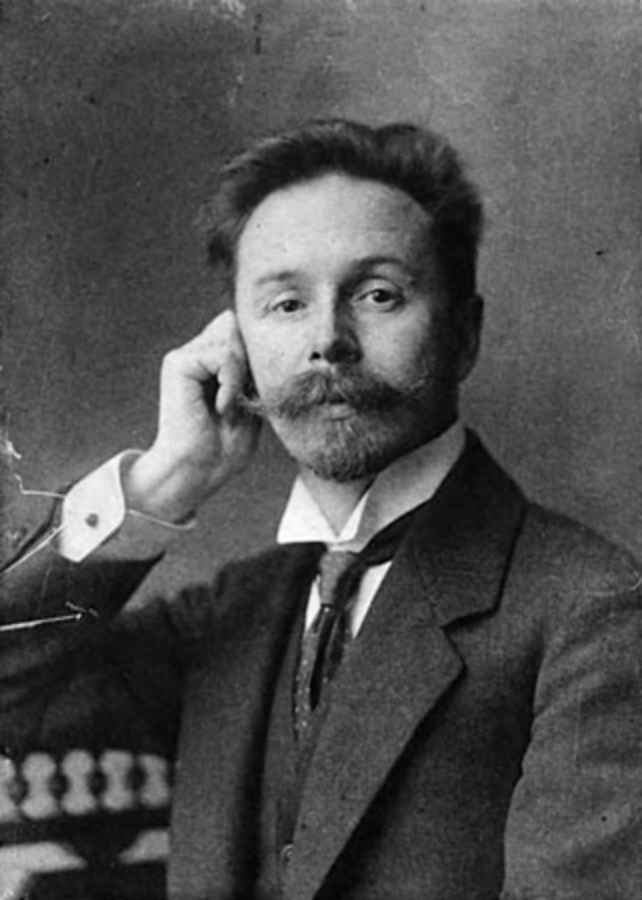

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (Alexander Scriabin).

Alexander Scriabin

Scriabin’s music is an unstoppable, deeply human desire for freedom, for joy, for enjoying life. … She continues to exist as a living witness to the best aspirations of her era, in which she was an “explosive”, exciting and restless element of culture. B. Asafiev

A. Scriabin entered Russian music in the late 1890s. and immediately declared himself as an exceptional, brightly gifted person. A bold innovator, “a brilliant seeker of new paths,” according to N. Myaskovsky, “with the help of a completely new, unprecedented language, he opens up such extraordinary … emotional prospects for us, such heights of spiritual enlightenment that grows in our eyes to a phenomenon of worldwide significance.” Scriabin’s innovation manifested itself both in the field of melody, harmony, texture, orchestration and in the specific interpretation of the cycle, and in the originality of designs and ideas, which to a large extent connected with the romantic aesthetics and poetics of Russian symbolism. Despite the short creative path, the composer created many works in the genres of symphonic and piano music. He wrote 3 symphonies, “The Poem of Ecstasy”, the poem “Prometheus” for orchestra, Concerto for Piano and Orchestra; 10 sonatas, poems, preludes, etudes and other compositions for pianoforte. Creativity Scriabin turned out to be consonant with the complex and turbulent era of the turn of the two centuries and the beginning of the new, XX century. Tension and fiery tone, titanic aspirations for freedom of spirit, for the ideals of goodness and light, for the universal brotherhood of people permeate the art of this musician-philosopher, bringing him closer to the best representatives of Russian culture.

Scriabin was born into an intelligent patriarchal family. The mother who died early (by the way, a talented pianist) was replaced by her aunt, Lyubov Alexandrovna Skryabina, who also became his first music teacher. My father served in the diplomatic sector. The love of music manifested itself in the little one. Sasha from an early age. However, according to family tradition, at the age of 10 he was sent to the cadet corps. Due to poor health, Scriabin was released from the painful military service, which made it possible to devote more time to music. Since the summer of 1882, regular piano lessons began (with G. Konyus, a well-known theorist, composer, pianist; later – with a professor at the conservatory N. Zverev) and composition (with S. Taneyev). In January 1888, the young Scriabin entered the Moscow Conservatory in the class of V. Safonov (piano) and S. Taneyev (counterpoint). After completing a counterpoint course with Taneyev, Scriabin moved to A. Arensky’s class of free composition, but their relationship did not work out. Scriabin brilliantly graduated from the conservatory as a pianist.

For a decade (1882-92) the composer composed many pieces of music, most of all for the piano. Among them are waltzes and mazurkas, preludes and etudes, nocturnes and sonatas, in which their own “Scriabin note” is already heard (although sometimes one can feel the influence of F. Chopin, whom the young Scriabin loved so much and, according to the memoirs of his contemporaries, perfectly performed). All of Scriabin’s performances as a pianist, whether at a student evening or in a friendly circle, and later on on the world’s largest stages, were held with constant success, he was able to commandively capture the attention of listeners from the very first sounds of the piano. After graduating from the conservatory, a new period began in the life and work of Scriabin (1892-1902). He embarks on an independent path as a composer-pianist. His time is filled with concert trips at home and abroad, composing music; his works began to be published by the publishing house of M. Belyaev (a wealthy timber merchant and philanthropist), who appreciated the genius of the young composer; relations with other musicians are expanding, for example, with the Belyaevsky Circle in St. Petersburg, which included N. Rimsky-Korsakov, A. Glazunov, A. Lyadov, and others; recognition is growing both in Russia and abroad. The trials associated with the disease of the “overplayed” right hand are left behind. Scriabin has the right to say: “Strong and mighty is he who has experienced despair and conquered it.” In the foreign press, he was called “an exceptional personality, an excellent composer and pianist, a great personality and philosopher; he is all impulse and sacred flame.” During these years, 12 studies and 47 preludes were composed; 2 pieces for the left hand, 3 sonatas; Concerto for piano and orchestra (1897), orchestral poem “Dreams”, 2 monumental symphonies with a clearly expressed philosophical and ethical concept, etc.

The years of creative flourishing (1903-08) coincided with a high social upsurge in Russia on the eve and implementation of the first Russian revolution. Most of these years, Scriabin lived in Switzerland, but he was keenly interested in the revolutionary events in his homeland and sympathized with the revolutionaries. He showed increasing interest in philosophy – he again turned to the ideas of the famous philosopher S. Trubetskoy, met G. Plekhanov in Switzerland (1906), studied the works of K. Marx, F. Engels, V. I. Lenin, Plekhanov. Although the worldviews of Scriabin and Plekhanov stood at different poles, the latter highly appreciated the personality of the composer. Leaving Russia for several years, Scriabin sought to free up more time for creativity, to escape from the Moscow situation (in 1898-1903, among other things, he taught at the Moscow Conservatory). The emotional experiences of these years were also associated with changes in his personal life (leaving his wife V. Isakovich, an excellent pianist and promoter of his music, and rapprochement with T. Schlozer, who played a far from unambiguous role in Scriabin’s life). Living mainly in Switzerland, Scriabin repeatedly traveled with concerts to Paris, Amsterdam, Brussels, Liege, and America. The performances were a huge success.

The tenseness of the social atmosphere in Russia could not but affect the sensitive artist. The Third Symphony (“The Divine Poem”, 1904), “The Poem of Ecstasy” (1907), the Fourth and Fifth Sonatas became the true creative heights; he also composed etudes, 5 poems for pianoforte (among them “Tragic” and “Satanic”), etc. Many of these compositions are close to the “Divine Poem” in terms of figurative structure. The 3 parts of the symphony (“Struggle”, “Pleasures”, “God’s Game”) are soldered together thanks to the leading theme of self-affirmation from the introduction. In accordance with the program, the symphony tells about the “development of the human spirit”, which, through doubts and struggle, overcoming the “joys of the sensual world” and “pantheism”, comes to “some kind of free activity – a divine game”. The continuous following of the parts, the application of the principles of leitmotivity and monothematism, the improvisational-fluid presentation, as it were, erase the boundaries of the symphonic cycle, bringing it closer to a grandiose one-part poem. The harmonic language is noticeably more complicated by the introduction of tart and sharp-sounding harmonies. The composition of the orchestra is significantly increased due to the strengthening of the groups of wind and percussion instruments. Along with this, individual solo instruments associated with a particular musical image stand out. Relying mainly on the traditions of late Romantic symphonism (F. Liszt, R. Wagner), as well as P. Tchaikovsky, Scriabin created at the same time a work that established him in Russian and world symphonic culture as an innovative composer.

The “Poem of Ecstasy” is a work of unprecedented boldness in design. It has a literary program, expressed in verse and similar in idea to the idea of the Third Symphony. As a hymn to the all-conquering will of man, the final words of the text sound:

And the universe resounded Joyful cry I am!

The abundance within the one-movement poem of themes-symbols – laconic expressive motifs, their diverse development (an important place here belongs to polyphonic devices), and finally, colorful orchestration with dazzlingly bright and festive culminations convey that state of mind, which Scriabin calls ecstasy. An important expressive role is played by a rich and colorful harmonic language, where complicated and sharply unstable harmonies already predominate.

With the return of Scriabin to his homeland in January 1909, the final period of his life and work begins. The composer focused his main attention on one goal – the creation of a grandiose work designed to change the world, to transform humanity. This is how a synthetic work appears – the poem “Prometheus” with the participation of a huge orchestra, a choir, a solo part of the piano, an organ, as well as lighting effects (the part of light is written out in the score). In St. Petersburg, “Prometheus” was first performed on March 9, 1911 under the direction of S. Koussevitzky with the participation of Scriabin himself as a pianist. Prometheus (or the Poem of Fire, as its author called it) is based on the ancient Greek myth of the titan Prometheus. The theme of the struggle and victory of man over the forces of evil and darkness, retreating before the radiance of fire, inspired Scriabin. Here he completely renews his harmonic language, deviating from the traditional tonal system. Many themes are involved in the intense symphonic development. “Prometheus is the active energy of the universe, the creative principle, it is fire, light, life, struggle, effort, thought,” Scriabin said about his Poem of Fire. Simultaneously with thinking about and composing Prometheus, the Sixth-Tenth Sonatas, the poem “To the Flame”, etc., were created for piano. Composer’s work, intense in all years, constant concert performances and travels associated with them (often for the purpose of providing for the family) gradually undermined his already fragile health.

Scriabin died suddenly from general blood poisoning. The news of his early death in the prime of life shocked everyone. All artistic Moscow saw him off on his last journey, many young students were present. “Alexander Nikolaevich Scriabin,” wrote Plekhanov, “was a son of his time. … Scriabin’s work was his time, expressed in sounds. But when the temporary, the transient finds its expression in the work of a great artist, it acquires permanent meaning and is done intransitive».

T. Ershova

- Scriabin – biographical sketch →

- Notes of Scriabin’s works for piano →

The main works of Scriabin

Symphonic

Piano Concerto in F sharp minor, Op. 20 (1896-1897). “Dreams”, in E minor, Op. 24 (1898). First Symphony, in E major, Op. 26 (1899-1900). Second Symphony, in C minor, Op. 29 (1901). Third Symphony (Divine Poem), in C minor, Op. 43 (1902-1904). Poem of Ecstasy, C major, Op. 54 (1904-1907). Prometheus (Poem of Fire), Op. 60 (1909-1910).

piano

10 sonatas: No. 1 in F minor, Op. 6 (1893); No. 2 (sonata-fantasy), in G-sharp minor, Op. 19 (1892-1897); No. 3 in F sharp minor, Op. 23 (1897-1898); No. 4, F sharp major, Op. 30 (1903); No. 5, Op. 53 (1907); No. 6, Op. 62 (1911-1912); No. 7, Op. 64 (1911-1912); No. 8, Op. 66 (1912-1913); No. 9, Op. 68 (1911-1913): No. 10, Op. 70 (1913).

91 prelude: op. 2 No. 2 (1889), Op. 9 No. 1 (for the left hand, 1894), 24 Preludes, Op. 11 (1888-1896), 6 preludes, Op. 13 (1895), 5 preludes, Op. 15 (1895-1896), 5 preludes, Op. 16 (1894-1895), 7 preludes, Op. 17 (1895-1896), Prelude in F-sharp Major (1896), 4 Preludes, Op. 22 (1897-1898), 2 preludes, Op. 27 (1900), 4 preludes, Op. 31 (1903), 4 preludes, Op. 33 (1903), 3 preludes, Op. 35 (1903), 4 preludes, Op. 37 (1903), 4 preludes, Op. 39 (1903), prelude, Op. 45 No. 3 (1905), 4 preludes, Op. 48 (1905), prelude, Op. 49 No. 2 (1905), prelude, Op. 51 No. 2 (1906), prelude, Op. 56 No. 1 (1908), prelude, Op. 59′ No. 2 (1910), 2 preludes, Op. 67 (1912-1913), 5 preludes, Op. 74 (1914).

26 studies: study, op. 2 No. 1 (1887), 12 studies, Op. 8 (1894-1895), 8 studies, Op. 42 (1903), study, Op. 49 No. 1 (1905), study, Op. 56 No. 4 (1908), 3 studies, Op. 65 (1912).

21 mazurkas: 10 Mazurkas, Op. 3 (1888-1890), 9 mazurkas, Op. 25 (1899), 2 mazurkas, Op. 40 (1903).

20 poems: 2 poems, Op. 32 (1903), Tragic Poem, Op. 34 (1903), The Satanic Poem, Op. 36 (1903), Poem, Op. 41 (1903), 2 poems, Op. 44 (1904-1905), Fanciful Poem, Op. 45 No. 2 (1905), “Inspired Poem”, Op. 51 No. 3 (1906), Poem, Op. 52 No. 1 (1907), “The Longing Poem”, Op. 52 No. 3 (1905), Poem, Op. 59 No. 1 (1910), Nocturne Poem, Op. 61 (1911-1912), 2 poems: “Mask”, “Strangeness”, Op. 63 (1912); 2 poems, op. 69 (1913), 2 poems, Op. 71 (1914); poem “To the Flame”, op. 72 (1914).

11 impromptu: impromptu in the form of a mazurki, soch. 2 No. 3 (1889), 2 impromptu in mazurki form, op. 7 (1891), 2 impromptu, op. 10 (1894), 2 impromptu, op. 12 (1895), 2 impromptu, op. 14 (1895).

3 nocturne: 2 nocturnes, Op. 5 (1890), nocturne, Op. 9 No. 2 for the left hand (1894).

3 dances: “Dance of Longing”, op. 51 No. 4 (1906), 2 dances: “Garlands”, “Gloomy Flames”, Op. 73 (1914).

2 waltzes: op. 1 (1885-1886), op. 38 (1903). “Like a Waltz” (“Quasi valse”), Op. 47 (1905).

2 Album leaves: op. 45 No. 1 (1905), Op. 58 (1910)

“Allegro Appassionato”, Op. 4 (1887-1894). Concert Allegro, Op. 18 (1895-1896). Fantasy, op. 28 (1900-1901). Polonaise, Op. 21 (1897-1898). Scherzo, op. 46 (1905). “Dreams”, op. 49 No. 3 (1905). “Fragility”, op. 51 No. 1 (1906). “Mystery”, op. 52 No. 2 (1907). “Irony”, “Nuances”, Op. 56 Nos. 2 and 3 (1908). “Desire”, “Weasel in the dance” – 2 pieces, Op. 57 (1908).