyceum, he also takes piano lessons from V. Zhivny. The formation of a professional musician is completed at the Warsaw Conservatory (1826-29) under the direction of J. Elsner. Chopin’s talent was manifested not only in music: from childhood he composed poetry, played in home performances, and drew wonderfully. For the rest of his life, Chopin retained the gift of a caricaturist: he could draw or even depict someone with facial expressions in such a way that everyone unmistakably recognized this person.

The artistic life of Warsaw gave a lot of impressions to the beginning musician. Italian and Polish national opera, tours of major artists (N. Paganini, J. Hummel) inspired Chopin, opened up new horizons for him. Often during the summer holidays, Fryderyk visited his friends’ country estates, where he not only listened to the play of village musicians, but sometimes he himself played some instrument. Chopin’s first composing experiments were poeticized dances of Polish life (polonaise, mazurka), waltzes, and nocturnes – miniatures of a lyric-contemplative nature. He also turns to the genres that formed the basis of the repertoire of the then virtuoso pianists – concert variations, fantasies, rondos. The material for such works was, as a rule, themes from popular operas or folk Polish melodies. Variations on a theme from W. A. Mozart’s opera “Don Giovanni” met with a warm response from R. Schumann, who wrote an enthusiastic article about them. Schumann also owns the following words: “… If a genius like Mozart is born in our time, he will write concertos more like Chopin than Mozart.” 2 concertos (especially in E minor) were the highest achievement of Chopin’s early work, reflecting all the facets of the artistic world of the twenty-year-old composer. The elegiac lyrics, akin to the Russian romance of those years, are set off by the brilliance of virtuosity and spring-like bright folk-genre themes. Mozart’s perfect forms are imbued with the spirit of romanticism.

During a tour to Vienna and the cities of Germany, Chopin was overtaken by the news of the defeat of the Polish uprising (1830-31). The tragedy of Poland became the strongest personal tragedy, combined with the impossibility of returning to their homeland (Chopin was a friend of some participants in the liberation movement). As B. Asafiev noted, “the collisions that worried him focused on various stages of love languor and on the brightest explosion of despair in connection with the death of the fatherland.” From now on, genuine drama penetrates into his music (Ballad in G minor, Scherzo in B minor, Etude in C minor, often called “Revolutionary”). Schumann writes that “…Chopin introduced the spirit of Beethoven into the concert hall.” The ballad and the scherzo are new genres for piano music. Ballads were called detailed romances of a narrative-dramatic nature; for Chopin, these are large works of a poem type (written under the impression of the ballads of A. Mickiewicz and Polish dumas). The scherzo (usually a part of the cycle) is also being rethought – now it has begun to exist as an independent genre (not at all comic, but more often – spontaneously demonic content).

Chopin’s subsequent life is connected with Paris, where he ends up in 1831. In this seething center of artistic life, Chopin meets artists from different European countries: composers G. Berlioz, F. Liszt, N. Paganini, V. Bellini, J. Meyerbeer , pianist F. Kalkbrenner, writers G. Heine, A. Mickiewicz, George Sand, artist E. Delacroix, who painted a portrait of the composer. Paris in the 30s XIX century – one of the centers of the new, romantic art, asserted itself in the fight against academism. According to Liszt, “Chopin openly joined the ranks of the Romantics, having nevertheless written the name of Mozart on his banner.” Indeed, no matter how far Chopin went in his innovation (even Schumann and Liszt did not always understand him!), his work was in the nature of an organic development of tradition, its, as it were, magical transformation. The idols of the Polish romantic were Mozart and, in particular, J. S. Bach. Chopin was generally disapproving of contemporary music. Probably, his classically strict, refined taste, which did not allow any harshness, rudeness and extremes of expression, affected here. With all the secular sociability and friendliness, he was restrained and did not like to open his inner world. So, about music, about the content of his works, he spoke rarely and sparingly, most often disguised as some kind of joke.

In the etudes created in the first years of Parisian life, Chopin gives his understanding of virtuosity (as opposed to the art of fashionable pianists) as a means that serves to express artistic content and is inseparable from it. Chopin himself, however, rarely performed in concerts, preferring the chamber, more comfortable atmosphere of a secular salon to a large hall. Income from concerts and music publications was lacking, and Chopin was forced to give piano lessons. At the end of the 30s. Chopin completes the cycle of preludes, which have become a real encyclopedia of romanticism, reflecting the main collisions of the romantic worldview. In the preludes, the smallest pieces, a special “density”, a concentration of expression, is achieved. And again we see an example of a new attitude to the genre. In ancient music, the prelude has always been an introduction to some work. With Chopin, this is a valuable piece in itself, at the same time retaining some understatement of the aphorism and “improvisational” freedom, which is so consonant with the romantic worldview. The cycle of preludes ended on the island of Mallorca, where Chopin undertook a trip together with George Sand (1838) to improve his health. In addition, Chopin traveled from Paris to Germany (1834-1836), where he met with Mendelssohn and Schumann, and saw his parents in Carlsbad, and to England (1837).

In 1840, Chopin wrote the Second Sonata in B flat minor, one of his most tragic works. Its 3rd part – “The Funeral March” – has remained a symbol of mourning to this day. Other major works include ballads (4), scherzos (4), Fantasia in F minor, Barcarolle, Cello and Piano Sonata. But no less important for Chopin were the genres of romantic miniature; there are new nocturnes (total about 20), polonaises (16), waltzes (17), impromptu (4). The composer’s special love was the mazurka. Chopin’s 52 mazurkas, poeticizing the intonations of Polish dances (mazur, kujawiak, oberek), became a lyrical confession, the composer’s “diary”, an expression of the most intimate. It is no coincidence that the last work of the “piano poet” was the mournful F-minor mazurka op. 68, No. 4 – the image of a distant, unattainable homeland.

The culmination of Chopin’s entire work was the Third Sonata in B minor (1844), in which, as in other later works, the brilliance and color of the sound is enhanced. The terminally ill composer creates music full of light, an enthusiastic ecstatic merging with nature.

In the last years of his life, Chopin made a major tour of England and Scotland (1848), which, like the break in relations with George Sand that preceded it, finally undermined his health. Chopin’s music is absolutely unique, while it influenced many composers of subsequent generations: from F. Liszt to K. Debussy and K. Szymanowski. Russian musicians A. Rubinshtein, A. Lyadov, A. Skryabin, S. Rachmaninov had special, “kindred” feelings for her. Chopin’s art has become for us an exceptionally integral, harmonious expression of the romantic ideal and a daring, full of struggle, striving for it.

K. Zenkin

In the 30s and 40s of the XNUMXth century, world music was enriched by three major artistic phenomena that came from the east of Europe. With the creativity of Chopin, Glinka, Liszt, a new page has opened in the history of musical art.

For all their artistic originality, with a noticeable difference in the fate of their art, these three composers are united by a common historical mission. They were the initiators of that movement for the creation of national schools, which forms the most important aspect of the pan-European musical culture of the second half of the 30th (and the beginning of the XNUMXth) century. During the two and a half centuries that followed the Renaissance, world-class musical creativity developed almost exclusively around three national centers. All any significant artistic currents that flowed into the mainstream of pan-European music came from Italy, France and the Austro-German principalities. Until the middle of the XNUMXth century, hegemony in the development of world music belonged undividedly to them. And suddenly, starting from the XNUMXs, on the “periphery” of Central Europe, one after another, large art schools appeared, belonging to those national cultures that until now either did not enter the “high road” of the development of musical art at all, or left it long ago. and remained in the shadows for a long time.

These new national schools – first of all Russian (which soon took if not the first, then one of the first places in world musical art), Polish, Czech, Hungarian, then Norwegian, Spanish, Finnish, English and others – were called upon to pour a fresh stream into ancient traditions of European music. They opened up new artistic horizons for her, renewed and immensely enriched her expressive resources. The picture of pan-European music in the second half of the XNUMXth century is inconceivable without new, rapidly flourishing national schools.

The founders of this movement were the three above-named composers who entered the world stage at the same time. Outlining new paths in the pan-European professional art, these artists acted as representatives of their national cultures, revealing hitherto unknown enormous values accumulated by their peoples. Art on such a scale as the work of Chopin, Glinka or Liszt could form only on prepared national soil, mature as the fruit of an ancient and developed spiritual culture, its own traditions of musical professionalism, which has not exhausted itself, and continuously born folklore. Against the backdrop of the prevailing norms of professional music in Western Europe, the bright originality of the still “untouched” folklore of the countries of Eastern Europe in itself made an enormous artistic impression. But the connections of Chopin, Glinka, Liszt with the culture of their country, of course, did not end there. The ideals, aspirations and sufferings of their people, their dominant psychological makeup, the historically established forms of their artistic life and way of life – all this, no less than reliance on musical folklore, determined the features of the creative style of these artists. The music of Fryderyk Chopin was such an embodiment of the spirit of the Polish people. Despite the fact that the composer spent most of his creative life outside his homeland, nevertheless, it was he who was destined to play the role of the main, generally recognized representative of the culture of his country in the eyes of the whole world until our time. This composer, whose music has entered the daily spiritual life of every cultured person, is perceived primarily as the son of the Polish people.

Chopin’s music immediately received universal recognition. Leading romantic composers, leading the struggle for a new art, felt in him a like-minded person. His work was naturally and organically included in the framework of the advanced artistic searches of his generation. (Let us recall not only Schumann’s critical articles, but also his “Carnival”, where Chopin appears as one of the “Davidsbündlers”.) The new lyrical theme of his art, characteristic of her now romantic-dreamy, now explosively dramatic refraction, striking the boldness of the musical (and especially harmonic) language, innovation in the field of genres and forms – all this echoed the searches of Schumann, Berlioz, Liszt, Mendelssohn. And at the same time, Chopin’s art was characterized by an endearing originality that distinguished him from all his contemporaries. Of course, Chopin’s originality came from the national-Polish origins of his work, which his contemporaries immediately felt. But no matter how great the role of Slavic culture in the formation of Chopin’s style, it is not only this that he owes to his truly amazing originality, Chopin, like no other composer, managed to combine and fuse together artistic phenomena that at first glance seem to be mutually exclusive. One could speak of the contradictions of Chopin’s creativity if it were not soldered together by an amazingly integral, individual, extremely convincing style, based on the most diverse, sometimes even extreme currents.

So, of course, the most characteristic feature of Chopin’s work is its enormous, immediate accessibility. Is it easy to find another composer whose music could rival Chopin’s in its instantaneous and deeply penetrating power of influence? Millions of people came to professional music “through Chopin”, many others who are indifferent to musical creativity in general, nevertheless perceive Chopin’s “word” with keen emotionality. Only individual works by other composers – for example, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony or Pathétique Sonata, Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony or Schubert’s “Unfinished” – can bear comparison with the enormous immediate charm of each Chopin bar. Even during the composer’s lifetime, his music did not have to fight its way to the audience, overcome the psychological resistance of a conservative listener – a fate that all the brave innovators among nineteenth-century Western European composers shared. In this sense, Chopin is closer to the composers of the new national-democratic schools (established mainly in the second half of the century) than to contemporary Western European romantics.

Meanwhile, his work is at the same time striking in its independence from the traditions that have developed in the national democratic schools of the XNUMXth century. It is precisely those genres that played the main and supporting role for all other representatives of national-democratic schools – opera, everyday romance and program symphonic music – are either completely absent from Chopin’s heritage or occupy a secondary place in it.

The dream of creating a national opera, which inspired other Polish composers – Chopin’s predecessors and contemporaries – did not materialize in his art. Chopin was not interested in musical theater. Symphonic music in general, and program music in particular, did not enter into it at all. range of his artistic interests. The songs created by Chopin are of a certain interest, but they occupy a purely secondary position in comparison with all his works. His music is alien to the “objective” simplicity, “ethnographic” brightness of style, characteristic of the art of national-democratic schools. Even in mazurkas, Chopin stands apart from Moniuszko, Smetana, Dvorak, Glinka and other composers who also worked in the genre of folk or everyday dance. And in the mazurkas, his music is saturated with that nervous artistry, that spiritual refinement that distinguishes every thought he expresses.

Chopin’s music is the quintessence of refinement in the best sense of the word, elegance, finely polished beauty. But can it be denied that this art, which outwardly belongs to an aristocratic salon, subjugates the feelings of the masses of many thousands and carries them along with no less force than is given to a great orator or popular tribune?

The “salonness” of Chopin’s music is its other side, which seems to be in sharp contradiction with the general creative image of the composer. Chopin’s connections with the salon are indisputable and obvious. It is no coincidence that in the XNUMXth century that narrow salon interpretation of Chopin’s music was born, which, in the form of provincial survivals, was preserved in some places in the West even in the XNUMXth century. As a performer, Chopin did not like and was afraid of the concert stage, in life he moved mainly in an aristocratic environment, and the refined atmosphere of the secular salon invariably inspired and inspired him. Where, if not in a secular salon, should one look for the origins of the inimitable refinement of Chopin’s style? The brilliance and “luxurious” beauty of virtuosity characteristic of his music, in the complete absence of flashy acting effects, also originated not just in a chamber setting, but in a chosen aristocratic environment.

But at the same time, Chopin’s work is the complete antipode of salonism. Superficiality of feelings, false, not genuine virtuosity, posturing, emphasis on the elegance of form at the expense of depth and content – these obligatory attributes of secular salonism are absolutely alien to Chopin. Despite the elegance and refinement of the forms of expression, Chopin’s statements are always imbued with such seriousness, saturated with such tremendous power of thought and feeling that they simply do not excite, but often shock the listener. The psychological and emotional impact of his music is so great that in the West he was even compared with Russian writers – Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Tolstoy, believing that along with them he revealed the depths of the “Slavic soul”.

Let us note one more seeming contradiction characteristic of Chopin. An artist of genius talent, who left a deep mark on the development of world music, reflecting in his work a wide range of new ideas, found it possible to express himself completely by means of pianistic literature alone. No other composer, either of Chopin’s predecessors or followers, limited himself entirely, like him, to the framework of piano music (works created by Chopin not for the piano occupy such an insignificant place in his creative heritage that they do not change the picture as a whole) .

No matter how great the innovative role of the piano in Western European music of the XNUMXth century, no matter how great the tribute paid to it by all the leading Western European composers starting with Beethoven, none of them, including even the greatest pianist of his century, Franz Liszt, was not completely satisfied with its expressive possibilities. At first glance, Chopin’s exclusive commitment to piano music may give the impression of being narrow-minded. But in fact, it was by no means the poverty of ideas that allowed him to be satisfied with the capabilities of one instrument. Having ingeniously comprehended all the expressive resources of the piano, Chopin was able to infinitely expand the artistic boundaries of this instrument and give it an all-encompassing significance that has never been seen before.

Chopin’s discoveries in the field of piano literature were not inferior to the achievements of his contemporaries in the field of symphonic or operatic music. If the virtuoso traditions of pop pianism prevented Weber from finding a new creative style, which he found only in musical theater; if Beethoven’s piano sonatas, for all their enormous artistic significance, were approaches to even higher creative heights of the brilliant symphonist; if Liszt, having reached creative maturity, almost abandoned composing for the piano, devoting himself mainly to symphonic work; even if Schumann, who showed himself most fully as a piano composer, paid tribute to this instrument for only one decade, then for Chopin, piano music was everything. It was both the composer’s creative laboratory and the area in which his highest generalizing achievements were manifested. It was both a form of affirmation of a new virtuoso technique and a sphere of expression of the deepest intimate moods. Here, with remarkable fullness and amazing creative imagination, both the “sensual” colorful and coloristic side of the sounds and the logic of a large-scale musical form were realized with an equal degree of perfection. Moreover, some of the problems posed by the entire course of the development of European music in the XNUMXth century, Chopin resolved in his piano works with greater artistic persuasiveness, at a higher level than was achieved by other composers in the field of symphonic genres.

The seeming inconsistency can also be seen when discussing the “main theme” of Chopin’s work.

Who was Chopin – a national and folk artist, glorifying the history, life, art of his country and his people, or a romantic, immersed in intimate experiences and perceiving the whole world in a lyrical refraction? And these two extreme sides of the musical aesthetics of the XNUMXth century were combined with him in a harmonious balance.

Of course, the main creative theme of Chopin was the theme of his homeland. The image of Poland – pictures of its majestic past, images of national literature, modern Polish life, the sounds of folk dances and songs – all this passes through Chopin’s work in an endless string, forming its main content. With an inexhaustible imagination, Chopin could vary this one theme, without which his work would immediately lose all its individuality, richness and artistic power. In a certain sense, he could even be called an artist of a “monothematic” warehouse. It is not surprising that Schumann, as a sensitive musician, immediately appreciated the revolutionary patriotic content of Chopin’s work, calling his works “guns hidden in flowers.”

“… If a powerful autocratic monarch there, in the North, knew what a dangerous enemy lies for him in the works of Chopin, in the simple tunes of his mazurkas, he would have banned music …” – the German composer wrote.

And, however, in the whole appearance of this “folk singer”, in the manner with which he sang of the greatness of his country, there is something deeply akin to the aesthetics of contemporary Western romantic lyricists. Chopin’s thought and thoughts about Poland were clothed in the form of “an unattainable romantic dream”. The difficult (and in the eyes of Chopin and his contemporaries almost hopeless) fate of Poland gave his feeling for his homeland both the character of a painful yearning for an unattainable ideal and a shade of enthusiastically exaggerated admiration for its beautiful past. For Western European romantics, the protest against the gray everyday life, against the real world of “philistines and merchants” was expressed in longing for the non-existent world of beautiful fantasy (for the “blue flower” of the German poet Novalis, for “unearthly light, unseen by anyone on land or at sea” by the English romantic Wordsworth, according to the magical realm of Oberon in Weber and Mendelssohn, according to the fantastic ghost of an inaccessible beloved in Berlioz, etc.). For Chopin, the “beautiful dream” throughout his life was the dream of a free Poland. In his work there are no frankly enchanting, otherworldly, fairy-tale-fantastic motifs, so characteristic of Western European romantics in general. Even the images of his ballads, inspired by the romantic ballads of Mickiewicz, are devoid of any clearly perceptible fairy tale flavor.

Chopin’s images of longing for the indefinite world of beauty manifested themselves not in the form of an attraction to the ghostly world of dreams, but in the form of an unquenchable homesickness.

The fact that from the age of twenty Chopin was forced to live in a foreign land, that for almost twenty subsequent years his foot never set foot on Polish soil, inevitably strengthened his romantic and dreamy attitude to everything connected with the homeland. In his view, Poland became more and more like a beautiful ideal, devoid of the rough features of reality and perceived through the prism of lyrical experiences. Even the “genre pictures” that are found in his mazurkas, or almost programmatic images of artistic processions in polonaises, or the broad dramatic canvases of his ballads, inspired by the epic poems of Mickiewicz – all of them, to the same extent as purely psychological sketches, are interpreted by Chopin outside the objective “tangibility”. These are idealized memories or rapturous dreams, these are elegiac sadness or passionate protests, these are fleeting visions or flashed faith. That is why Chopin, despite the obvious connections of his work with the genre, everyday, folk music of Poland, with its national literature and history, is nevertheless perceived not as a composer of an objective genre, epic or theatrical-dramatic warehouse, but as a lyricist and dreamer. That is why the patriotic and revolutionary motifs that form the main content of his work were not embodied either in the opera genre, associated with the objective realism of the theater, or in the song, based on soil household traditions. It was precisely piano music that ideally corresponded to the psychological warehouse of Chopin’s thinking, in which he himself discovered and developed enormous opportunities for expressing images of dreams and lyrical moods.

No other composer, up to our time, has surpassed the poetic charm of Chopin’s music. With all the variety of moods – from the melancholy of “moonlight” to the explosive drama of passions or chivalrous heroics – Chopin’s statements are always imbued with high poetry. Perhaps it is precisely the amazing combination of the folk foundations of Chopin’s music, its national soil and revolutionary moods with incomparable poetic inspiration and exquisite beauty that explains its enormous popularity. To this day, she is perceived as the embodiment of the spirit of poetry in music.

* * *

Chopin’s influence on subsequent musical creativity is great and versatile. It affects not only the sphere of pianism, but also in the field of musical language (the tendency to emancipate harmony from the laws of diatonicity), and in the field of musical form (Chopin, in essence, was the first in instrumental music to create a free form of romantics), and finally – in aesthetics. The fusion of the national-soil principle achieved by him with the highest level of modern professionalism can still serve as a criterion for composers of national-democratic schools.

Chopin’s closeness to the paths developed by Russian composers of the 1894th century was manifested in the high appreciation of his work, which was expressed by outstanding representatives of the musical thought of Russia (Glinka, Serov, Stasov, Balakirev). Balakirev took the initiative to open a monument to Chopin in Zhelyazova Vola in XNUMX. An outstanding interpreter of Chopin’s music was Anton Rubinstein.

V. Konen

Compositions:

for piano and orchestra:

concerts — No. 1 e-moll op. 11 (1830) and no. 2 f-moll op. 21 (1829), variations on a theme from Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni op. 2 (“Give me your hand, beauty” – “La ci darem la mano”, 1827), rondo-krakowiak F-dur op. 14, Fantasy on Polish Themes A-dur op. 13 (1829), Andante spianato and polonaise Es-dur op. 22 (1830-32);

chamber instrumental ensembles:

sonata for piano and cello g-moll op. 65 (1846), variations for flute and piano on a theme from Rossini’s Cinderella (1830?), introduction and polonaise for piano and cello C-dur op. 3 (1829), Large concert duet for piano and cello on a theme from Meyerbeer’s Robert the Devil, with O. Franchomme (1832?), piano trio g-moll op. 8 (1828);

for piano:

sonatas c minor op. 4 (1828), b-moll op. 35 (1839), b-moll op. 58 (1844), concert Allegro A-dur op. 46 (1840-41), fantasy in f minor op. 49 (1841), 4 ballads – G minor op. 23 (1831-35), F major op. 38 (1839), A major op. 47 (1841), in F minor op. 52 (1842), 4 scherzo – B minor op. 20 (1832), B minor op. 31 (1837), C sharp minor op. 39 (1839), E major op. 54 (1842), 4 impromptu — As-dur op. 29 (1837), Fis-dur op. 36 (1839), Ges-dur op. 51 (1842), fantasy-impromptu cis-moll op. 66 (1834), 21 nocturnes (1827-46) – 3 op. 9 (B minor, E flat major, B major), 3 op. 15 (F major, F major, G minor), 2 op. 27 (C sharp minor, D major), 2 op. 32 (H major, A flat major), 2 op. 37 (G minor, G major), 2 op. 48 (C minor, F sharp minor), 2 op. 55 (F minor, E flat major), 2 op.62 (H major, E major), op. 72 in E minor (1827), C minor without op. (1827), C sharp minor (1837), 4 rondo – C minor op. 1 (1825), F major (mazurki style) Or. 5 (1826), E flat major op. 16 (1832), C major op. mail 73 (1840), 27 studies – 12 op. 10 (1828-33), 12 op. 25 (1834-37), 3 “new” (F minor, A major, D major, 1839); foreplay – 24 op. 28 (1839), C sharp minor op. 45 (1841); waltzes (1827-47) — A flat major, E flat major (1827), E flat major op. 18, 3 op. 34 (A flat major, A minor, F major), A flat major op. 42, 3 op. 64 (D major, C sharp minor, A flat major), 2 op. 69 (A flat major, B minor), 3 op. 70 (G major, F minor, D major), E major (approx. 1829), A minor (con. 1820-х гг.), E minor (1830); Mazurkas – 4 op. 6 (F sharp minor, C sharp minor, E major, E flat minor), 5 op. 7 (B major, A minor, F minor, A major, C major), 4 op. 17 (B major, E minor, A major, A minor), 4 op. 24 (G minor, C major, A major, B minor), 4 op. 30 (C minor, B minor, D major, C sharp minor), 4 op. 33 (G minor, D major, C major, B minor), 4 op. 41 (C sharp minor, E minor, B major, A flat major), 3 op. 50 (G major, A flat major, C sharp minor), 3 op. 56 (B major, C major, C minor), 3 op. 59 (A minor, A major, F sharp minor), 3 op. 63 (B major, F minor, C sharp minor), 4 op. 67 (G major and C major, 1835; G minor, 1845; A minor, 1846), 4 op. 68 (C major, A minor, F major, F minor), polonaises (1817-1846) — g-major, B-major, As-major, gis-minor, Ges-major, b-minor, 2 op. 26 (cis-small, es-small), 2 op. 40 (A-major, c-minor), fifth-minor op. 44, As-dur op. 53, As-dur (pure-muscular) op. 61, 3 op. 71 (d-minor, B-major, f-minor), flute As-major op. 43 (1841), 2 counter dances (B-dur, Ges-dur, 1827), 3 ecossaises (D major, G major and Des major, 1830), Bolero C major op. 19 (1833); for piano 4 hands – variations in D-dur (on a theme by Moore, not preserved), F-dur (both cycles of 1826); for two pianos — Rondo in C major op. 73 (1828); 19 songs for voice and piano – op. 74 (1827-47, to verses by S. Witvitsky, A. Mickiewicz, Yu. B. Zalesky, Z. Krasiński and others), variations (1822-37) – on the theme of the German song E-dur (1827), Reminiscence of Paganini (on the theme of the Neapolitan song “Carnival in Venice”, A-dur, 1829), on the theme from Herold’s opera “Louis” (B-dur op. 12, 1833), on the theme of the March of the Puritans from Bellini’s opera Le Puritani, Es-dur (1837), barcarolle Fis-dur op. 60 (1846), Cantabile B-dur (1834), Album Leaf (E-dur, 1843), lullaby Des-dur op. 57 (1843), Largo Es-dur (1832?), Funeral March (c-moll op. 72, 1829).