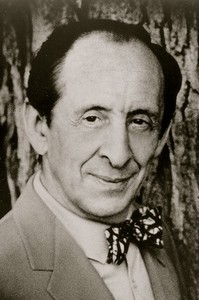

Evgeny Igorevich Kissin |

Evgeny Kissin

The general public first learned about Evgeny Kisin in 1984, when he played with an orchestra conducted by Dm. Kitayenko two piano concertos by Chopin. This event took place in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory and created a real sensation. The thirteen-year-old pianist, a sixth-grade student of the Gnessin Secondary Special Music School, was immediately spoken of as a miracle. Moreover, not only gullible and inexperienced music lovers spoke, but also professionals. Indeed, what this boy did at the piano was very much like a miracle …

Zhenya was born in 1971, in Moscow, in a family that can be said to be half musical. (His mother is a music school teacher in the piano class; his older sister, also a pianist, once studied at the Central Music School at the Conservatory.) At first, it was decided to release him from music lessons – enough, they say, one child did not have a normal childhood, let him be at least the second one. The boy’s father is an engineer, why shouldn’t he, in the end, follow the same path? … However, it happened differently. Even as a baby, Zhenya could listen to his sister’s game for hours without stopping. Then he began to sing – precisely and clearly – everything that came to his ear, whether it was Bach’s fugues or Beethoven’s Rondo “Fury over a Lost Penny.” At the age of three, he began to improvise something, picking up the melodies he liked on the piano. In a word, it became absolutely clear that it was impossible not to teach him music. And that he was not destined to be an engineer.

The boy was about six years old when he was brought to A.P. Kantor, a well-known among Muscovites teacher of the Gnessin school. “From our very first meeting, he began to surprise me,” recalls Anna Pavlovna, “to surprise me continuously, at every lesson. To tell the truth, he sometimes does not cease to amaze me even today, although so many years have passed since the day we met. How he improvised at the keyboard! I can’t tell you about it, I had to hear it … I still remember how he freely and naturally “walked” through the most diverse keys (and this without knowing any theory, any rules!), And in the end he would certainly return to the tonic. And everything came out of him so harmoniously, logically, beautifully! Music was born in his head and under his fingers, always momentarily; one motive was immediately replaced by another. No matter how much I asked him to repeat what he had just played, he refused. “But I don’t remember…” And immediately he began to fantasize something completely new.

I have had many students in my forty years of teaching. Lots of. Including truly talented ones, such as, for example, N. Demidenko or A. Batagov (now they are well-known pianists, winners of competitions). But I have never met anything like Zhenya Kisin before. It’s not that he has a great ear for music; after all, it’s not that uncommon. The main thing is how actively this rumor manifests itself! How much fantasy, creative fiction, imagination the boy has!

… The question immediately arose before me: how to teach it? Improvisation, selection by ear – all this is wonderful. But you also need knowledge of musical literacy, and what we call the professional organization of the game. It is necessary to possess some purely performing skills and abilities – and to possess them as well as possible … I must say that I do not tolerate amateurism and slovenliness in my class; for me, pianism has its own aesthetics, and it is dear to me.

In a word, I did not want to, and could not, give up at least something on the professional foundations of education. But it was also impossible to “dry” the classes … “

It must be admitted that A.P. Kantor really faced very difficult problems. Everyone who has had to deal with music pedagogy knows: the more talented the student, the more difficult (and not easier, as naively believed) the teacher. The more flexibility and ingenuity you have to show in the classroom. This is under ordinary conditions, with students of more or less ordinary giftedness. And here? How to build lessons such a child? What work style should you follow? How to communicate? What is the pace of learning? On what basis is the repertoire selected? Scales, special exercises, etc. – how to deal with them? All these questions of A.P. Kantor, despite her many years of teaching experience, had to be solved virtually anew. There were no precedents in this case. Pedagogy had never been to such a degree for her. creativitylike this time.

“To my great joy, Zhenya mastered all the “technology” of piano playing instantly. Musical notation, metro-rhythmic organization of music, basic pianistic skills and abilities – all this was given to him without the slightest difficulty. As if he already knew it once and now only remembered. I learned to read music very quickly. And then he went ahead – and at what pace!

At the end of the first year of study, Kissin played almost the entire “Children’s Album” by Tchaikovsky, Haydn’s light sonatas, Bach’s three-part inventions. In the third grade, his programs included Bach’s three- and four-voice fugues, Mozart’s sonatas, Chopin’s mazurkas; a year later – Bach’s E-minor toccata, Moszkowski’s etudes, Beethoven’s sonatas, Chopin’s F-minor piano concerto… They say that a child prodigy is always advance opportunities inherent in the age of the child; it is “running ahead” in this or that kind of activity. Zhenya Kissin, who was a classic example of a child prodigy, every year more and more noticeably and swiftly left his peers. And not only in terms of the technical complexity of the works performed. He overtook his peers in the depth of penetration into music, into its figurative and poetic structure, its essence. This, however, will be discussed later.

He was already known in Moscow musical circles. Somehow, when he was a fifth grade student, it was decided to arrange his solo concert – both useful for the boy and interesting for others. It is difficult to say how this became known outside the Gnessin school – apart from a single, small, handwritten poster, there were no other notifications about the upcoming event. Nevertheless, by the beginning of the evening, the Gnessin school was filled to overflowing with people. People crowded in the corridors, stood in a dense wall in the aisles, climbed onto tables and chairs, crowded on the windowsills … In the first part, Kissin played Bach-Marcello’s Concerto in D minor, Mendelssohn’s Prelude and Fugue, Schumann’s Variations “Abegg”, several Chopin’s mazurkas, “Dedication » Schumann-List. Chopin’s Concerto in F minor was performed in the second part. (Anna Pavlovna recalls that during the intermission Zhenya continually overcame her with the question: “Well, when will the second part begin! Well, when will the bell ring!” – he experienced such pleasure while on stage, he played so easily and well. )

The success of the evening was huge. And after a while, that same joint performance with D. Kitaenko in the BZK (two piano concertos by Chopin), which was already mentioned above, followed. Zhenya Kissin became a celebrity…

How did he impress the metropolitan audience? Some part of it – by the very fact of the performance of complex, clearly “non-childish” works. This thin, fragile teenager, almost a child, who already touched by his mere appearance on the stage – with inspiration thrown back his head, wide-open eyes, detachment from everything worldly … – everything turned out so deftly, so smoothly on the keyboard that it was simply impossible not to admire. With the most difficult and pianistically “insidious” episodes, he coped freely, without visible effort – effortlessly in the literal and figurative sense of the word.

However, experts paid attention not only, and not so much even to this. They were surprised to see that the boy was “given” to penetrate into the most reserved areas and secret places of music, into its holy of holies; we saw that this schoolboy is able to feel – and convey in his performance – the most important thing in music: its artistic sense, her expressive essence… When Kissin played Chopin’s concertos with the Kitayenko orchestra, it was as if himself Chopin, alive and authentic to his smallest features, is Chopin, and not something more or less like him, as is often the case. And this was all the more striking because at the age of thirteen to understand such phenomena in art seem to be clearly early … There is a term in science – “anticipation”, meaning anticipation, prediction by a person of something that is absent in his personal life experience (“A true poet, Goethe believed, has an innate knowledge of life, and to depict it he does not need much experience or empirical equipment …” (Eckerman I.P. Conversations with Goethe in the last years of his life. – M., 1981. S. 112).). Kissin almost from the very beginning knew, felt in music something that, given his age, he was definitely “not supposed to” know and feel. There was something strange, wonderful about it; some of the listeners, having visited the performances of the young pianist, admitted that they sometimes even felt somehow uncomfortable …

And, most remarkable, comprehended the music – in the main without anyone’s help or guidance. No doubt, his teacher, A.P. Kantor, is an outstanding specialist; and her merits in this case cannot be overestimated: she managed to become not only a skilled mentor to Zhenya, but also a good friend and adviser. However, what made his game unique in the true sense of the word, even she could not tell. Not her, not anyone else. Just his amazing intuition.

… The sensational performance at the BZK was followed by a number of others. In May of the same 1984, Kissin played a solo concert in the Small Hall of the Conservatory; the program included, in particular, Chopin’s F-minor fantasy. Let us recall in this connection that fantasy is one of the most difficult works in the repertoire of pianists. And not only in terms of virtuoso-technical – it goes without saying; the composition is difficult due to its artistic imagery, a complex system of poetic ideas, emotional contrasts, and sharply conflicted dramaturgy. Kissin performed Chopin’s fantasy with the same persuasiveness as he performed everything else. It is interesting to note that he learned this work in a surprisingly short time: only three weeks passed from the beginning of work on it to the premiere in the concert hall. Probably, one has to be a practicing musician, artist or teacher in order to properly appreciate this fact.

Those who remember the beginning of Kissin’s stage activity will apparently agree that the freshness and fullness of feelings bribed him most of all. I was fascinated by that sincerity of musical experience, that chaste purity and naivety, which are found (and even then infrequently) among very young artists. Each piece of music was performed by Kissin as if it were the most dear and beloved for him – most likely, it really was like that … All this set him apart on the professional concert stage, distinguishing his interpretations from the usual, ubiquitous performing samples: outwardly correct, “correct”, technically sound. Next to Kissin, many pianists, not excluding very authoritative ones, suddenly began to seem boring, insipid, emotionally colorless – as if secondary in their art … What he really knew how, unlike them, was to remove the scab of stamps from well-known sound canvases; and these canvases began to glow with dazzlingly bright, piercingly pure musical colors. Works long familiar to listeners became almost unfamiliar; what was heard a thousand times became new, as if it had not been heard before …

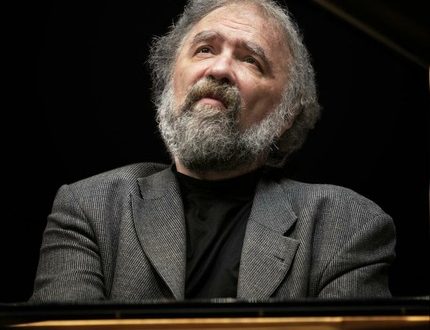

Such was Kissin in the mid-eighties, such is he, in principle, today. Although, of course, in recent years he has noticeably changed, matured. Now this is no longer a boy, but a young man in his prime, on the verge of maturity.

Being always and in everything extremely expressive, Kissin at the same time is nobly reserved for the instrument. Never crosses the boundaries of measure and taste. It is difficult to say where are the results of Anna Pavlovna’s pedagogical efforts, and where are the manifestations of his own infallible artistic instinct. Be that as it may, the fact remains: he is well brought up. Expressiveness – expressiveness, enthusiasm – enthusiasm, but the expression of the game nowhere crosses the boundaries for him, beyond which the performing “movement” could begin … It is curious: fate seems to have taken care of shading this feature of his stage appearance. Together with him, for some time, another surprisingly bright natural talent was on the concert stage – the young Polina Osetinskaya. Like Kissin, she was also in the center of attention of specialists and the general public; they talked a lot about her and him, comparing them in some way, drawing parallels and analogies. Then conversations of this kind somehow stopped by themselves, dried up. It has been confirmed (for the umpteenth time!) that recognition in professional circles requires, and with all categoricalness, observance of the rules of good taste in art. It requires the ability to beautifully, dignifiedly, correctly behave on the stage. Kissin was impeccable in this respect. That is why he remained out of competition among his peers.

He withstood another test, no less difficult and responsible. He never gave a reason to reproach himself for self-display, for excessive attention to his own person, which young talents so often sin. Moreover, they are favorites of the general public … “When you climb the stairs of art, do not knock with your heels,” the remarkable Soviet actress O. Androvskaya once wittily remarked. Kissin’s “knock of heels” was never heard. For he plays “not himself”, but the Author. Again, this would not be particularly surprising if it were not for his age.

… Kissin began his stage career, as they said, with Chopin. And not by chance, of course. He has a gift for romance; it’s more than obvious. One can recall, for example, Chopin’s mazurkas performed by him – they are tender, fragrant and fragrant like fresh flowers. The works of Schumann (Arabesques, C major fantasy, Symphonic etudes), Liszt (rhapsodies, etudes, etc.), Schubert (sonata in C minor) are close to Kissin to the same extent. Everything he does at the piano, interpreting the romantics, usually looks natural, like inhaling and exhaling.

However, A.P. Kantor is convinced that Kissin’s role is, in principle, wider and more multifaceted. In confirmation, she allows him to try himself in the most diverse layers of the pianistic repertoire. He played many works by Mozart, in recent years he often performed the music of Shostakovich (First Piano Concerto), Prokofiev (Third Piano Concerto, Sixth Sonata, “Fleeting”, separate numbers from the suite “Romeo and Juliet”). The Russian classics have firmly established themselves in his programs – Rachmaninov (Second Piano Concerto, preludes, etudes-pictures), Scriabin (Third Sonata, preludes, etudes, the plays “Fragility”, “Inspired Poem”, “Dance of Longing”). And here, in this repertoire, Kisin remains Kisin – tell the Truth and nothing but the Truth. And here it conveys not only the letter, but the very spirit of music. However, one cannot notice that not so few pianists now “cope” with the works of Rachmaninov or Prokofiev; in any case, the high-class performance of these works is not too rare. Another thing is Schumann or Chopin… “Chopinists” these days can literally be counted on the fingers. And the more often the composer’s music sounds in concert halls, the more it catches the eye. It is possible that this is precisely why Kissin evokes such sympathy from the public, and his programs from the works of romantics are met with such enthusiasm.

From the mid-eighties, Kissin began to travel abroad. To date, he has already visited, and more than once, in England, Italy, Spain, Austria, Japan, and a number of other countries. He was recognized and loved abroad; invitations to come on tour are now coming to him in ever-increasing numbers; probably, he would have agreed more often if not for his studies.

Abroad, and at home, Kissin often gives concerts with V. Spivakov and his orchestra. Spivakov, we must give him his due, generally takes an ardent part in the fate of the boy; he did and continues to do a lot for him personally, for his professional career.

During one of the tours, in August 1988, in Salzburg, Kissin was introduced to Herbert Karajan. They say that the eighty-year-old maestro could not hold back his tears when he first heard the young man play. He immediately invited him to speak together. Indeed, a few months later, on December 30 of the same year, Kissin and Herbert Karaja played Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto in West Berlin. Television broadcast this performance throughout Germany. The next evening, on New Year’s Eve, the performance was repeated; This time the broadcast went to most European countries and the USA. A few months later, the concert was performed by Kissin and Karayan on Central Television.

* * *

Valery Bryusov once said: “… Poetic talent gives a lot when it is combined with good taste and directed by a strong thought. In order for artistic creativity to win great victories, broad mental horizons are necessary for it. Only the culture of the mind makes the culture of the spirit possible.” (Russian writers about literary work. – L., 1956. S. 332.).

Kissin not only feels strongly and vividly in art; one senses both an inquisitive intellect and a broadly ramified spiritual endowment – “intelligence”, according to the terminology of Western psychologists. He loves books, knows poetry well; relatives testify that he can read whole pages by heart from Pushkin, Lermontov, Blok, Mayakovsky. Studying at school was always given to him without much difficulty, although at times he had to take hefty breaks in his studies. He has a hobby – chess.

It is difficult for outsiders to communicate with him. He is laconic – “silent”, as Anna Pavlovna says. However, in this “silent man”, apparently, there is a constant, incessant, intense and very complex inner work. The best confirmation of this is his game.

It’s hard to even imagine how difficult it will be for Kissin in the future. After all, the “application” made by him – and which! – must be justified. As well as the hopes of the public, which so warmly received the young musician, believed in him. From no one, probably, they expect so much today as from Kisin. It is impossible for him to remain the way he was two or three years ago – or even at the current level. Yes, it’s practically impossible. Here “either – or” … It means that he has no other way but to go forward, constantly multiplying himself, with each new season, new program.

Moreover, by the way, Kissin has problems that need to be addressed. There is something to work on, something to “multiply”. No matter how many enthusiastic feelings his game evokes, having looked at it more attentively and more carefully, you begin to distinguish some shortcomings, shortcomings, bottlenecks. For example, Kissin is by no means an impeccable controller of his own performance: on the stage, he sometimes involuntarily speeds up the pace, “drives up”, as they say in such cases; his piano sometimes sounds booming, viscous, “overloaded”; the musical fabric is sometimes covered with thick, abundantly overlapping pedal spots. Recently, for example, in the 1988/89 season, he played a program in the Great Hall of the Conservatory, where, along with other things, there was Chopin’s B minor sonata. Justice demands to say that the defects mentioned above were quite obvious in it.

The same concert program, by the way, included Schumann’s Arabesques. They were the first number, opened the evening and, frankly, they did not turn out too well either. “Arabesques” showed that Kissin does not immediately, not from the first minutes of the performance “enter” the music – he needs a certain time in order to emotionally warm up, to find the desired stage state. Of course, there is nothing more common, more common in mass performing practice. This happens to almost everyone. But still… Almost, but not with everyone. That is why it is impossible not to point out this Achilles heel of the young pianist.

One more thing. Perhaps the most significant. It has already been noted earlier: for Kissin there are no insurmountable virtuoso-technical barriers, he copes with any pianistic difficulties without visible effort. This, however, does not mean that he can feel any calm and carefree in terms of “technique”. Firstly, as mentioned earlier, her (“technique”) never happens to anyone. in excess, it can only be lacking. And indeed, there is a constant lack of large and demanding artists; moreover, the more significant, bolder their creative ideas, the more they lack. But it’s not just that. It must be said directly, Kisin’s pianism on its own does not yet represent an outstanding aesthetic value – that intrinsic value, which usually distinguishes top-class masters, serves as a characteristic sign of them. Let us recall the most famous artists of our time (Kissin’s gift gives the right to such comparisons): their professional skill delights, touches in itself, as such, regardless of everything else. This cannot be said about Kisin yet. He has yet to rise to such heights. If, of course, we think about the world musical and performing Olympus.

And in general, the impression is that so far a lot of things in playing the piano have come quite easily to him. Maybe even too easy; hence the pluses and well-known minuses of his art. Today, first of all, what comes from his unique natural talent is noticed. And this is fine, of course, but only for the time being. In the future, something will definitely have to change. What? How? When? It all depends…

G. Tsypin, 1990