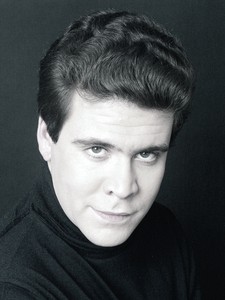

Alexis Weissenberg |

Alexis Weissenberg

One summer day in 1972, the Bulgaria Concert Hall was overcrowded. Sofia music lovers came to the concert of pianist Alexis Weissenberg. Both the artist and the audience of the Bulgarian capital were waiting for this day with special excitement and impatience, just like a mother is waiting for a meeting with her lost and newly found son. They listened to his game with bated breath, then they did not let him off the stage for more than half an hour, until this restrained and stern-looking man of a sporty appearance left the stage moved to tears, saying: “I am a Bulgarian. I loved and love only my dear Bulgaria. I will never forget this moment.”

Thus ended the nearly 30-year odyssey of the talented Bulgarian musician, an odyssey full of adventure and struggle.

The childhood of the future artist passed in Sofia. His mother, professional pianist Lilian Piha, began teaching him music at the age of 6. The outstanding composer and pianist Pancho Vladigerov soon became his mentor, who gave him an excellent school, and most importantly, the breadth of his musical outlook.

The first concerts of young Siggi – such was Weisenberg’s artistic name in his youth – were held in Sofia and Istanbul with success. Soon he attracted the attention of A. Cortot, D. Lipatti, L. Levy.

At the height of the war, the mother, fleeing the Nazis, managed to leave with him for the Middle East. Siggi gave concerts in Palestine (where he also studied with Professor L. Kestenberg), then in Egypt, Syria, South Africa, and finally came to the USA. The young man completes his education at the Juilliard School, in the class of O. Samarova-Stokowskaya, studies the music of Bach under the guidance of Wanda Landowskaya herself, quickly achieves resounding success. For several days in 1947, he became the winner of two competitions at once – the youth competition of the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Eighth Leventritt Competition, at that time the most significant in America. As a result – a triumphant debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra, a tour of eleven countries in Latin America, a solo concert at Carnegie Hall. Of the many rave reviews from the press, we cite one placed in the New York Telegram: “Weisenberg has all the technique necessary for a novice artist, the magical ability of phrasing, the gift of giving the melody melody and the lively breath of the song …”

Thus began the busy life of a typical itinerant virtuoso, who possessed strong technique and a rather mediocre repertoire, but which, however, had lasting success. But in 1957, Weisenberg suddenly slammed the lid of the piano and lapsed into silence. After settling in Paris, he stopped performing. “I felt,” he later admitted, “that I was gradually becoming a prisoner of routine, already known clichés from which it was necessary to escape. I had to concentrate and do introspection, work hard – read, study, “attack” the music of Bach, Bartok, Stravinsky, study philosophy, literature, weigh my options.

Voluntary expulsion from the stage continued – an almost unprecedented case – 10 years! In 1966, Weisenberg made his debut again with the orchestra conducted by G. Karayan. Many critics asked themselves the question – did the new Weissenberg appear before the public or not? And they answered: not new, but, no doubt, updated, reconsidered its methods and principles, enriched the repertoire, became more serious and responsible in its approach to art. And this brought him not only popularity, but also respect, although not unanimous recognition. Few pianists of our day so often come into the focus of public attention, but few cause such controversy, sometimes a hail of critical arrows. Some classify him as an artist of the highest class and put him on the level of Horowitz, others, recognizing his impeccable virtuosity, call it one-sided, prevailing over the musical side of the performance. Critic E. Croher recalled in connection with such disputes the words of Goethe: “This is the best sign that no one speaks of him indifferently.”

Indeed, there are no indifferent people at Weisenberg’s concerts. Here is how the French journalist Serge Lantz describes the impression that the pianist makes on the audience. Weissenberg takes the stage. Suddenly it begins to seem that he is very tall. The change in the appearance of the man we have just seen behind the scenes is striking: the face is as if carved from granite, the bow is restrained, the storming of the keyboard is lightning fast, the movements are verified. The charm is incredible! An exceptional demonstration of complete mastery of both his own personality and his listeners. Does he think about them when he plays? “No, I focus entirely on music,” the artist replies. Sitting at the instrument, Weisenberg suddenly becomes unreal, he seems to be fenced off from the outside world, embarking on a lonely journey through the ether of world music. But it is also true that the man in him takes precedence over the instrumentalist: the personality of the first takes on greater significance than the interpretive skill of the second, enriches and breathes life into a perfect performing technique. This is the main advantage of the pianist Weisenberg…”

And here is how the performer himself understands his vocation: “When a professional musician enters the stage, he must feel like a deity. This is necessary in order to subjugate the listeners and lead them in the desired direction, to liberate them from a priori ideas and clichés, to establish absolute dominion over them. Only then can he be called a true creator. The performer must be fully aware of his power over the public, but in order to draw from it not pride or claims, but the strength that will turn him into a true autocrat on the stage.

This self-portrait gives a fairly accurate idea of Weisenberg’s creative method, of his initial artistic positions. In fairness, we note that the results achieved by him are far from convincing everyone. Many critics deny him warmth, cordiality, spirituality, and, consequently, the real talent of an interpreter. What are, for example, such lines placed in the magazine “Musical America” in 1975: “Alexis Weissenberg, with all his obvious temperament and technical capabilities, lacks two important things – artistry and feeling” …

Nevertheless, the number of Weisenberg’s admirers, especially in France, Italy and Bulgaria, is constantly growing. And not by accident. Of course, not everything in the artist’s vast repertoire is equally successful (in Chopin, for example, sometimes there is a lack of romantic impulse, lyrical intimacy), but in the best interpretations he achieves high perfection; they invariably present the beating of thought, the synthesis of intellect and temperament, the rejection of any clichés, any routine – whether we are talking about Bach’s partitas or Variations on a theme by Goldberg, concertos by Mozart, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev, Brahms, Bartok. Liszt’s Sonata in B minor or Fog’s Carnival, Stravinsky’s Petrushka or Ravel’s Noble and Sentimental Waltzes and many, many other compositions.

Perhaps the Bulgarian critic S. Stoyanova defined Weisenberg’s place in the modern musical world most accurately: “The Weisenberg phenomenon requires something more than just an assessment. He requires the discovery of the characteristic, the specific, which makes him a Weissenberg. First of all, the starting point is the aesthetic method. Weisenberg aims at the most typical in the style of any composer, reveals first of all his most common features, something similar to the arithmetic mean. Consequently, he goes to the musical image in the shortest way, cleared of details … If we look for something characteristic of Weisenberg in expressive means, then it manifests itself in the field of movement, in activity, which determines their choice and degree of use. Therefore, in Weisenberg we will not find any deviations – neither in the direction of color, nor in any kind of psychologization, or anywhere else. He always plays logically, purposefully, decisively and effectively. Is it good or not? Everything depends on the goal. The popularization of musical values needs this type of pianist – this is indisputable.

Indeed, the merits of Weisenberg in the promotion of music, in attracting thousands of listeners to it, are undeniable. Every year he gives dozens of concerts not only in Paris, in large centers, but also in provincial towns, he especially willingly plays especially for young people, speaks on television, and studies with young pianists. And recently it turned out that the artist manages to “find out” time for the composition: his musical Fugue, staged in Paris, was an undeniable success. And, of course, Weisenberg now returns to his homeland every year, where he is greeted by thousands of enthusiastic admirers.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya., 1990