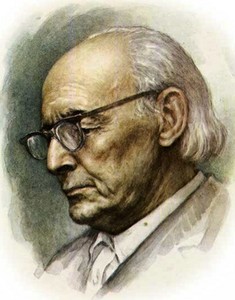

Dmitry Dmitrievich Shostakovich |

Dmitri Shostakovich

D. Shostakovich is a classic of music of the XNUMXth century. None of its great masters was so closely connected with the difficult fate of his native country, could not express the screaming contradictions of his time with such force and passion, evaluate it with a harsh moral judgment. It is in this complicity of the composer in the pain and troubles of his people that the main significance of his contribution to the history of music in the century of world wars and grandiose social upheavals lies, which mankind had not known before.

Shostakovich is by nature an artist of universal talent. There is not a single genre where he did not say his weighty word. He came into close contact with the kind of music that was sometimes arrogantly treated by serious musicians. He is the author of a number of songs picked up by the masses of people, and to this day his brilliant adaptations of popular and jazz music, which he was especially fond of at the time of the formation of the style – in the 20-30s, delight. But the main field of application of creative forces for him was the symphony. Not because other genres of serious music were completely alien to him – he was endowed with an unsurpassed talent as a truly theatrical composer, and work in cinematography provided him with the main means of subsistence. But the rude and unfair scolding inflicted in 1936 in the editorial of the Pravda newspaper under the heading “Muddle instead of music” discouraged him from engaging in the opera genre for a long time – the attempts made (the opera “Players” by N. Gogol) remained unfinished, and the plans did not pass into the stage of implementation.

Perhaps this is precisely what Shostakovich’s personality traits had an effect on – by nature he was not inclined to open forms of expressing protest, he easily yielded to stubborn nonentities due to his special intelligence, delicacy and defenselessness against rude arbitrariness. But this was only in life – in his art he was true to his creative principles and asserted them in the genre where he felt completely free. Therefore, the conceptual symphony became at the center of Shostakovich’s searches, where he could openly speak the truth about his time without compromise. However, he did not refuse to participate in artistic enterprises born under the pressure of strict requirements for art imposed by the command-administrative system, such as the film by M. Chiaureli “The Fall of Berlin”, where the unbridled praise of the greatness and wisdom of the “father of nations” reached the extreme limit. But participation in this kind of film monuments, or other, sometimes even talented works that distorted historical truth and created a myth pleasing to the political leadership, did not protect the artist from the brutal reprisal committed in 1948. The leading ideologist of the Stalinist regime, A. Zhdanov, repeated the rough attacks contained in an old article in the Pravda newspaper and accused the composer, along with other masters of Soviet music of that time, of adherence to anti-people formalism.

Subsequently, during the Khrushchev “thaw”, such charges were dropped and the composer’s outstanding works, the public performance of which was banned, found their way to the listener. But the drama of the composer’s personal fate, who survived a period of unrighteous persecution, left an indelible imprint on his personality and determined the direction of his creative quest, addressed to the moral problems of human existence on earth. This was and remains the main thing that distinguishes Shostakovich among the creators of music in the XNUMXth century.

His life path was not rich in events. After graduating from the Leningrad Conservatory with a brilliant debut – the magnificent First Symphony, he began the life of a professional composer, first in the city on the Neva, then during the Great Patriotic War in Moscow. His activity as a teacher at the conservatory was relatively brief – he left it against his will. But to this day, his students have preserved the memory of the great master, who played a decisive role in the formation of their creative individuality. Already in the First Symphony (1925), two properties of Shostakovich’s music are clearly perceptible. One of them was reflected in the formation of a new instrumental style with its inherent ease, ease of competition of concert instruments. Another manifested itself in a persistent desire to give music the highest meaningfulness, to reveal a deep concept of philosophical significance by means of the symphonic genre.

Many of the composer’s works that followed such a brilliant beginning reflected the restless atmosphere of the time, where the new style of the era was forged in the struggle of conflicting attitudes. So in the Second and Third Symphonies (“October” – 1927, “May Day” – 1929) Shostakovich paid tribute to the musical poster, they clearly showed the influence of the martial, propaganda art of the 20s. (It is no coincidence that the composer included in them choral fragments to poems by young poets A. Bezymensky and S. Kirsanov). At the same time, they also showed a vivid theatricality, which so captivated in the productions of E. Vakhtangov and Vs. Meyerhold. It was their performances that influenced the style of Shostakovich’s first opera The Nose (1928), based on Gogol’s famous story. From here comes not only sharp satire, parody, reaching the grotesque in the depiction of individual characters and the gullible, quickly panicking and quick to judge the crowd, but also that poignant intonation of “laughter through tears”, which helps us recognize a person even in such a vulgar and a deliberate nonentity, like Gogol’s major Kovalev.

Shostakovich’s style not only absorbed the influences emanating from the experience of world musical culture (here the most important for the composer were M. Mussorgsky, P. Tchaikovsky and G. Mahler), but also absorbed the sounds of the then musical life – that generally accessible culture of the “light” genre that dominated the minds of the masses. The composer’s attitude towards it is ambivalent – he sometimes exaggerates, parodies the characteristic turns of fashionable songs and dances, but at the same time ennobles them, raises them to the heights of real art. This attitude was especially pronounced in the early ballets The Golden Age (1930) and The Bolt (1931), in the First Piano Concerto (1933), where the solo trumpet becomes a worthy rival to the piano along with the orchestra, and later in the scherzo and the finale of the Sixth symphonies (1939). Brilliant virtuosity, impudent eccentrics are combined in this composition with heartfelt lyrics, amazing naturalness of the deployment of the “endless” melody in the first part of the symphony.

And finally, one cannot fail to mention the other side of the young composer’s creative activity – he worked hard and hard in the cinema, first as an illustrator for the demonstration of silent films, then as one of the creators of Soviet sound films. His song from the movie “Oncoming” (1932) gained nationwide popularity. At the same time, the influence of the “young muse” also affected the style, language, and compositional principles of his concerto-philharmonic compositions.

The desire to embody the most acute conflicts of the modern world with its grandiose upheavals and fierce clashes of opposing forces was especially reflected in the capital works of the master of the period of the 30s. An important step on this path was the opera Katerina Izmailova (1932), based on the plot of N. Leskov’s story Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. In the image of the main character, a complex internal struggle is revealed in the soul of a nature that is whole and richly gifted in its own way – under the yoke of the “lead abominations of life”, under the power of blind, unreasoning passion, she commits serious crimes, followed by cruel retribution.

However, the composer achieved the greatest success in the Fifth Symphony (1937), the most significant and fundamental achievement in the development of Soviet symphony in the 30s. (a turn to a new quality of style was outlined in the Fourth Symphony written earlier, but then not sounded – 1936). The strength of the Fifth Symphony lies in the fact that the experiences of its lyrical hero are revealed in the closest connection with the life of people and, more broadly, of all mankind on the eve of the greatest shock ever experienced by the peoples of the world – the Second World War. This determined the emphasized drama of the music, its inherent heightened expression – the lyrical hero does not become a passive contemplator in this symphony, he judges what is happening and what is to come with the highest moral court. In indifference to the fate of the world, the civic position of the artist, the humanistic orientation of his music, also affected. It can be felt in a number of other works belonging to the genres of chamber instrumental creativity, among which the Piano Quintet (1940) stands out.

During the Great Patriotic War, Shostakovich became one of the front ranks of artists – fighters against fascism. His Seventh (“Leningrad”) Symphony (1941) was perceived throughout the world as a living voice of a fighting people, who entered into a life-and-death struggle in the name of the right to exist, in defense of the highest human values. In this work, as in the later Eighth Symphony (1943), the antagonism of the two opposing camps found direct, immediate expression. Never before in the art of music have the forces of evil been depicted so vividly, never before has the dull mechanicalness of a busily working fascist “destruction machine” been exposed with such fury and passion. But the composer’s “military” symphonies (as well as in a number of his other works, for example, in the Piano Trio in memory of I. Sollertinsky – 1944) are just as vividly represented in the composer’s “war” symphonies, the spiritual beauty and richness of the inner world of a person suffering from the troubles of his time.

In the post-war years, the creative activity of Shostakovich unfolded with renewed vigor. As before, the leading line of his artistic searches was presented in monumental symphonic canvases. After the somewhat lightened Ninth (1945), a kind of intermezzo, which, however, was not without clear echoes of the recently ended war, the composer created the inspired Tenth Symphony (1953), which raised the theme of the tragic fate of the artist, the high measure of his responsibility in the modern world. However, the new was largely the fruit of the efforts of previous generations – that is why the composer was so attracted by the events of a turning point in Russian history. The revolution of 1905, marked by Bloody Sunday on January 9, comes to life in the monumental programmatic Eleventh Symphony (1957), and the achievements of the victorious 1917 inspired Shostakovich to create the Twelfth Symphony (1961).

Reflections on the meaning of history, on the significance of the deeds of its heroes, were also reflected in the one-part vocal-symphonic poem “The Execution of Stepan Razin” (1964), which is based on a fragment from E. Yevtushenko’s poem “The Bratsk Hydroelectric Power Station”. But the events of our time, caused by drastic changes in the life of the people and in their worldview, announced by the XX Congress of the CPSU, did not leave indifferent the great master of Soviet music – their living breath is palpable in the Thirteenth Symphony (1962), also written to the words of E. Yevtushenko. In the Fourteenth Symphony, the composer turned to the poems of poets of various times and peoples (F. G. Lorca, G. Apollinaire, W. Kuchelbecker, R. M. Rilke) – he was attracted by the theme of the transience of human life and the eternity of creations of true art, before which even sovereign death. The same theme formed the basis for the idea of a vocal-symphonic cycle based on poems by the great Italian artist Michelangelo Buonarroti (1974). And finally, in the last, Fifteenth Symphony (1971), the images of childhood come to life again, recreated before the gaze of a creator wise in life, who has come to know a truly immeasurable measure of human suffering.

For all the significance of the symphony in Shostakovich’s post-war work, it far from exhausts all the most significant that was created by the composer in the final thirty years of his life and creative path. He paid special attention to concert and chamber-instrumental genres. He created 2 violin concertos (1948 and 1967), two cello concertos (1959 and 1966), and the Second Piano Concerto (1957). The best works of this genre embody deep concepts of philosophical significance, comparable to those expressed with such impressive force in his symphonies. The sharpness of the collision of the spiritual and the unspiritual, the highest impulses of human genius and the aggressive onslaught of vulgarity, deliberate primitiveness is palpable in the Second Cello Concerto, where a simple, “street” motive is transformed beyond recognition, exposing its inhuman essence.

However, both in concerts and in chamber music, Shostakovich’s virtuosity is revealed in creating compositions that open up scope for free competition among musicians. Here the main genre that attracted the attention of the master was the traditional string quartet (there are as many written by the composer as symphonies – 15). Shostakovich’s quartets amaze with a variety of solutions from multi-part cycles (Eleventh – 1966) to single-movement compositions (Thirteenth – 1970). In a number of his chamber works (in the Eighth Quartet – 1960, in the Sonata for Viola and Piano – 1975), the composer returns to the music of his previous compositions, giving it a new sound.

Among the works of other genres, one can mention the monumental cycle of Preludes and Fugues for piano (1951), inspired by the Bach celebrations in Leipzig, the oratorio Song of the Forests (1949), where for the first time in Soviet music the theme of human responsibility for the preservation of the nature around him was raised. You can also name Ten Poems for choir a cappella (1951), the vocal cycle “From Jewish Folk Poetry” (1948), cycles on poems by poets Sasha Cherny (“Satires” – 1960), Marina Tsvetaeva (1973).

Work in the cinema continued in the post-war years – Shostakovich’s music for the films “The Gadfly” (based on the novel by E. Voynich – 1955), as well as for the adaptations of Shakespeare’s tragedies “Hamlet” (1964) and “King Lear” (1971) became widely known. ).

Shostakovich had a significant impact on the development of Soviet music. It was expressed not so much in the direct influence of the master’s style and artistic means characteristic of him, but in the desire for high content of music, its connection with the fundamental problems of human life on earth. Humanistic in its essence, truly artistic in form, Shostakovich’s work won worldwide recognition, became a clear expression of the new that the music of the Land of Soviets gave to the world.

M. Tarakanov